The cycle Régions d’être spans the unwieldy geographical remit of Slavs and Tatars – between the former Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China – while also serving as a prequel to the collective’s practice. Régions d’être is the collective’s term for an area that falls between the cracks of history and general knowledge: largely Muslim but not the Middle East, largely Russian speaking but not Russia, and having a complex relationship with the nation. Yet rather than representing a specific value, history or culture, this ‘region of being’ is as much an imagined, poetic geography as it is a real, political and historical geopolitics.

Slavs and Tatars is an internationally renowned art collective devoted to an area East of the former Berlin Wall and West of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia.

The collective’s practice is based on three activities: exhibitions, books and lecture-performances. In addition to launching a residency and mentorship program for young professionals from their region, Slavs and Tatars opened Pickle Bar, a slavic aperitivo bar-cum-project space in Berlin-Moabit, as well as an online merchandising store: MERCZbau.

Slavs and Tatars is represented by: Tanya Bonakdar (NYC), Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler (Berlin), Raster (Warsaw), The Third Line (Dubai) and Kalfayan (Athens).

Art and design students can apply for an Erasmus internship at Slavs and Tatars by sending an application to info@slavsandtatars.com

Press (selection)

Factory Rules

by Hannah Jacobi, Canvas, March-April, 2020

Wokół barów (i środku nich)

by Michał Grzegorzek, Szum, February 21, 2020

The Best and Worst Art in Central Europe in 2019

by Adam Mazur et al, Szum, January, 2020

Burlesque Biennial

by Jesse Seegers, Pin-Up, November, 2019

Review: ‘Pickle Politics’

by Polina Lasenko, Contemporary Media Arts Journal, November, 2019

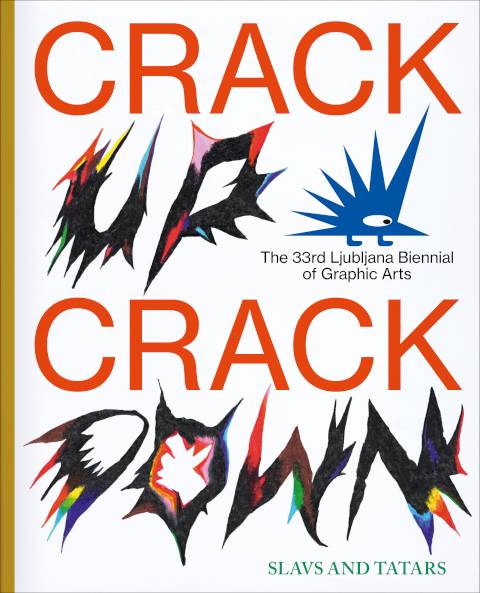

Review: ‘33rd Ljubljana Biennial’

by Franz Thalmair, Artforum, November, 2019

Pop Culture and Pickles: Inside the Berlin Studio of Slavs and Tatars

by Louise Benson, Elephant, October 25, 2019

33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts and The Powerful Language of Satire

by Emily McDermott, Frieze, September 6, 2019

The Art of Satire: Slavs and Tatars Interviewed

by Osman Can Yerebakan, Bomb, September 6, 2019

The 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts

by Tom Jeffreys, Art Agenda, July 19, 2019

Crack Up - Crack Down, 33rd Ljubljana Biennial

by Carlos Kong, Flash Art, July 15, 2019

58th Venice Biennale: May You Live In Interesting Times

by Mohammad Salemy, Ocula, May 24, 2019

Interview: 'Wo sich Harvard und Moskau mischen’

by Behrang Samsami, Politik und Kultur, April 2019

The New Alphabet — Opening Days

by Nick Currie, Art Agenda, January 31, 2019

Critics’ Picks

Artforum, December 2018

Die Botschaft der Gurke

Süddeutsche Zeitung, December 9, 2018

Sinn und Sinnlichkeit

Hannoversche Allgemeine, November 2018

Interview with Slavs and Tatars

The Gradient, September 2018

Review of Made in Dschermany

Art Asia Pacific, September 2018

Review of Made in Dschermany

Spike Art Quarterly, August 2018

Slavs and Tatars ar/ge Kunst / Bolzano

Flash Art, 23 August 2018

Essay: ‘Reverse Joy’

Diaphanes, 10 April 2018

Interview

by Peter Backhof, DLF Radio, 31 January 2018

Conversation with Slavs and Tatars

by Ráhel Anna Molnár, exindex, 25 January 2018

Looking forward: Europe

by Slavs and Tatars, frieze, 10 January 2018

Usta Usta - Slavs and Tatars

by Anna Zakrzewska, TV Polonia , 2017

Aus Freude am Teilen

by Johannes Wendland, Handelsblatt, 12 November 2017

Interview

by Fanny Magyar, artportal, 8 November 2017

Threads Left Dangling, veiled in ink

by Max L. Feldman, Artforum, 24 October 2017

Doing the splits

frieze, 15 October 2017

Review: ‘Mouth to Mouth’ at CAC

by Maija Rudowska, Selections, 12 October 2017

Review: ‘Mouth to Mouth’ at SALT, Istanbul

by Naz Cuguoğlu, Asia Art Pacific, 105, 2017

Interview: ‘Relationships’

by John Clifford Burns, Kinfolk Vol. 24, June 2017

Review: ‘Slavs and Tatars, Usta Usta’

by Piotr Policht, Szum, No. 16, 2017

Metaphysical splits

by Adriana Bidlaru, Revista Arta, 26 March 2017

Odnalezione w Tłumaczeniu

by Piotr Kosiewski, Tygodnik Powszechny, 13 February 2017

Slavs and Tatars: Mouth to Mouth

by Tausif Noor, Art Radar, 11 January 2017

Tłumaczenie Światów

by B. Deptuła and P. Drabarczyk, Harper’s Bazaar Polska, January 2017

Slavs and Tatars

by Gregor Volk, Art in America, 29 December 2016

Review: ‘Afteur Pasteur’

by Owen Duffy, ArtReview, December 2016

Slavs and Tatars Afteur Pasteur

by Ann McCoy, The Brooklyn Rail, 1 November 2016

With Satire, Whimsy, and Fermented Milk

by Osman Can Yerebakan, Hyperallergic, 14 October 2016

Slavs and Tatars’ Mirror for Princes

by Anthony Hawley, The Brooklyn Rail, 6 April 2016

Review: ‘Towarszystwo Szubrawców’

by Bean Gilsdorf, Artforum, 14 June 2016

Naughty Nasals and Monobrow Manifestos

by Dina Akhmadeeva, Canvas, May/June 2016

Slavs and Tatars

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad, artpress 2, No 40, 2016

Men are from Murmansk, Women are from Vilnius

by Molly Glentzer, Houston Chronicle, 22 January 2016

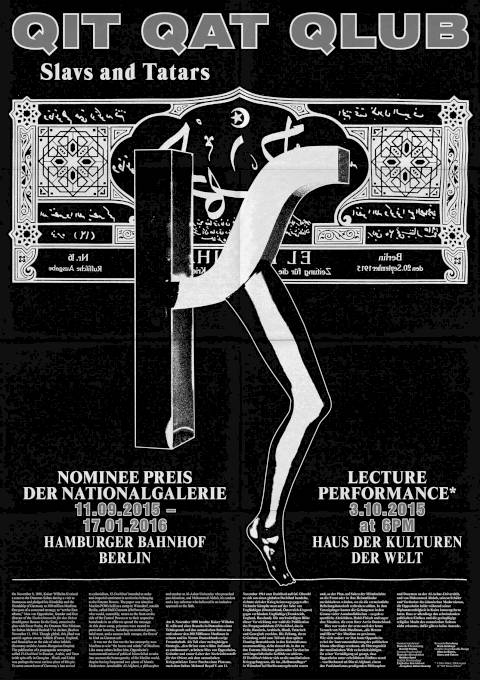

Germany’s Leading Art Prize Sets a Museum in Motion

by Gretta Louw, Hyperallergic, 11 January 2016

Lost in Translation

by Thea Ballard, Modern Painters, 15 January 2016

Best of 2015

Hyperallergic, 17 December 2015

The lands time forgot

by Miriam Cosic, The Australian, 19 November 2015

Alphabet und Imperium

by Slavs and Tatars, frieze d/e, No 22, 2015

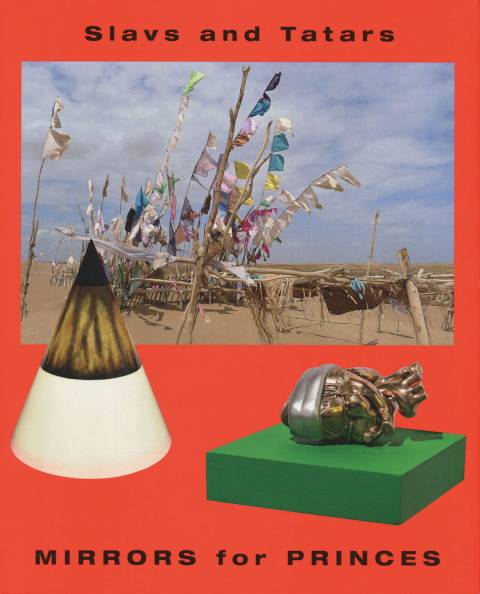

Preview: ‘Mirrors for Princes’

by Nicholas Forrest, BlouinArtInfo, 30 October 2015

Review: ‘Dschinn and Dschuice’

by Ana Ofak, Art Agenda, 9 November 2015

Review: ‘Mirrors for Princes’

by Kevin Jones, Flash Art, 9 November 2015

New Yarns

by Kirsty Bell, Tate Etc, issue 33, 2015

Wall to Wall

by Dina Akhmedeeva, Calvert Journal, 19 March 2015

Slavs and Tatars encourages art you’re allowed to sit on

by Nick Leech, The National, 26 February 2015

Review: ‘Language Arts’

by Kevin Jones, Art Asia Pacific, Nov/Dec 2014

Review: ‘Mirrors for Princes’

by Myriam Ben Salah, artpress, November 2014

Interview with Slavs and Tatars

by Anna Tolstova, Коммерсантъ, 27 June 2014

The New Manifestos

by Ian Wallace, artspace, 17 May 2014

Review: ‘Language Arts’

by Anna Seaman, The National, 1 April 2014

Interview with Slavs and Tatars

by Deena Chalabi, Issues, 2014

The languages of art, politics and melons

by Jim Quilty, The Daily Star, 28 March 2014

Slavs and Tatars, l’art des antipodes

by Roxana Azimi, Le Monde, 26 March 2014

Cтрана которой нет

by Sergey Guskov, Harper’s Bazaar Art, April 2014

A Conversation with Slavs and Tatars

by James Scarborough, Huffington Post, 11 March 2014

Syncretic Cartographies

by Stephanie Bailey, Yishu, Vol 13, Nº 1, 2014

On Aggregators

by David Joseilt, October, Nº 146, Fall, 2013

Tire Ta Langue

by Bernard Blistène, France Culture, 17 February 2013

Review: ‘Long Legged Linguistics’

by H.G. Masters, Art Asia Pacific, 2013

Peripheral Vision

by Kimberley Bradley, artsy.net, 2013

Q&A Art Space Pythagorion

by Gesine Borcherdt, artinfo.com, 2013

Panslawizm – tak!

by Adriana Prodeus, Newsweek, issue 27, 2013

Nie Chcemy Być Nowocześni

by Iwona Kurz, dwutygodnik.pl, issue 110, 2013

Lange Beine – bewegliche Zungen

by Samuel Herzog, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 27 August 2013

