The cycle Régions d’être spans the unwieldy geographical remit of Slavs and Tatars – between the former Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China – while also serving as a prequel to the collective’s practice. Régions d’être is the collective’s term for an area that falls between the cracks of history and general knowledge: largely Muslim but not the Middle East, largely Russian speaking but not Russia, and having a complex relationship with the nation. Yet rather than representing a specific value, history or culture, this ‘region of being’ is as much an imagined, poetic geography as it is a real, political and historical geopolitics.

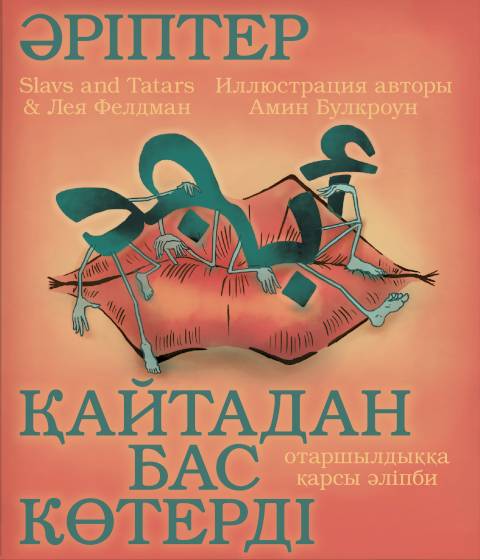

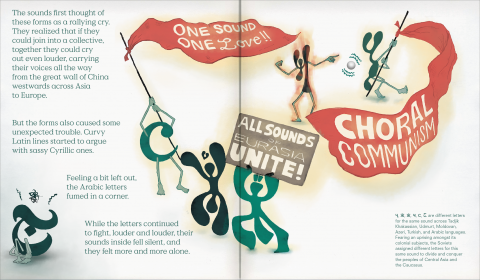

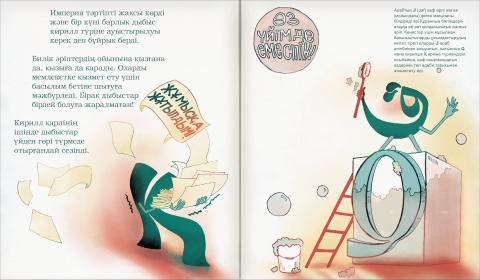

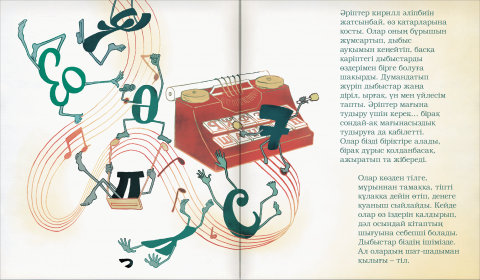

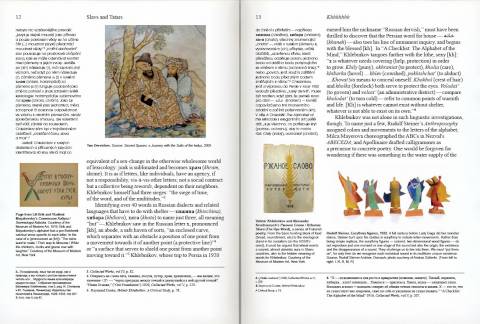

Azbuka Strikes Back

A mordant look at the constantly changing alphabets of 25 million people in the time of the Soviet Union. This interactive book offers a whirlwind tour of ABCs and anticolonialism in the former Soviet sphere.

Лук Бук (Look Book)

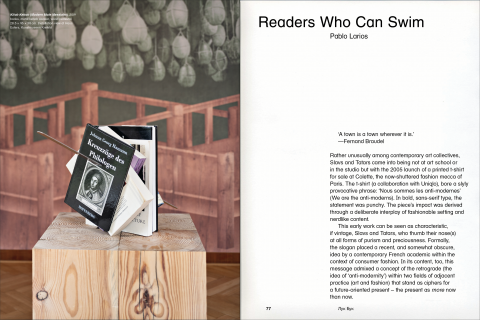

Published on the occasion of the exhibition, Лук Бук offers a comprehensive overview of Slavs and Tatars’ printed matter. Featuring essays by Pablo Larios and Dina Akhmadeeva, the catalogue demonstrates print’s unique ability to convey the conjunction of scholarly analysis, humor, and generosity of spirit that has become a trademark of the collective’s output.