Children of Marx and Kumis

by Joel Regev and Masha Shtutman, colta.ru, 2013

Interview

by Franz Thalmair, l'Officiel Art, Nº 6., 2013

Review of ‘Beyonsense’

by Media Farzin, Bidoun, issue 28, 2013

Review of ‘Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz’, Critics’ Picks

by Steve Kado, Artforum, 2013

Reverse Optimism

by Fionn Meade, Modern Painters, March 2013

Slavs and Tatars

by Jesi Khadivi, Harper’s Bazaar Art Arabia, Nov-Dec 2012

Print/Out: 20 Years in Print

(ed.) Christophe Chérix, MoMA, 2012

Caucasian Bazaar

by Iwo Zmyślony, dwutygodnik.pl, issue 40, 2012

For the Birds

by Kevin Kinsella, BombBlog, 5 November 2012

Beyond Nonsense: What Slavs and Tatars Make

by Anders Kreuger, Afterall, Fall 2012

Slavs and Tatars Bring Eurasian Transreason to MoMA

by Austin Considine, Art in America, 16 October 2012

Political He Says

by Jon Leon, Spike, no 33, Autumn 2012

Представители трещины

by Igor Gulin, Kommersant, 31 August 2012

Interview ‘Q&A’

Frieze, May 2012

Gauging the Power of the Print

by Ken Johnson, The New York Times, 16 February 2012

Five Plus One

by H.G. Masters, Asia Art Pacific, Almanac 2011, 2012

A Daring Eastern Publication

by Christopher Lord, The National, 21 December 2011

I decided not to save the world

by J.J. Charlesworth, TimeOut, 17 November 2011

Slavs and Tatars: Collective Eclecticism

by H.G. Masters, Asia Art Pacific, issue 75, 2011

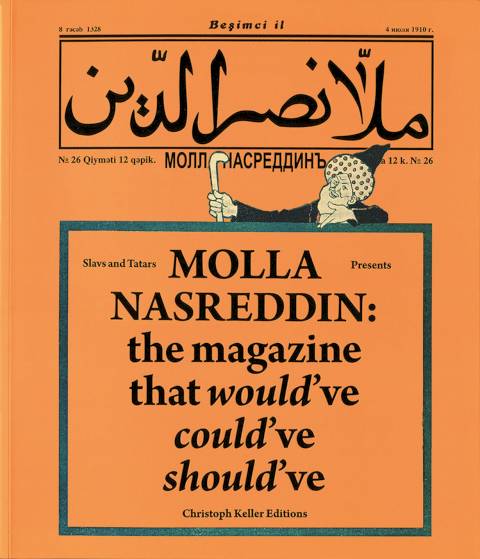

Molla Nasreddin review

by Alexander Provan, Bidoun, issue 25, 2011

The Last of the Eurasianists

by Carson Chan, Kaleidoscope, issue 11, 2011

Molla Nasreddin review

by David Shariatmadari, The Guardian, 24 June 2011

Molla Nasreddin redux

by Peter Gordon, Asian Review of Books, 2011

Müslüman, laik, demokrat devrimciler

by Nigar Hacizade, Radikal, 30 May 2011

The magazine that almost changed the world

by Elizabeth Minkel, The New Yorker, 26 May 2011

Der “Nebelspalter” der muslimischen Welt

by Daniel Morgenthaler, Basler Zeitung, 13 April 2011

Future Greats

by Adam Budak, Art Review, March 2011

Group Think

by Nicholas Cullinan, Artforum, February 2011

Interview with Slavs and Tatars

by Federica Bueti, artslant.com, August 2010

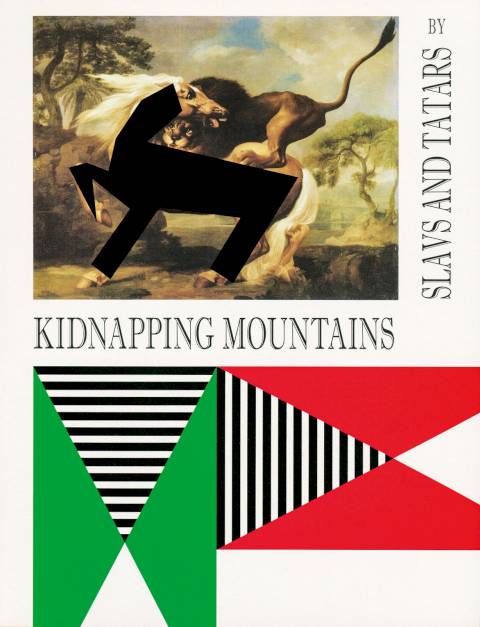

Short takes: Kidnapping Mountains

Bidoun, issue 20, 2010

Visionaire No. 57

Visionaire No. 57, 2010

Kidnapping Mountains

by Jasmine De Bruycker, Klara.be, 13 May 2009

The Expatriate

by Shaun Walker, Fantastic Man, issue 9, 2009

I Often Dream of Slavs

by Negar Azimi, Bidoun, issue 16, 2009

Novi Moskvich

by Anna Dyulgerova, Harper’s Bazaar, September 2008

Rebuilding the Pantheon

by Ingrid Chu, Fillip, issue 8, 2008

Wall to Wall

by Alison Cool, Style.com, 8 April 2008

Art between Covers

by Holland Cotter, New York Times, 29 September 2007

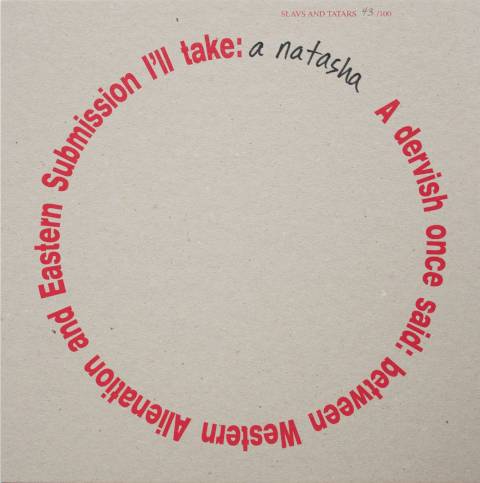

Tranny Tease pour Marcel

First appearing in 2009 and one of the rare series which has continued throughout the duration of the collective’s practice, Slavs and Tatars’ iconic series Tranny Tease (pour Marcel) explore the alphabet politics behind the phenomenon of transliteration, particularly poignant in a region where millions of inhabitants have experienced if not three then two distinct changes of script in the past century. Each vacuum-formed panel uses the ‘wrong’ script for the language of the text.

Samovar

Taking the form of an oversized inflatable water boiler, teapot and serving tray lodged into the side of the Hayward Gallery, the sculpture is titled after the eponymous tea brewer commonly found across Central Asia.

A Russian invention of the mid-18th century, samovars are used today across Eastern Europe, the Middle East and some parts of Asia, in both domestic and communal settings.

Although humorously enlarged like a mascot or parade float, Slavs and Tatars’ installation uses the samovar as an emblem to recount the ways in which the history of tea is intertwined with cross-cultural exchange and colonialism.

By creating a monumental symbol of a celebrated and long-established tea culture, the artwork questions the role of tea in British history, tradition and popular culture.

Hi Brow!

A pocket mirror doubles as a chair in Hi, Brow!: a social sculpture and performance providing visitors the chance to receive a monobrow courtesy of a beautician.

Noblesse Oblige

Slavs and Tatars’ work often mixes registers of high and low, high-brow ideologies and low-brow media (pickles to balloons). In that vein, roasted sunflower seeds are a staple snack, shared across the Slavic-Turkic peoples from Eastern Europe to Central Asia. Like the wheat of Wheat Mollah, the sunflower seed becomes a symbol of proletariat or rather, its 21st century sucessor, the précariat.

Hamdami

Characteristic of the artists’ interest in coincidentia oppositorum (the coincidence of opposites) equally as a strategy as subject matter, Hamdami explores the conspiration of the sensual and spiritual.

RiverBed

The takht (bed, or what we call a ‘RiverBed’ in honour of its ideal location by a source of water), the vernacular structure found at teahouses, roadside kiosks, shrines, entrances to mosques and restaurants across Iran and Central Asia, accommodates a group of roughly four or five people without the unfortunate and unspoken delineation of individual space dictated by the chair. Friends, families, and colleagues sit, smoke shisha, sip tea, eat lunch, take naps, and create – however momentarily – a sense of public space, all the more remarkable in countries where public space is circumscribed, such as Iran.

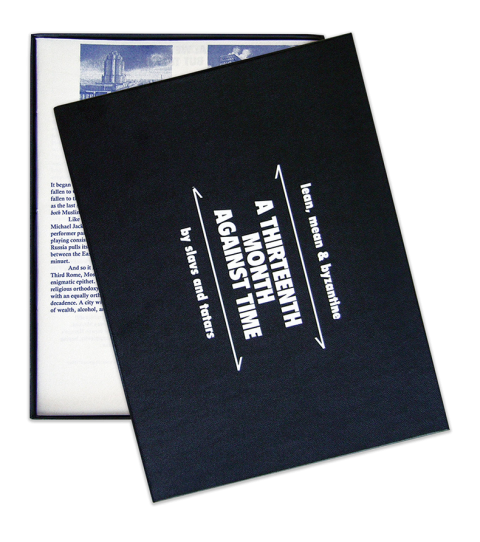

Reading Rooms

The book is central to Slavs and Tatars’ practice. In addition to an extensive publishing practice, the artists create spaces, sculptures, lecture-performances, installations and audio works all of which ostensibly bring us back to the book. For most of its history, though, reading has been a collective practice, not a private one. You could say the private or individual book as such is really only about 150 years old. Slavs and Tatars are committed to re-activating the idea of collective reading: not necessarily in the lteral sense of reading together, but rather in an attempt to create a multiple subjectivity, to read as a body of multiples. Above is a selection of various reading spaces within their exhibitions.

Kitab Kebab

A traditional kebab skewer pierces through a selection of Slavs and Tatars’ books, suggesting not only an analytical but also an affective and digestive relationship to text. The mashed-up reading list proposes a lateral or transversal approach to knowledge, an attempt to combine the depth of the more traditionally-inclined vertical forms of knowledge with the range of the horizontal.

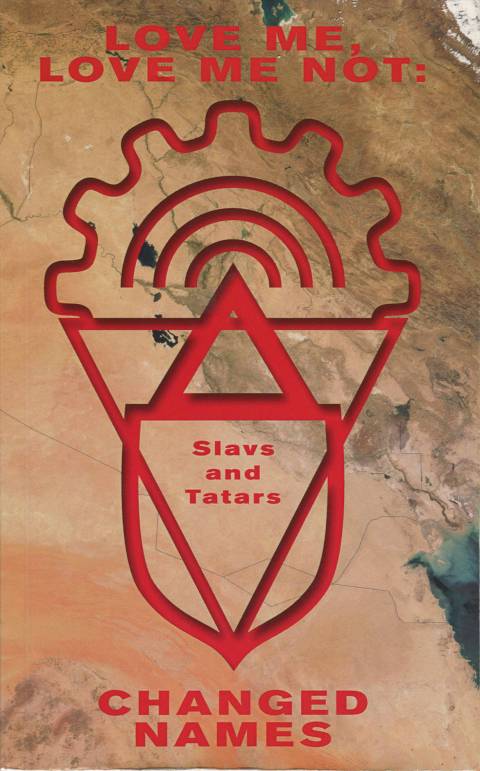

Love Me, Love Me Not

A genealogy of a given city’s name changes, the result of rising or falling empires, states, and/or populations. Some cities divulge a resolutely Asian or Muslim heritage, so often forgotten in some citizens’ quest, at all costs, for a European, Christian identity. Others vacillate almost painfully, and others with numbing repetition, entire metropolises caught like children in the spiteful back and forth of a custody battle. Like much of Slavs and Tatars’ work, Love Me Love Me Not was first conceived as a book, a compilation of 150 such city names.

PrayWay

A collision of the sacred and the profane – the rahlé, the traditional book stand used for holy books, and the takht (or river-bed), vernacular seating areas used in tea-salons – PrayWay is part installation, part sculpture, part seating area, and all polemical platform.

Molla Nasreddin the antimodern

Often depicted riding backwards on his donkey, Nasreddin is a transnational folk figure found in different guises and under various names from Morocco to Croatia, Sudan to China. Using first-degree humour to question issues of morality and ethics, he has become a retro-active mascot of sorts for Slavs and Tatars. In Molla Nasreddin the antimodern the artists have given the old dervish a bounce to his step and made extra room for a sidekick. Children hold on tight to Hodja’s portly belly as this Sufi super-hero faces the past but trots into the future, cutting a profile of an anti-modern figure.

Nations

Whether it’s gender politics as geo-politics, migrant labor, or jadidism, to name a few, Nations employ bawdy humour and deliberate one-liners to deliver ice-breakers of unassuming density.

Régions d’être

“Despite their specifically-defined geographical remit, and commitment to this particular region, in some ways ‘Eurasia’ (the continental span that includes Asia, the Middle East, and Europe) is a foil: allowing viewers and audiences to consider their own relationships to more general questions of belonging, foreignness, citizenry, and to the multiple subjectivities that dwell, rightfully yet often with conflict, within any single place. This characteristic attention and care, deployed with humour, is tied to the collective’s transregional perspective: their understanding that any single place or person is in fact made up of many, and that the specific bleeds into the general. If the region of Eurasia is a deliberately broad net to cast, then without any instrumentalization, Slavs and Tatars find, accumulate, and re-present bodies of knowledge and material histories that can seem (to some) minute, niche, and arcane. This characteristic straddling of materiality and ideology, history and belief, the particular and the absolute” is a tension maintained within the jungle-gym of Régions d’être.

Excerpt from Slavs and Tatars, ed. by Pablo Larios, published by König Books, 2017

When in Rome

A deliberate slippage of terminology allows for a moment that is equally commemorative and confused. Coins are offered, not for beggars, but for believers as is often found strewn across icons of Orthodox Christianity. If modernity is the totalizing project of the 20th century, one that doesn’t allow for failure, one where expediency trumps reflection, perhaps Roma offer the possibility of escape, from the tyranny of the past and present.

Idź na Wschód!

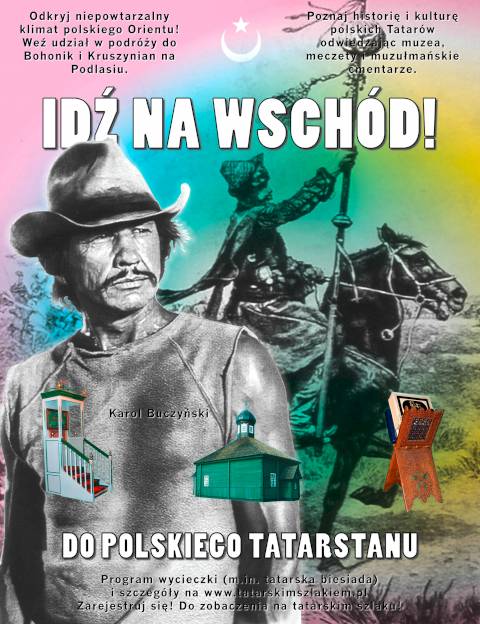

In 2009, Slavs and Tatars organized a day trip to Bohoniki and Kruszyniany, two Tatar villages in Poland, located near the Byelorussian border, which offer a cosmopolitan understanding of Polish identity and an ideal model of progressive Islam via the creolized vernacular architecture of the wooden mosques and the liberal relationship between men and women. In the Wola district of Warsaw, a billboard inviting people to ‘Go East’ featured Charles Bronson, né Karol Buczynski, of Once Upon a Time in the West fame, whose cheekbones and eyes were often mistaken for Mexican or Native American but were in fact a remnant of his Lipka Tatar heritage.

Histoire du Monde Slave et Tatar

Histoire du Monde Slave et Tatar proposes a revision of Louis-Henri Fournet’s famous Tableau Synoptique de l’Histoire du Monde, literally a visual diagram of the past 5000 years (or fifty centuries) of world history, to mark those regions falling within the artists’ geographic remit.

A celebration of complexity in the Caucasus, this cycle investigates the linguistic, social and political phenomena of a region at the site of historical crossroads between Ottoman, Persian and Russian empires.

To Mountain Minorities

The original Georgian expression ‘Chven Sakartvelos Gaumardjos’ is roughly translated as ‘Long Live Georgia!’ or ‘Vive la Georgie!’. By changing a single letter, however, the ‘a’ of ‘Sakartvelos’ to a ‘u’ to make ‘Sakurtvelos’, the phrase becomes ‘Long Live Kurdistan!’ and the unresolved geopolitical identity of one mountain peoples is replaced with that of another.

Mountains of Wit

Горе от Ума (Gore ot Uma, meaning ‘woe from wit’) is a famous 19th century play about Moscow manners by Aleksander Griboyedov, a close friend of Pushkin’s and diplomat to the Tsar in the Caucasus. By changing the ‘e’ in the original Russian title to an ‘Ы’, a quintessentially Russian letter, the title becomes Mountains of Wit, and the urban premise of the original work is hijacked by a Caucasian setting equally imaginative and apposite, one which played an influential role in Griboyedov’s life and death.

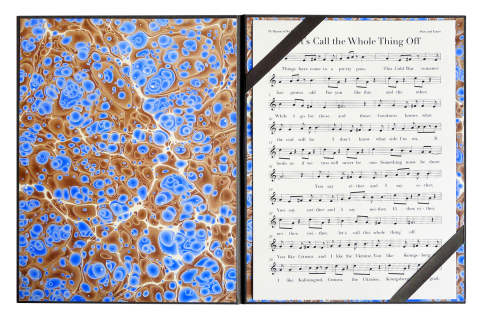

Hymns of No Resistance

Hymns of No Resistance features classic and cult pop songs revised to address issues of territorial dispute, language, and geopolitics within greater Eurasia. An adaptation of Michael Sembello’s Flashdance track ‘She’s a Maniac’ becomes ‘She’s Armenian’, replacing the struggles of an aspiring dancer with those of a diaspora Armenian. Meanwhile, ‘Young Kurds’ – a retelling of Rod Stewart’s ‘Young Turks’ – tells the story of Sherko and Shirin, a Kurdish couple on the run. ‘Stuck in Ossetia with You’ (originally ‘Stuck in the Middle with You’ by Stealers Wheel) looks at the 2008 Russo-Georgian war.

Letter to Abriskil aka Amiran aka Prometheus

For the West, it was Prometheus who stole fire from Zeus and gave it to the mortals, and whose punishment was to be chained to a mountain (which happened to be in the Caucasus), with his liver eternally torn out by the beak of an eagle.

For the Ossetians, it was Amiran aka Abriskil who, according to legend, got into a rock-throwing match with Jesus. After an enormous boulder hurled past Jesus and lodged itself deep into a mountain, Jesus challenged Amiran to unearth the rock. Amiran did not succeed, and as punishment was chained to the peak of Mt. Kazbek. Amiran was a repeat offender, to use the revanchist legal lingo of his foe’s fanboys (i.e. Republicans): the son of a sorcerer, he singled out Christians for punishment. To this day, it is said that Amiran's despair and struggle to break free of his chains is what causes the avalanches and earthquakes in the greater region.

Kidnapping Mountains (Over-Here)

Given the density of different ethnic groups and languages in the Caucasus, sometimes from disparate language families, Kidnap Over-Here argues for a pre-modern understanding of identity, one which is spatially-inflected. For example, the Georgians living west of the Likhi mountain range, considered by some to be the natural border between Europe and Asia, refer to themselves as the “over-here’s” and to those living on the east side of the range as the “over-there’s”.

Dig The Booty

Dig the Booty features a transliteration of an aphorism across the Latin, Cyrillic and and Perso-Arabic scripts in homage to the vicissitudes of the Azeri alphabet which changed 3 times over the past century: from Arabic to Latin in 1929, from Latin to Cyrillic in 1939, only to go back to Latin in 1991.

The cycle began with a study of unexpected points of commonality between the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and Poland’s Solidarność movement of the 1980s, events that coincided with major geopolitical shifts in the twentieth century, resulting in the emergence of revolutionary Islam on the one hand, and the fall of communism on the other. The points of convergence between Poland and Iran’s respective quests for self-determination extend to 17th century Sarmatism, an exodus of Polish refugees to Iran during World War II, and the intermingling of faith and citizen diplomacy.

Communion

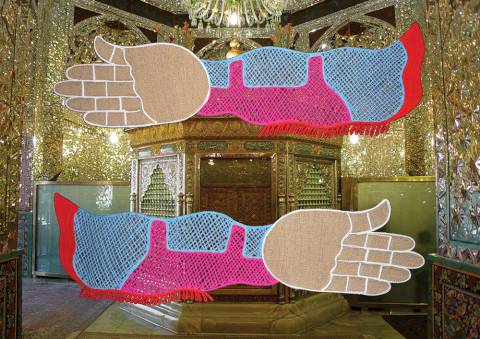

A series of reverse-glass paintings exploring the overlaps between Catholic and Sh’ia theology and iconography.

Inrising

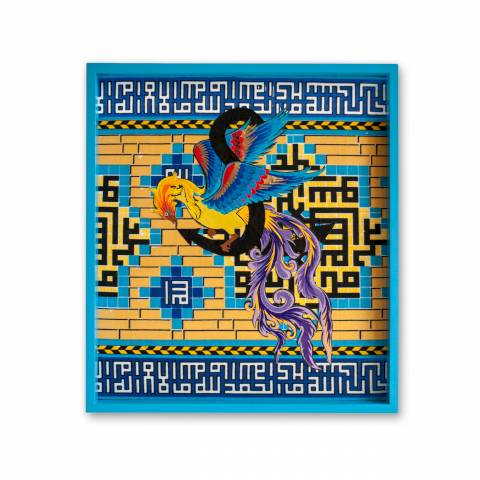

Just as the anti-communist Solidarność Walcząca used the royal eagle, banned from official Polish insignia during communist rule, as an act of defiance to martial law, Inrising looks to the simorgh, the mythical Persian bird and Sufi symbol as a sign of solidarity, albeit in a less socio-economic and more mystical understanding of the term. The simorgh figures heavily in literary works such as Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and Attar’s Conference of the Birds: here the literary trope has been translated into a Polish craft technique of intricate paper cut-outs known as wycinanki.

Samizabt

Featuring a translation of Czesław Miłosz’s ‘Który skrzywdziłeś’ (You Who Wronged) into Persian, the sound work Samizabt (2013) speaks to the role of poetry as a form of political resistance. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from tsarist Russia to communist Poland, poets were considered a threat to the state, a stark contrast to their esoteric if not marginal role in Western nations. Following protests in Iran over the results of the 2009 presidential elections, works of Polish authors hitherto untranslated began to pop up in Tehran’s bookstores in Persian. Whether it was the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, philosopher Leszek Kołakowski, or poet Wisława Szymborska, the new crop of a particular nation’s literature makes a convincing case for early twenty-first century Iran to look to Poland’s late twentieth-century struggle with communism. Solidarność’s turn to religion and faith for its progressive potential and effective means of resistance, especially in the face of the creeping secular materialism left unchecked after the fall of the Iron Curtain, resonated with an opposition movement in Iran trying to triangulate between political Islam and the desire for a truly representative government.

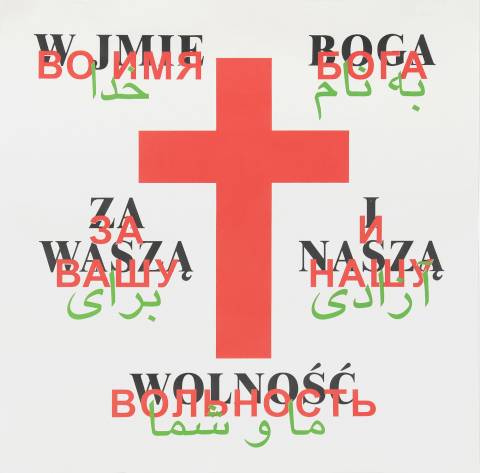

In the Name of God

An unofficial motto of Poland, ‘W imię Boga za Naszą i Waszą Wolność’ (In the Name of God, For Your Freedom and Ours) has been appropriated by peoples all around the world in their struggles for self-determination. Featuring both Russian and Polish in its original iteration, the poster is a complex nod to the fate binding two countries whose history has been contentious to say the least. By translating the original into Persian and reinstating the Russian, In the Name of God addresses the transnational, if not transcendental, nature of this phrase, aiming to rescue it from the jaws of parochial or imperial instrumentalization.

Mystical Protest

Mystical Protest looks at the numinous, or the holy, as a potential agent for change in the concrete, material world. Muharram is the first month of the Islamic calendar and the second holiest month, following Ramadan. Each year, during the month of Muharram, Shi’ites re-enact various rituals and rites surrounding the death of Hussein Ibn Ali, the Prophet’s Mohammed’s grandson. A text reading “It is of utmost importance that we repeat our mistakes as a reminder to future generations of the depths of our stupidity” offers a defeatist admonishment to revolutionary calls for change.

Solidarność Pająk Studies

Originally a pagan tradition, the pająk (lit. ‘spider’ in Polish) was traditionally hung from the homes of rural Poles to celebrate the harvest and to bless the upcoming year of crops. Crafted according to local customs, they are often made with found, ephemeral materials. Slavs and Tatars revisit the pająk as a testimony to the painstaking diligence and delicate nature of compromise crucial to the Polish precedent of civil disobedience. Solidarność Pająk study 1-9 creolizes the pająk by integrating elements or motifs of Iranian Shi’a culture into an originally pantheist then Catholic-Polish one. In one, flowers are replaced with the wool bangles habitually adorning Persian carpets; in another, the reeds form the outline of the Allah crest of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Like the mirror mosaics of Resist Resisting God, the pająk is an example of craft as a vehicle for revolutionary critique and ideology.

Study for Sarmat Surfaces

One of the more surprising convergences in our studies of Iran and Poland has been the visual culture and craft traditions of their dominant faiths: Shi’a Islam and Catholicism, respectively. These range from passion plays and re-enactions of the Stations of the Cross to Ta’zieh, Carnival floats, Muharram alam, as well as banners and reverse-glass painting. Upending traditional notions of Renaissance perspective, painting behind glass requires beginning with the outermost layer, say the eyes, and moving inwards towards the background.

In Friendship of Nations, we often turned to crafts for their ability to decouple innovation from individuality. When push comes to shove, unlike the arts, crafts tend to opt for repetition over difference: an apprentice calligrapher for example, must spend some ten years copying his or her mentor before daring to attempt a flourish of their own. Such an approach allows us to consider innovation not as a series of ruptures or patricides, as the avant-garde would have us believe, but rather as a continuous process. Repetition – be it the mantra of a zikr or the stitching of a needlework piece – revolves around a certain genealogical transparency so engrossing that it verges on transubstantiation; one must not just reveal one’s sources but become them.

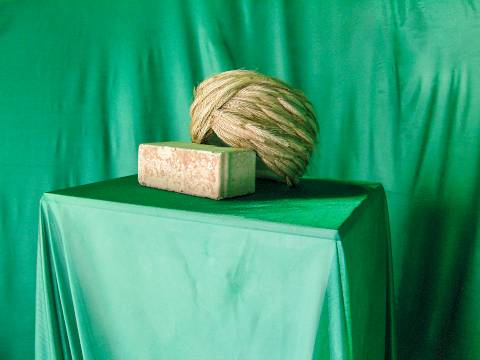

Wheat Mollah

A nod to the often-overlooked leftist origins of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. From the basic building block of food – bread – to the ideological stand-in for socialism, it could be argued that wheat emits a sacred, almost atavistic aura, and not just in Slavic countries. Established in 1925, Bank Sepah, Iran’s first bank, today sports a logo combining the stylized lettering for ‘Allah’, as found on the flag of the Islamic Republic, surrounded by a wreath of tulips on the left and a stalk of wheat on the right. This inadvertent tribute to the crest of the USSR, whose hammer and sickle are surrounded by two stalks of wheat, would make Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, the inheritors of the Army Pension Fund at the origin of Bank Sepah, drop their collective jaws. Add to wheat's impressive arsenal a talismanic quality: how else to explain that wheat has that rare ability to combine the seemingly incommensurate: communism and political Islam?

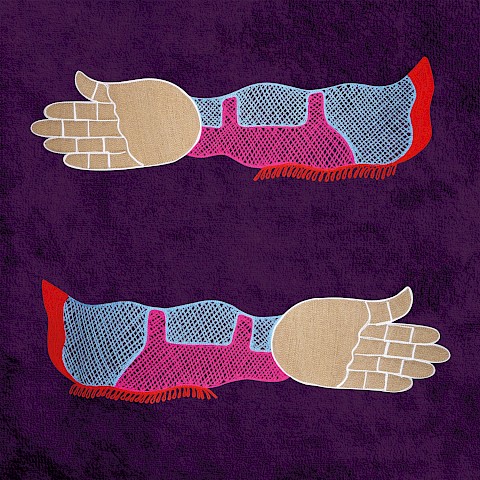

Friendship of Nations

Made accordingly by Polish seamstresses or Iranian tailors, the Friendship of Nations banners comprise the main body of work of the eponymous cycle. Creolizing best-practices from the Solidarność movement and the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the banners also speak to the unlikely points of resonance between craft traditions of the Catholic faith and Shi'a Islam.

Pre-Write Your History

On the occasion of the exhibition-cum-summer academy “Group Affinity” at the Kunstverein München, Slavs and Tatars looked into the notion of the anti-modern from craft traditions to female prayer rituals, including the Slavic harvest festival of dozhinki found across Eastern Europe.

Weeping Window (Chłopaki)

Using the rear window of a Polski Fiat 126, a legendary car manufactured in communist Poland, Weeping Window (chłopaki) features the antimodernist trope – looking backwards at history but moving forwards towards the future – that has become a trademark of sorts of Slavs and Tatars’ practice. From Sartre’s description of Baudelaire as driving forward but with an eye on the rear-view mirror, to Walter Benjamin’s ‘Angel of History’ propelled to the future but facing the rubble of the past, the anti-modern is perhaps best exemplified by Molla Nasreddin, the twelfth-century wise man-cum-fool often depicted riding backward on his donkey. The text – ‘Khajda Khłopaki’ – roughly translates as ‘Let’s go, boys!’ in an archaic Polish, an exhortation to advance forward despite glancing backwards.

A Monobrow Manifesto

Sometimes we must ask stupid questions of otherwise smart subject matter. As a cultural prism or epiphenomenon, the monobrow does just that: the pesky hairs that grow between the eyebrows have a startling way of distinguishing the West from the rest. In Victorian England, the monobrow was associated with delinquent behaviour; in eighteenth- and nineteenth- century French literature, a monosourcil incurred suspicion of being a werewolf; in the US today, it diminishes a child’s social capital in the cruel Darwinism called school. But other skies tell other stories: in Qajar paintings, the monobrow is brandished equally by both sexes. In Iran, it occupies a special place, alongside the eyes and eyelashes, as a trifecta that determines one’s beauty. Across the Middle East and the Caucasus, it is a sign of virility and sophistication. If, in the Global South, the monobrow is hot, in the colder climes of the US and Europe, it’s clearly not.

Reverse Joy (Muharram)

Reverse Joy (Muharram) looks at the perpetual protest movement at the heart of the Shi’a commemoration of Muharram, one of the holiest months of the calendar, for its radical reconsideration of history and justice.

Inserting oneself, flesh and faith, into the events that transpired 13 centuries ago; the collapse of traditional understandings of time; the reversal of roles of men and women; and joy through mourning all demand an equally elastic and muscular understanding of the sacred and the profane that is the down payment towards any meaningful social change.

Reverse Joy

Throughout their oeuvre, Slavs and Tatars often use the term ‘metaphysical splits’ to refer to the combination or collision of two mutually exclusive or antithetical ideologies, registers, concepts within one page or space. No work perhaps better captures this idea of coincidentia oppositorum than Reverse Joy. Through the very simple gesture of a red pigment, the fountain brings together two ends of the spectrum: the innocent with the cynical, the naïve with the violent, through a single color red, for some a festive symbol recalling compote or kool aid, and for others the trace of blood, of martyrdom.

Resist Resisting God

The geometric patterns, upon which the mirror mosaics are based, arrived with the Arab invasions of Persia which introduced Islam in the seventh century. Wood or ceramic was often the Arab medium of choice. The Persians, always keen to distinguish themselves from their Arab neighbours, used mirrors as a bevelled, bling-bling option.

Slavs and Tatars are particularly interested in the revolutionary potential of certain crafts. In the case of Iran, the mirror mosaic best exemplifies the complexity behind the Islamic Republic’s particular brand of anti-imperial imperialism. Much like the Soviets exported agit-prop and socialist realism globally, Iran exports this craft as the aesthetic embodiment of its own ideology to Shi’ite mosques and shrines throughout the region such as the Zeynab Shrine in Damascus.

Hip to be Square

A Polish flag laid over an EP of Huey Lewis’ 1980s hit ‘Hip to Be Square’ and a Kazimir Malevich signature (in decidedly Polish orthography) celebrate the cliché of the plodding Pole by redeeming the methodical, slow-burn nature of the Solidarność strike movement. The seemingly saccharine and innocuous pop song is reinvested with the radicalism of the normal and unsexy, the ‘square’ in English slang, as a successful case study and precedent for other movements of civil disobedience.

In this cycle, the artists look to syncretism – the combination or amalgamation of distinct beliefs, religions, images, languages, or politics – as a third way between the two major geopolitical heavyweights of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: communism and political Islam. Hybrid genealogies are told from the perspective of the region’s fruits: from the persimmon to the mulberry, from the melon to the pomegranate. The history of the region’s flora moves beyond the anthropomorphic focus on historical personages of a region.

Holy Bukhara

A moving example of the syncretism – be it linguistic, religious, or ideological – found in Central Asia, Holy Bukhara is an homage to the Jews of Central Asia, aka Bukharan Jews, whose language, Boxori, provides an unlikely collision of Persian dialect with Hebrew script. Revising the epithet of Central Asia’s holiest city, ‘Bukhara yeh Sharif’ (meaning Holy Bukhara), with one letter, the work celebrates the language as much as the city’s pluralist approach to faith.

Never Give Up The Fruit

Never Give Up The Fruit explores the triangulation of identity against not only the twin ideological poles of communism and political Islam but also the ethnic tensions of Uighurs and Han Chinese. According to legend, the Qianlong Emperor specifically asked that the religious and political leader Afaq Khoja’s granddaughter – known as Xian Fe to the Hans or Iparxan to the Uighurs – be taken alive after Xinjiang was conquered. Her beauty was so renowned that she is said to have been transported back to Beijing in a carriage with felt-lined wheels to ease the long journey. The Uighurs see in Iparxan a symbol of resistance thanks to her alleged refusal to submit to the Emperor’s desires. The Emperor went to great lengths to please her, building a scale replica of Kashgar’s bazaar outside her window to make her feel less homesick, having the famous Hami melons of her homeland delivered, and even allegedly providing her with baths of sheep’s milk. None of this sufficed, nearly driving the Emperor mad and convincing his mother to assassinate his unyielding mistress. Alas, the Han narrative is more mundane, seeing Xian Fe as one of many concubines; in their version of the story, neither her fragrance nor her beauty was enough to save her from the Emperor’s entreaties.

The only part of Central Asia historically under Chinese (as opposed to Russian) rule, the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region is home to the majority of Uighurs and spans 1.6 million square kilometres – roughly equivalent to the surface area of Germany, Spain, and Turkey combined. If, for the West, Islam comes from the East, and the East is often adopted as a shorthand for Islam, the religion of Muhammad comes from the West for the Chinese. Not only does Xinjiang sit just inside Slavs and Tatars’ geographic remit on this side of the Great Wall of China, the province itself is the site of a face-off between the two major geopolitical narratives of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – communism and political Islam, respectively. And crucially, almost without any trace of mediation by the West.

Xinjiang is China’s most resource-rich province, with the world’s largest oil and natural gas reserves; it also has the misfortune of having the lowest population density amongst all Chinese provinces, the result of which has been a large influx of Han Chinese in recent decades, facilitating an Uighur population drop from 75 % in 1953 to 46 % today. The mutual enmity and tension between the Han and the Uighur – from online forums to the very streets of Hotan – is palpable, and conjures up the case of Israel and Palestine, except on steroids. Sandwiched between Russia and China, Xinjiang was a stage during two World Wars, not to mention two communist revolutions thirty years apart. So Uighurs have had their fair share of geopolitical landmines to navigate, with differing degrees of success. In the 1920s, the Soviet Union provided support by establishing unions and workers’ groups, as well as publishing titles catering to the sizeable percentage of Uighurs living in the neighbouring Kazakh and Uzbek Socialist Republics. The early Soviet policy of ascribing a narodnost or ‘ethnicity’ to each and every distinct group of the exceptionally diverse population was one of many attempts to deal with the legacies of Imperial Russia and its transformation into a Soviet society.

There has been no shortage of recriminations and ugly stereotypes on both sides during the many decades of this unhappy marriage: the Han accuse the Uighurs of being lazy, while the Uighurs claim the Han lack proper hygiene. Historic neighbourhoods are razed in their entirety under the pretext of fortifying faulty old constructions, incensing the Uighurs, whom the Han in turn consider ungrateful. Despite being the largest ethnic group by a substantial margin (until recently, that is), the Uighurs are never given top administrative posts or political appointments, instead often holding ceremonial secondary roles.

Dunjas, Donyas, Dinias

Long-standing Serbo-Turkic enmities make peace in Dunjas, Donyas, and Dinias. The word for the fruit “quince” in Serbian – dunja – is a common name given to women as a symbol of beauty, and happens to be the homonym of the word “world” in Arabic and Turkic: donya.

Fragrant Concubine

Hanging Low

Via the puckered lips of someone who smiles backwards, Hanging Low pays homage to the conflicted relationship to memory, to pluralism, and to joy through mourning. Józef Wittlin’s Mój Lwów (My Lvov) laments the loss of the plural identities, languages, and affinities in a city that was once Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, and German, and warns of memory’s selective, if unstated, agenda. He speaks of the strange mix of the sublime and the street urchin, of wisdom and cretinism, of poetry and the mundane – as a special indefinable taste: bittersweet.

How-less

“You Know of the How / I Know of the How-less” is attributed to Rabia al-Adawwiya, a Muslim saint and Sufi mystic. Considered to be one of the first female Sufis, she is credited with pioneering the notion of Divine Love central to the veneration of God in Sufism.

Long Live The Syncretics

Modeled after the branch of a mulberry tree whose fruits are white or black, Long Live the Syncretics delicately dangles ribbons as a nod to the progressive, syncretic approach to Islam in Central Asia, where Buddhist, Hindu, and pantheist rituals are incorporated into the belief system.

The Dear for the Dear

Before the Before, After the After

A fruit of caricature, of the Other, the watermelon often serves as a racist shorthand for African-Americans in the US; while in Russia it recalls the contested Caucasus and in Europe the countries of origin of the migrant populations, be it Turkey, North Africa or elsewhere. Placed in the two Robert Oerley pots at the entrance to the Vienna's Secession, the watermelons encourage visitors to experience the “Not Moscow Not Mecca” exhibition not just cerebrally, but also sensorially and affectively.

Triangulations

Stalinist policy towards Central Asia – ‘To Moscow Not Mecca’ – aimed at replacing Islam with communism as the chief belief system of the local Muslim population of the Soviet Union. Not Moscow Not Mecca chooses not to choose between the two major narratives of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, that is, revolutionary communism or political Islam. Instead, each of the Triangulation road markers brings together a resolutely secular city with one known for its sacred importance.

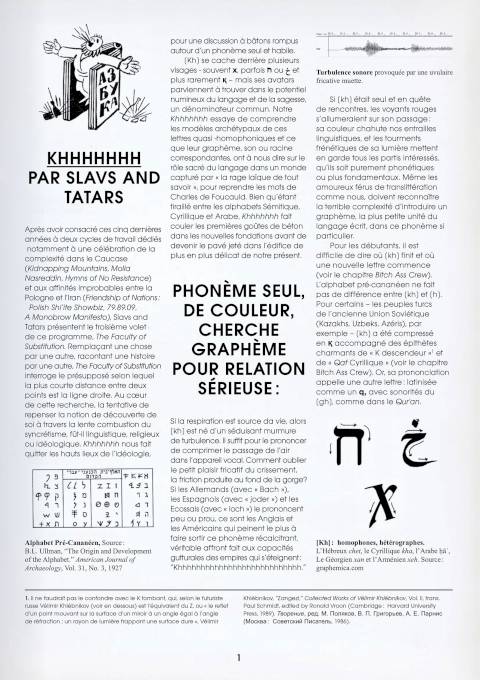

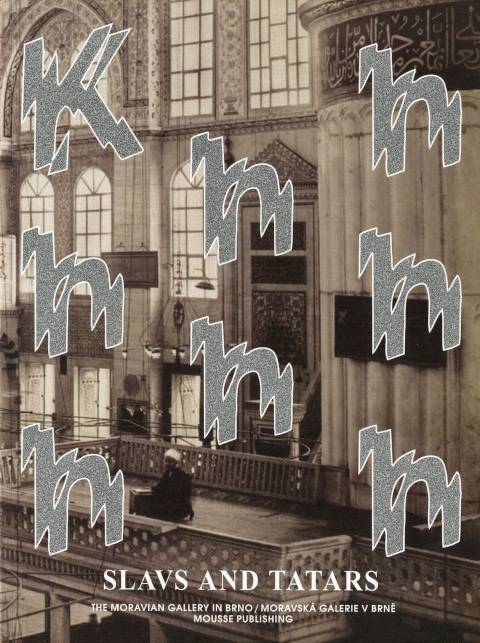

The march of alphabets has often accompanied the ascension and fall of empires and religions. In Language Arts, the collective unteases the politics of alphabets: the many fraught, often forgotten yet palpable attempts by nations, cultures and ideologies to ascribe a specific letter to a sound. The book Khhhhhhh (Moravian Gallery, Mousse / 2012) examines, literally, the throat as a space of phonetic and sacred agency via the Hebrew, Russian and Arabic letters for the fricative [kh] while Naughty Nasals looks to the nose, as a ‘site of resistance in the Slavic and Turkic languages’.

False Friends

False Friends

Księgożerstwo (Bibliophagy)

Sculpture by Olga Micińska. Part of the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw’s Primary Forms educational program, Księgożerstwo is a stamp and ex-libris challenging adolescents to consider which texts they consider canonical and why.

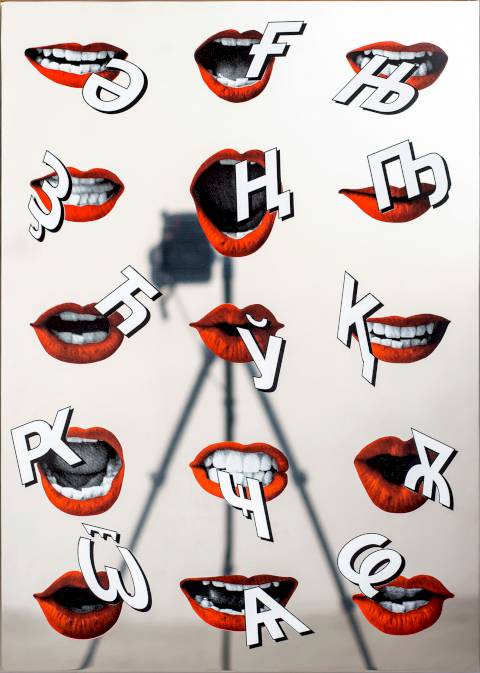

Qatalogue

A mouth emits Cyrillic letters which failed to take hold in various languages, approximations of sounds which did not exist previously in Russian or other slavic languages.

Cyril

Ҹ

Deepthroat Dipthongs have nothing

on you, Jamal, or as our Albanian Apollinarians

say, Xhemal. The Americans called you

the jump /dz/ for one

OlaҸuWon

Hakeem the Dream

No oldies but goodies Kareem

Abdul Ҹabbar who ҹuggled to the rear

empires under Ҹahangir

Қ

The Qit Qat Qlub

headlines the Ka

with a descender

The Qabaret

of your thighs,

The Qutb

of your beloved shuns the Qatalogue

of your lies

Њ

Rudaki wrote about the wine

Hafez and Saadi the divine

but only your seedless

Grapes the gift of caprice

the whine of so

many yes-ño

да нет

jeins

shouldering the

velars of volcanic tides

Ҩ

We are born oui

people and non! people

Ҩui the people fear not

Amiran nor his

Lean and mean

Promethean phonemes

So many echoes in

Noses half Abkhaz

Half aquiline

Jęzzers Język

Jęzzers język celebrates the nasal phonemes specific to the Polish language through a retro exclamation: Yowzers! Unlike most other Slavic languages, the Polish language has prominent nasal phonemes – ‘ą’ and ‘ę’. These letters have provided an unlikely source of self-determination and resistance in the face of pan-Slavism, Russian imperialism, amid a panoply of perceived or real threats.

OdByt

When broken down into its two component syllabes, odbyt (lit. ‘rectum’ in Polish) means ‘from being’. While Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde clearly indicates which orifice the French artist considered a myth of origins, Odbyt argues for the a**hole as the origin of humanity. Meaning ‘from’ in several Slavic languages, the preposition ‘ot’ used to exist in old Church Slavonic as a Cyrillic letter unto itself: ‘Ѿ’.

Larry Nixed, Trachea Trixed

Larry Nixed, Trachea Trixed looks at various attempts to Cyrillicize sounds or phonemes that did not previously exist in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet, one of many attempts to extend or embed Soviet influence, with a decidedly more sensuous, if not sexualized, approach to the traditionally cold, clinical approach of linguistics.

Ezan Çılgıŋŋŋŋŋları

Enforced from 1932 to 1950, the Turkish translation of the traditionally Arabic call to prayer, or ezan, was perhaps the most controversial piece in an elaborate constellation of language reforms in the Republic of Turkey. To begin with, translating Allah to Tanrı problematizes the very central tenet of the faith – the unicity of God (tawhid) – through the use of a pre-Islamic, shamanist term dating to the era of the Mongols and Genghis Khan, meaning ‘the great sky’. Ezan Çılgınları – literally, the ‘call-to-prayer crazies’ – was the term used for those who defied the authorities’ enforcement of the Turkish ezan by climbing minarets and performing the call to prayer in the original Arabic. Despite a rocky ride, the language reforms known as dil devrimi advanced relentlessly...until 1950, when the call to prayer was changed back to Arabic. To this day, many Kemalists see in this reversal the first of many concessions leading to the increased public face of Islam in Turkish society and politics of the past decades.

For the eighth Berlin Biennale, Slavs and Tatars revisited this particular episode through an unwieldy restaging of the ezan. In collaboration with musician Jace Clayton (DJ /rupture), Turkish call to prayer was recorded with Vocaloid™ for an entirely computer-generated, a cappella summons or chant. If once Young Turks, Gökalpists, and other reformists considered the Turkish replacement a way of anchoring the young republic to the West, five decades later it seems to have had the exact opposite effect: reactivating a thoroughly different understanding of Turkey’s linguistic and cultural genealogy. If the Ottoman Empire pushed southwards and westwards, then Ezan Çılgıŋŋŋŋŋları pushes east towards Central Asia – not just the Balkans or the Middle East – extending across the steppe, nearer to China than Europe.

The distinct Turkish (as opposed to Arabic) phonetics of the call to prayer sheltered it from potential Islamophobic attacks or protests from residents surrounding its outdoor installation at the Haus am Waldsee. Set on the bucolic slope of grass outside the exhibition space, the lake acts as nature’s own loudspeaker, pushing the call to prayer further outwards. Due to the peculiar tonalities of the language, the Turkish ezan is far more consonant-heavy, especially compared to the more open-vowelled Arabic adhan. While the recognizability of Allāhu akbar makes it a vocal lightning rod, the same could not be said of Taŋrı uludur.

Listen to audio file here

The Naughty Nasals

The Naughty Nasals identify the nose as an unlikely site of sonorous resistance to the instrumentalization of scripts, or alphabets. The ‘Ѫѫ’ (wielki jus) and ‘Ѧѧ’ (mały jus) invoke nasal sounds that have disappeared from most Slavic languages but remain as ‘ą’ and ‘ę’ in contemporary Polish. As mobile confessionals, they are a testament to one of the lesser known, aborted attempts to Cyrillicize the Polish language in the nineteenth century. Despite the often very clinical approach of linguistics, the various organs of language represent a distinct erogenous: be it the teeth, lips, mouth, tongue, neck, ears or nose. The sequel to the artists' publication Khhhhhhh, the similarly title book The Naughty Nasals (Galeria Arsenal, 2014) explores the nose as a rupture from the norm of language poltiics across the Polish and Turkic languages.

Swinging Septum

Long eclipsed by the mouth as a source of libidinal linguistics, Swinging Septum restores the nose as an equally discursive and desirous organ of language. A flat silhouette nose sways from left to right, evocative of the facial acrobatics the septum must perform to reach the sonorous heights of /ɛ̃/ or /ŋ/ to name but a few.

Nose Twister

Turkey today has only one measly alphabet. The Turkish language put the thorny issue of alphabet politics to rest in little over eight decades: the massive alphabet reform launched in 1928 by the Türk Dil Kurumu (Turkish Language Institute) stands uncontested to this day. Even a reactionary Salafist in Turkey might think twice about bringing back the Arabic script: the Romanization project in Turkey was, as Geoffrey Lewis put it best, ‘a catastrophic success’.

Among the letters that didn’t quite make it from the sinking ship of Ottoman Turkish to the newly Romanized shores was the 28th letter of the alphabet, a little twitch at the back of the nose, the ڭ or Kêf-î Nûni. Until 1928, the Turks had two different <n> sounds: the conventional ن (n), the one you’d be happy to introduce to the parents, as in نهایت, ‘never’, or ‘nomenklatura’; then there’s the ڭ, a more peculiar, eccentric type of n, pronounced in the depths of the nose, as the <ng> in ‘sing’. The very pronunciation of <ng> has all the first-degree Oriental trappings of a snake-charmer, or more aptly, a gong. For good reason: <ng> figures among the most common Chinese surnames, with an extensive Wikipedia entry dedicated to ‘Notable people with the surname Ng’ to boot. In Turkey, words that used to have the <ng> have progressively whitewashed it out of existence, like blacklisted party members from an official photo – an unwanted reminder of phonetic, linguistic, if not national disruption. Dengiz became deniz (sea), tangri became tanri (all-encompassing sky).

Reverse Joy (Kha)

Throughout their oeuvre, Slavs and Tatars often use the term ‘metaphysical splits’ to refer to the combination or collision of two mutually exclusive or antithetical ideologies, registers, concepts within one page or space. No work perhaps better captures this idea of coincidentia oppositorum than Reverse Joy. Through the very simple gesture of a red pigment, the fountain brings together two ends of the spectrum: the innocent with the cynical, the naïve with the violent, through a single color red, for some a festive symbol recalling compote or kool aid, and for others the trace of blood, of martyrdom. Here, three iterations – in Hebrew, Cyrillic and Arabic alphabets – of the phoneme [kh] dance ceremoniously around the red fountain.

Rahlé for Richard

Rahlé for Richard uses the form of the stand for holy books (or rahlé), a leitmotif in Slavs and Tatars’ work, given the importance of books and language in their practice. Here, the tongue sticks out, a gesture equally of interjection and emphasis, as in a shout or cry. Rahle for Richard suggests the transition from oral to print cultures: whether it’s the relatively late arrival of Islam to print, despite having access for several centuries, or the hesitation of the Orthodox faith to adopt print. The homage to Richard Artschwager is manifold: Artschwager’s consistent use of surface as something with depth, beguiling, uncannily thick. His veneers belie something else, be they pianos or other. In S&T, the artists turn to humor, pop, witticisms, and rumours with a similar understanding of surface, of the very thick first degree, both revealing and obscuring subsequent layers of meaning.

Love Letters

Ten tufted carpets, each equal in dimension, investigate language as a source of political, metaphysical, even sexual emancipation. By revising original drawings by Vladimir Mayakovsky, Love Letters address the very charged if slippery issue of language through one of its best-known, if conflicted, champions. The tongue’s yin and yang, its bipolar disorder – as a source of man’s greatest achievements and yet a cause of his tragic failures – finds its appropriate poster-boy in the figure of Mayakovsky, whose Futurist experiments with language and embrace of the nascent Bolshevik regime resulted in some of the most important works of avant-garde art and literature. Yet his own instrumentalization of language for the purposes of the revolution eventually led to his own disillusionment and suicide, a watershed moment widely believed to mark the beginning of Stalin’s terror.

Through caricature, the carpets depict the wrenching experience of having a foreign alphabet imposed on one’s native tongue and the linguistic acrobatics required to negotiate such change. In particular, the carpets tell two parallel stories: that of the Bolsheviks’ forced Latinization and later Cyrillicization of the largely Turkic peoples of the Russian Empire, and the 1928 language revolution of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – Turkey’s first president – in which the Turkish language was converted from Arabic to Latin script. The casualties of these linguistic takeovers – lost letters and mistranslations – are given center stage here as a testament to the trauma of modernization.

Qit Qat Qa

The phoneme [gh], corresponding to the Arabic letter ‘qaf’, is pronounced even further back in the throat than [kh], the subject of Slavs and Tatars’ publication Khhhhhhh. Often transliterated in the Latin alphabet as ‘q’ or ‘k’ (in Qur’an or Koran, for example), the Soviet attempt to Cyrillicize ‘qaf’ led to drafting a wholly new grapheme, a ‘ka’ with a descender, which is still in use in Tajikistan but abandoned in other Central Asian countries. Beyond a mere letter, qaf is the Sufi name of a cosmic mountain, home to the mythical bird the simorgh – a precursor to the жар-птица (zhar ptitsa, meaning firebird) found in Slavic fairy tales, the phoenix, or, more recently, Banshee from the motion picture Avatar (2009).

Madame MMMorphologie

Madame MMMorphologie continues Slavs and Tatars’ interest in language as a form of affective if not affectionate emancipation. Winking at passersby, the tome also speaks to the collective’s bibliophilia: an anthropomorphic edition of Molla Nasreddin, the legendary 20th century Azerbaijani satire the artists translated, bears witness to the alphabet politics of the Turkic languages under Soviet rule.

Other People’s Prepositions

A preposition is a word explaining a relation to another word. And perhaps no preposition is as central to Slavs and Tatars’ specific cosmology as the word ‘from,’ given the artists' interest in historiography, research, and genealogy. The preposition ‘from’ also indulges an anti-modernist perspective – facing the past but moving forward towards the present, like Molla Nasreddin, the 13th century Sufi wise-man-cum-fool, often depicted riding backwards on his donkey.

Literally ‘from’ in several Slavic languages, the preposition Ѿ or ot used to exist in old Church Slavonic as a Cyrillic letter unto itself. OPP tries to restore this ligaturial luxury – a combination of the Greek Omega and Theta – through a meditation on the preposition’s more carnivalesque tenor.

Tongue Twist Her

A pole often found in nightclubs or sex bars has traded in the topless dancer for something no less racy: a giant, fleshy tongue. The alphabet changes in many parts of the former-Soviet, largely Turkic speaking world from Arabic script to Latin to Cyrillic back to Latin in 60-odd years has made whole populations immigrants within their own language. Tongue Twist Her shows not peoples or nations that are liberated, but the dizzying and devastating swings – in this case lingual – of phonemes, graphemes, and organs.

ωXXX

Meaning ‘oops’ in Greek, ωXXX (okh) is an example of linguistic and cultural transmission, with the great omega’s sassy side highlighted by the proximity of a gang of x’s for a particularly attractive alliterative stuttering. Not by coincidence, the ‘x’ is a Cyrillic and Greek letter for Slavs and Tatars’ signature guttural phoneme, [kh], and subject of their publication Khhhhhhh.

Öööps

One of the principal arguments for changing the Turkish script from Arabic to Latin – the inability of the Arabic alphabet to accommodate the full range of vowels in Turkish, namely the ‘ü’ and ‘ö’ – here serves as both sophisticated as well as lowbrow, slapstick humour. This lengthened version of the word ‘kiss’ in Turkish presents the vowel change as equal parts typo/ editing error and modernist mini-miracle – if not metaphysical mishap.

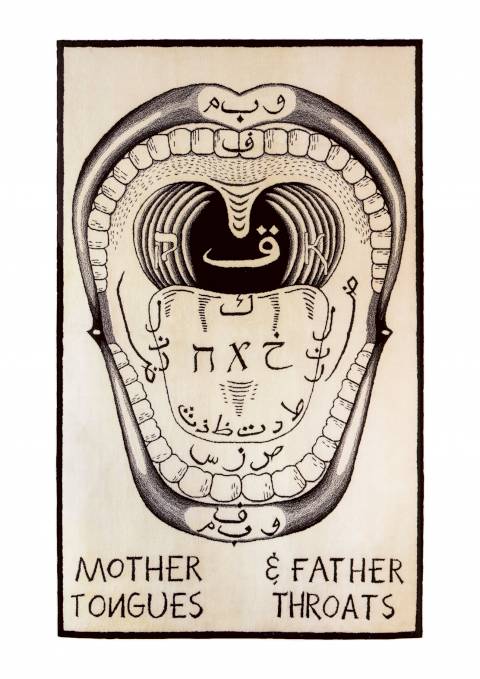

Mother Tongues and Father Throats

A diagram showing letters of the Arabic alphabet and the corresponding part of the mouth used to pronounce these letters, Mother Tongues and Father Throats turns to the throat as a source of mystical language – as opposed to the the tongue's more profane, transactional role. Here, the artists have added the letters for guttural phonemes [gh] and [kh] in Cyrillic and Hebrew as a nod to these letters' importance across disparate fields such as Russian futurism, Kabbalist gematria, and Sufi exegesis.

Kh Giveth and Kh Taketh Away

Kh Giveth and Kh Taketh Away further mine the phoneme [kh] as a source of mystical if not fricative potential. The mirrors champion the throat and its ability to constrict as opposed to facilitate the passage of air in this decidedly anti-imperialist phoneme.

Mirrors for Princes refers to a medieval and renaissance genre of advice literature in both Islamic and Christian cultures that counselled rulers on matters of statecraft, the body politic, and good governance. Mirrors for princes (specula principum or Fürstenspiegel) represented an early form of secular scholarship that raised the level of statecraft to that of religious jurisprudence or theology. For the artists, aside from producing and foreshadowing a ‘care of the self’ that was instrumental in western modernity, mirrors for princes is a form in which critique is presented as a form of gift-giving or hospitality.

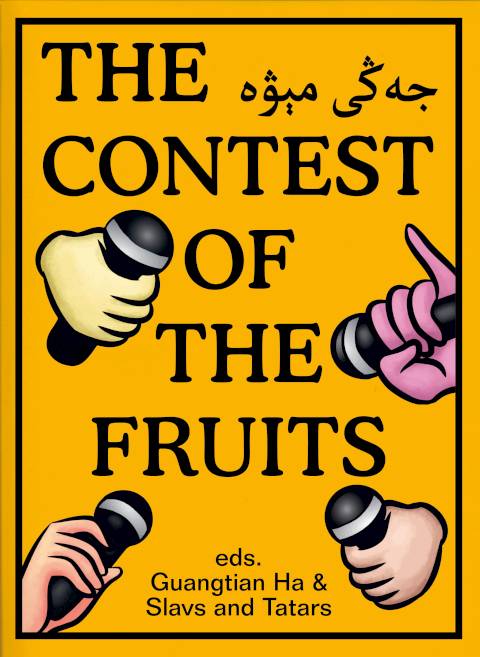

The Contest of the Fruits

A 19th century Uyghur poem is staged as a proto-Turkic rap battle between 13 fruits in this seven minute animation.

Aşbildung

Linking spiritual and intellectual nourishment, Slavs and Tatars ask us to consider mind and stomach as one entity, a literary, imaginative space added to a no less discursive if more commercial operation. For the 2021 Public Commission of Osnabrück, the artists collaborated with a local döner kebab shop, adding a literary element to the usual transactional one of fast food. Placemats featuring excerpts from Kutadgu Bilig, the 11th century epic Turkic poem, dürüm wrappers with the artists Kitab Kebab and a public performance program are among the artist interventions within the venue.

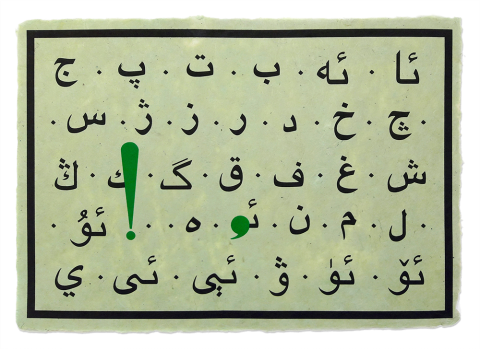

The Alphabet (Uyghur kril yéziqi)

The Alphabet revisits Marcel Broodthaers’ Poèmes industriels, replacing the Latin alphabet with an Cyrilized Uyghur one. The original exclamation of ‘OK!’ survives unscathed, despite the transmogrification from the secularized world of Latin.

Who are you?

The Arabic word هو (pronounced ‘who’) is often used by mystics in Islam to evoke the Divine. In particular it is chanted by Sufis rituals incarnations (zikr) like a mantra. However, the word هو also literally means ‘he’, using a gendered masculine form to express God. Who are you? poses the existential question as one not only between secular and holy but also between the various normative gender variations of the former and latter.

Saturday

An act or document freeing a slave, several manumissio (written on left and right sides of the work, in Hebrew and Greek) have been found in Crimea. According to the Hebrew bible, slaves were to be freed in the seventh year, known as the Saturday or Shabbat year, after six years of labour, regardless of their origin, performance, or profile. Given the struggle of Jews throughout history, from the Exodus to pogroms to diaspora, this was a rather progressive if not generous approach to a contentious issue, especially when compared with that of their Christian and Muslim contemporaries.

Alphabet Abdal

Though considered to be the sacred language of Islam, the Arabic language and alphabet is equally the language of Middle Eastern Christians. Featuring an exodus, Alphabet Abdal commemorates the endangered Levantine, Hijazi origins of Christianity, and, with it, the heritage and language that expresses these traditions. The text reads: ‘Jesus, son of Mary, He is Love’.

Stongue

Elongated and straightened, a heart morphing into a tongue attempts to speak but shows sincerity to be a constraint as much as an opportunity.

AÂ AÂ AÂ UR

An oversized set of prayer beads, sprouting from the ground, AÂ AÂ AÂ UR addresses the balance between seclusion and society, spirit and state, echoes of which we continue to find in the US, Europe and the Middle East today. The beads’ scale and momentum, launched from below the surface, invite a quiet playfulness, in particular with regards to a subject matter often brushed under the proverbial rug: the potential for a progressive agency in faith.

Bazm u Razm

The glass combs of Bazm u Razm swing between the afro-combs of hip hop culture and talismanic forms found around Uighur tombs in Xinjiang, western China, where they are used as family designations or seals. The grooming or taming of hair has been tied to that of civilization and order for some time, with the curly, frizzy, unruly often construed as a social, sexual, or psychological menace. In Bazm u Razm, literally ‘banquet or battle’, the combs are portrayed as markers of order and violence: the Turkic peoples extending from Mongolia all the way to the Balkans were renowned for their skills as warriors as well as hosts.

Lektor

The multichannel audio work Lektor (speculum linguarum) from 2014 contains text drawn from the eleventh-century Turkic mirrors for princes Kutadgu Bilig (Wisdom of Royal Glory), read in its original Uighur with several voice-overs. The selection of translations (German, Turkish, Polish, Arabic, Scots Gaelic, Aboriginal Jagera, Flemish, Danish, Spanish, and Persian) for the voiceover or ‘dub’ traces the exhibition history of the piece through the languages of venues. Used for films in Poland and Russia, and elsewhere only for news segments, the simultaneous playback of a voice-over translation, a technique known also as Gavrilov translation, makes for a disruptive experience, touching on issues of legibility, authenticity, and language as a form of hospitality.

Written in the eleventh century in Kashgar, in what is known today as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in western China, Kutadgu Bilig is a cornerstone of Turkic literature. The importance of the work is difficult to overstate: it is to Turkic languages what Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh is to Persian, Beowulf to English, or Nibelungen to German. In rhymed couplets (masnavi), four main characters personify four abstract principles: Justice, Fortune, Intellect, and Contentment. Their debates serve as a rare example of Socratic dialogue in a Muslim tradition known for its theological emphasis on the One. A central discussion takes place between a Sufi dervish and a vizier to the king, whose names are, respectively, Wide Awake and Highly Praised – addressing the balance between seclusion and society, spirit and state, whose contours resonate today as much as a millenium ago.

The Squares and Circurls of Justice

Turbans, some designating students, others elders, greet visitors upon entry. The act of removing headwear or disrobing, like that of coats or outerwear, implies entry to an intimate if not sacred space, as opposed to the more secular public space of a cultural institution.

Hirsute Happily with Hairless

Zulf

A brunette and blond rahlé (or book-stand used for holy books) offers another take on the seduction of texts and exegesis.

Irokez

The grooming or taming of hair has been tied to that of civilization and order for some time, with the curly, frizzy, unruly often construed as a social, sexual or psychological menace. In our Mirrors for Princes book, Lloyd Ridgeon’s essay “Shaggy or Shaved” expands upon the rituals of grooming in Islam, particularly in various Sufi sects.

Bandari String Fingerling

The daily taming of hair is an act of civilization, battling the unruliness of the body. In this sense the rituals of daily existence, such as combing one’s hair, echo as objects the counsel of the Mirrors for Princes genre. Like the genre of medieval advice literature, grooming has also undergone an increased profanization in recent centuries. Once a sacred, ritual practice, today it is often a mere cosmetic transaction or at best a tribal, gendered belonging.

Bandari String Fingerling portrays the plucking of facial hair – which follows strictly gendered lines, acceptable for men, unacceptable for women – as a precious act of penitence.

5 O’Clock Shadow

The grooming or taming of hair has been tied to that of civilization and order for some time, with the curly, frizzy, unruly often construed as a social, sexual or psychological menace. In Slavs and Tatars' Mirrors for Princes, Lloyd Ridgeon's essay “Shaggy or Shaved” looks at the rituals of grooming.

Dil be Del

The phrase “speaking from the heart” is taken quite literally in this work as the tongue – the organ of speech – is grafted directly onto the heart. The title, Dil be Del, further emphasizes this jumble of body parts through a composite of the words for “tongue” and “heart” in Turkish and Persian respectively.

To Beer Or Not To Beer

Those familiar with the dregs of college – also referred to as ‘frat-boy’ – humour indigenous to Anglophone countries, not to mention those holiday destinations frequented by the aforementioned (Cancun, Amsterdam, etc.), might have encountered a short-sleeved garment of clothing emblazoned with an illustration of a beer and the question: ‘To beer or not to beer?’ Another specimen commonly found features two depictions of a brewed beverage with the question in another, slightly altered iteration: ‘Two beers or not two beers?’

By rewriting the well-known passage from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet – ‘To be or not to be’ – these modified invocations to imbibe alcohol have squandered the existential gravitas of the original, despite centuries of clichéd usage. To drink a beer or not to drink a beer (nay, two beers!) remains primarily a question of consumption. For To Beer or Not To Beer (2014), we looked to transliteration in an effort to elevate the popular back to the sublime. Normally transactional, transliteration here inches closer to the transcendent: transcribing ‘To beer or not to beer’ in the Arabic script, the sacred script of Islam, redeems the existential query of the original. To imbibe alcohol – for a Muslim, at least – entails a complex web of religious, cultural, even phenomenological questions around identity.

Hung and Tart

Hung and Tart features a heart that becomes a tongue, enacting a synapsis, or short cut between the conception of speech, symbolic and sincere, and its delivery. The wordplay of the title also alludes to the affinitiy between the organs of speech and those of sex.

Coinciding with the World War I centenary, and made in the wake of the European migrant crisis of 2015, Made in Germany sheds light on Germany’s little-known historical relationship with Islam and ‘the East’.

MERCZbau

MERCZbau revisits the intertwined histories of the Ukrainian city of Lviv and the Polish city of Wroclaw as seen through the prism of a particularly eastern Orientalism. The Berlin-based artist collective Slavs and Tatars have created a speculative range of merchandising dedicated to the defunct Department of Oriental Studies of what was once known as the Jan Kazimierz University of Lwow, acting as if age-old traditions of scholarship and inquiry about “the East” had survived the Polish population’s forcible westward journey after World War II. The exhibition’s title alludes to German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters’ landmark sculpture Merzbau, a room-sized installation that was destroyed in World War II. MERCZbau thus offers a reflection on the human drama of migration as well as the shifting meanings of our enduring East/West divides, made so much more poignant by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Long Lvive Lviv

Long Lvive Lviv. Слава за Бреслава revisits the intertwined histories of Lviv and Wroclaw, from the particular perspective of orientalism. Following World War II, as Lviv was incorporated into the Ukrainian Republic of the Soviet Union, the Polish population of the city was forced to relocate to Wroclaw, a German city given to Poland at the Potsdam Conference in exchange for the loss of its Eastern territories. Alongside the massive population transfers, scholars at the renowned Jan Kazimierz University in Lviv (today the Ivan Franko National University) were forced to flee and a majority took up posts at Wroclaw University. One key department, however, did not survive this deportation.

Botschaft eines Liebhabers

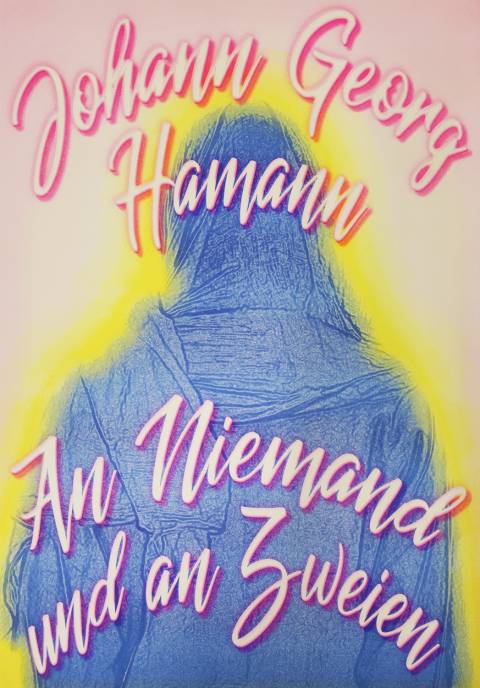

“For the boredom of the audience, from a lover of boredom.” Johann Georg Hamann (1730–1788) was a radical Enlightenment thinker and philologist who argued against the excessive reliance on the rational. His cryptic, playful writings are an urgent reminder of the compatibility of reason and faith, the mystical and scientific. Curated by Ruth Ur and commissioned by Deutsche Bahn for the S-Bahnhof Friedrichstrasse station.

Honey Dew

Honey Dew introduces two quintessentially exterior vernaculars—that of a melon market and a riverbed—found across Central Asia to an interior one, via a canvas wallpaper. The original photo is taken from a publication by Aleksander Rodchenko on the occasion of 10th anniversary of communism in Uzbekistan.

Soft Power

Soft Power revisits the strict threshold which a door traditionally represents–especially in the Middle East where distinct knocks are provided to differentiate between genders–via a carpet, a material often found on floors.

Ha’mann in the hood

Half-sculptural intervention and half-scenography, the carpet is dedicated to Johann Georg Hamann, the enfant terrible of the anti-Enlightenment or, in his own words, ‘to Nobody and to Two’.

Gut of Gab

Disembodied lips allow speech from elsewhere, from other organs, be it the stomach (ventriloquism) or the genitals. Gut of Gab is an homage to Johann Georg Hamann, whom Kierkegaard called “the greatest humorist in history.”

Stilbruch

A leitmotif in S&T’s practice, a rahlé or stand for holy texts is mirrored ad infinitum, a further elaboration on the act of reading as a liturgical gesture.

Bicephalic

“The history of Russia is the history of a country which colonizes itself”

- Klyuchevsky

Unlike the more heteronormative eagles on the Polish or German flags, the eagle on Russia’s coat of arms swings both ways, facing both East and West. Taking its cues from Byzantine heraldry where emperors were also Christ’s representatives on earth, Bicephalic layers Russia’s particular position as Europe and Asia, self and other onto the bi-sexual flag, arguing for a geopolitical identity through non binary sexuality.

Weeping Window (Morgenländer)

In exile and deposed from power, Kaiser Wilhelm once confided to Oswald Spengler, author of the 1918 book Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the Western Order): “we are orientals (Morgenländer), and not westerners (Abendländer).”

The The Servant Servant of of the the All-Forgiving All-Forgiving

The renowned Dutch Orientalist Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje converted to Islam in late 1884, and took the name ‘Abd al-Ghaffar’, which translates roughly as ‘the servant of the all-forgiving’. Eager to access Mecca and witness the pilgrimage rites about which he had written his doctoral dissertation, ‘The Festivities of Mecca’, Snouck Hurgronje went so far as to circumcise himself, and purchase and marry a slave in order to better fit into Meccan society. His photographs of Mecca and the Ka'aba, published in Bilder-Atlas zu Mekka (1888) and Bilder aus Mekka (1889), are amongst the first of the Holy City and became key references in the field. Except for one small detail: most of the photographs were not taken by him.

Rather, they were the works of a local Meccan photographer and doctor, with whom Snouck Hurgronje collaborated while in Mecca and whom he would later instruct or art-direct from a distance, when back in the Netherlands. If any further proof were needed that authorship is often a spiked drink, this doctor’s name was also ‘Abd al-Ghaffar.’

Snouck Hurgronje kept his conversion a secret, for fear of the impact it might have on his scholarly and societal reputation. Nonetheless, more than a century later, his conversion continues to be debated: was it an authentic expression of faith or simply a ruse, a means to an end?

Sarazenen

The emphatic, Arabic versions of the latin letters S/Z, ظ/ ض grace the cover of Süddeutsche Zeitung further highlighting Slavs and Tatars' investigation of language as a nexus of sensualized politics. These letters are considered highly specific to the Arabic language with one epithet for Arabic being “the language of the dhad” in reference to the letter ظ).

Reverse Dschihad

On November 8, 1898, Kaiser Wilhelm II raised a toast to the Ottoman Sultan during a visit to Damascus and pledged his friendship and the friendship of Germany to 300 million Muslims. To be fair to Wilhelm, it was his first trip to the Holy Land and all that very heavy history can make you light-headed, but your chances of success drop significantly if you think a toast is woke with Islam. Part of a concerted strategy to “set the East aflame,” Max von Oppenheim, founder and first director of the Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient (Intelligence Bureau for the East), conceived a plan with Enver Pasha, the Ottoman War Minister, for Sultan Mehmed Reshad V to declare jihad on November 11, 1914. Though global, this jihad was entirely partial: against some infidels (France, England and Russia) but with other infidels (Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire).

The publication by the NfO in 1915 of a propaganda paper called El-Dschihad is perhaps the most curious piece of this pie. Distributed to Muslim POWs held at a camp called Halbmondlager (Half-Crescent Camp) in Wünsdorf, just outside Berlin, and published in Russian, Arabic and Turko-Tatarisch – the languages of the Muslims targeted, living under Russian, French or English rule – El-Dschihad intended to stoke anti-imperial sentiment in territories belonging to the Entente Powers, in an effort to win these Muslims over to the side of the Central Powers. The hope was that they could eventually be persuaded to return to the front on the side of certain infidels, against other infidels; or alternatively, to their respective homelands to fight against their colonial rulers. At Halbmondlager, prisoners were treated to particular luxuries, including recreational games, halal meat and a custom-built mosque, the first of its kind on German soil. If the book cataloguing the West’s instrumentalisation of political Islam is a door-stopper, Dscherman Dschihad would be one of its more entertaining chapters.

Made In Germany

The renowned mark of quality was used to mock Germany’s behind-the-scenes role in the declaration of jihad, or holy war, by the Ottoman Sultan against the Entente Powers (France, England, and Russia) during the First World War. Arabic letters phonetically spell out ‘Made in Germany’ using a military alphabet devised by the Ottoman Minister of War, Enver Pasha (1881–1922) in 1913 for use in wartime correspondence. An early precursor to script reforms, its separation of the Arabic letters into distinct graphemes was thought to facilitate the reading and writing of Ottoman Turkish.

Both Sides of the Tongue

In one of his seminal essays, Roland Barthes deconstructs Honoré de Balzac’s novella, S/Z, about a French aristocrat who falls in love with a star of the Italian opera only to find out she is a he, that the singer is in fact a castrato. To Barthes’ binaries of he/she, revealed/concealed, homosexual/heterosexual, Slavs and Tatars add an extra one: the Arabic letters of ‘ﻆ‘ / ’ﺽ’, the emphatic versions of the original S/Z. Both Sides of the Tongue further highlights the artists’ investigation of language as a nexus of sensualized politics, via two letters considered highly specific to the Arabic language.

Dschihad

A slippage of scripts suggests a verb, an action, and yet another meaning to the already-loaded terms of jihad and Warsaw. The past participle ‘had’ and ‘saw’ disarticulate the traditional signage associated, respectively, with a mediatized term such as jihad and a city devastated by war. The awkwardness of four consecutive consonants – to approximate the [d͡z] phoneme in German – highlights the term Dschihad as irrevocably foreign or Other.

The Alphabet

The Alphabet revisits Marcel Broodthaers’ Poèmes industriels, replacing the Latin alphabet with an Arabic one. The original exclamation of ‘OK!’ survives unscathed, despite the transmogrification from the secularized world of Latin to the sacred script of Arabic.

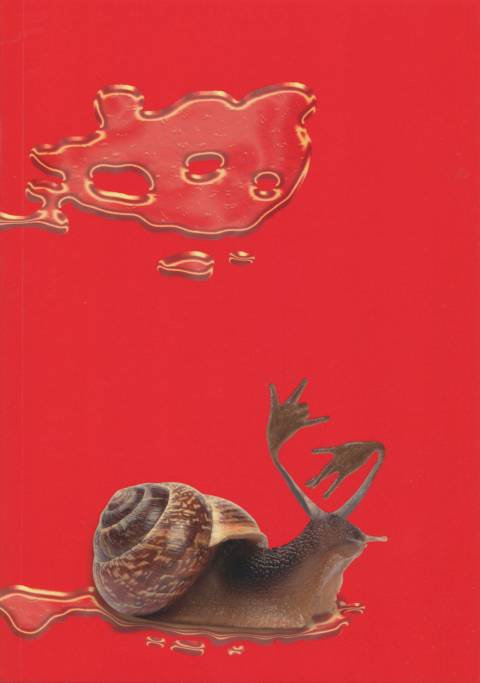

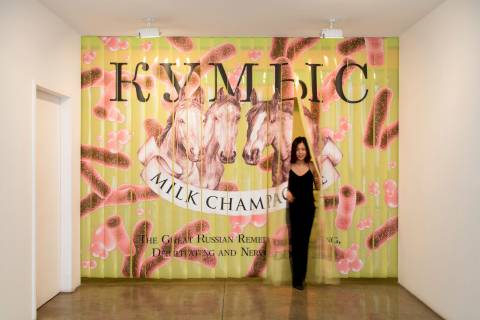

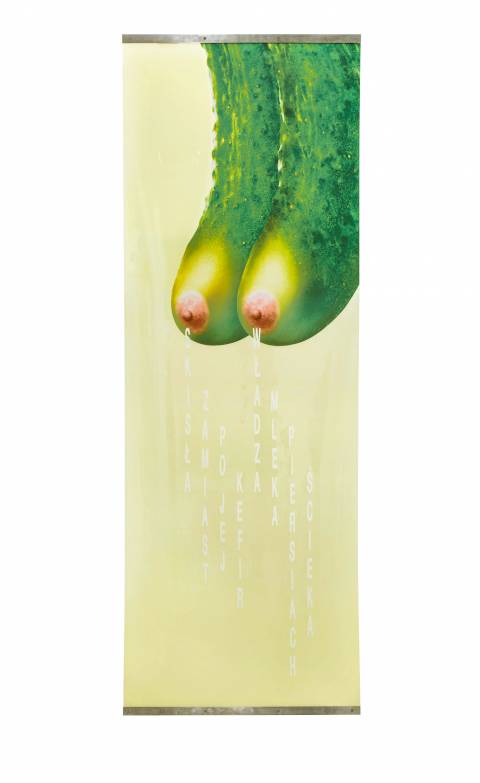

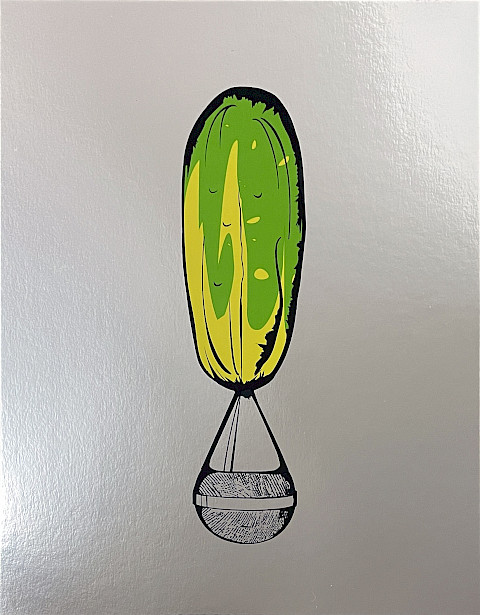

Whether microbes or mitochondria dwelling furtively on the skin or non-native agents living within us: bacteria comprise one kilogram of the average human body. Pickle Politics looks to the practices and symbolism of fermentation, constructing a political argument using notions of the rotten, the spoiled, and the soured.

Lytes