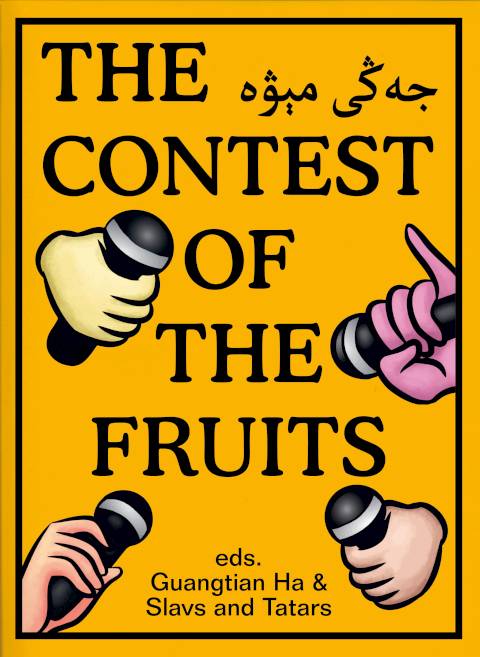

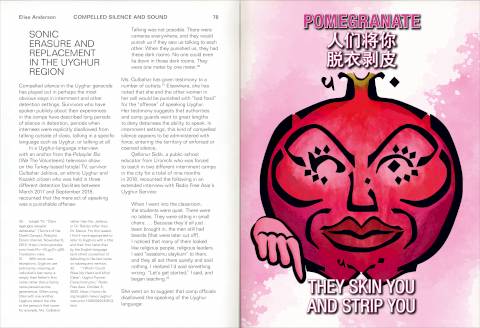

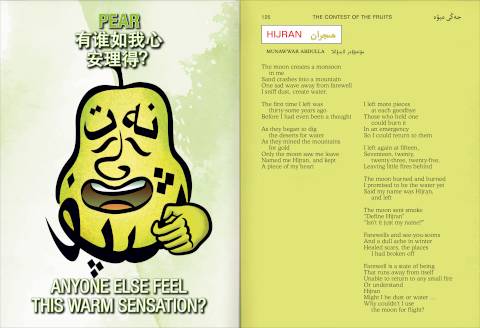

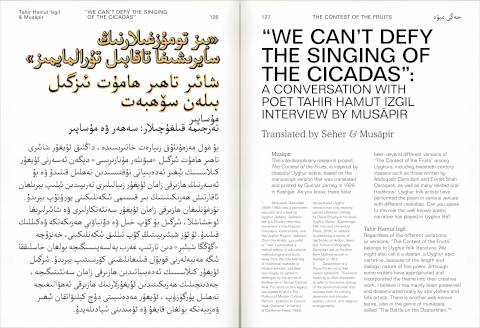

The Contest of the Fruits

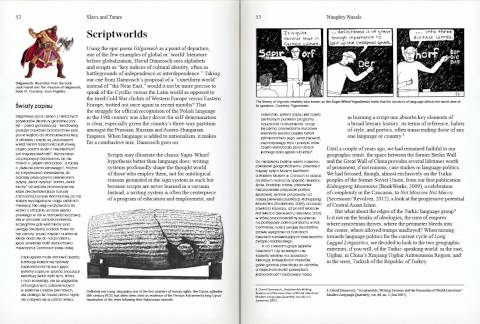

Co-published by MIT Press and Haverford College on the occasion of The Contest of the Fruits animation, the publication features essays by leading scholars and journalists that cover topics ranging from Uyghur script changes to rap in China, from silence to satire. Other contributions take a more tentacular approach: with a selection of poetry by diaspora Uyghur poets and insight on Chinese Muslim calligraphy, maintaining cultural heritage, the Sufi practice of Samā', mäshräp, and pop music.

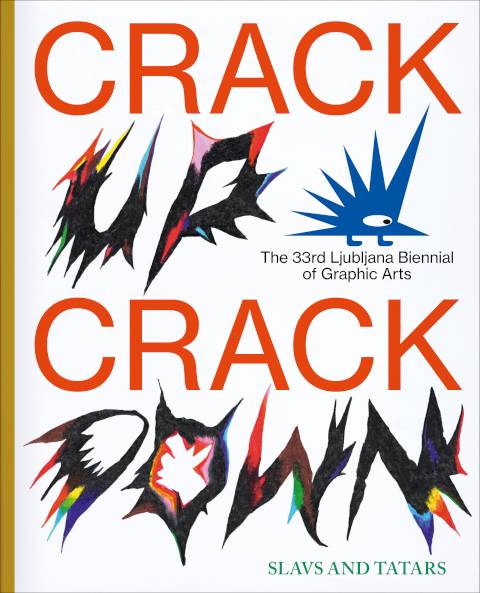

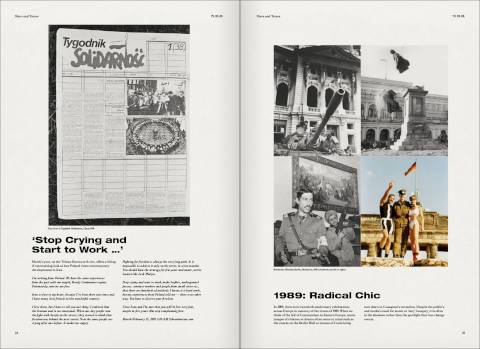

Crack Up – Crack Down

Edited by Slavs and Tatars and M. Constantine. Texts by Hamja Ahsan, Emily Apter, M. Constantine, David Crowley, Arthur Fournier & Raphael König, Augustin Maurs, Metahaven, Alenka Pirman & KULA, Mohammad Salemy, Vid Simoniti, Slavs and Tatars, Goran Vojnović.

As the accessibility of print brought about a proliferation of satirical periodicals in the early 20th century (Slovenia’s Pavliha, Germany’s Simplicissimus, the UK’s Punch, France’s l’Assiette au Beurre, or the Caucasus’ Molla Nasreddin to name a few), so too has the current digital age provided a particularly fertile avenue for satire, one which is fundamentally graphic, be it the meme or the protest poster. Though each enjoys a distinct history, both the graphic arts and satire claim to speak for and to the people.

Designed by Stan de Natris (Slavs and Tatars), illustrated by Nejc Prah, and published on the occasion of the 33rd edition of the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts, Crack Up – Crack Down considers “the graphic” heritage of the Biennial not as a medium, per se, but rather as an agency and strategy. Purporting to speak truth to power, satire has proven itself to be a petri dish in a world of post-truth bacteria. Edited by Slavs and Tatars, the exhibition’s curators, Crack Up – Crack Down extends the discursive focus of the Biennial on graphics and satire: featuring commissioned essays from Emily Apter on the micropolitics of memes, David Crowley on punk as a platform of dissimulation in Poland and Hungary, Vid Simoniti on the cult Bosnian satire Top lista nadrealista, among other Balkan precedents, and Melissa Constantine on the affective infrastructures of satire with visual contributions and essays by Metahaven, Hamja Ahsan, Alenka Pirman, and others.

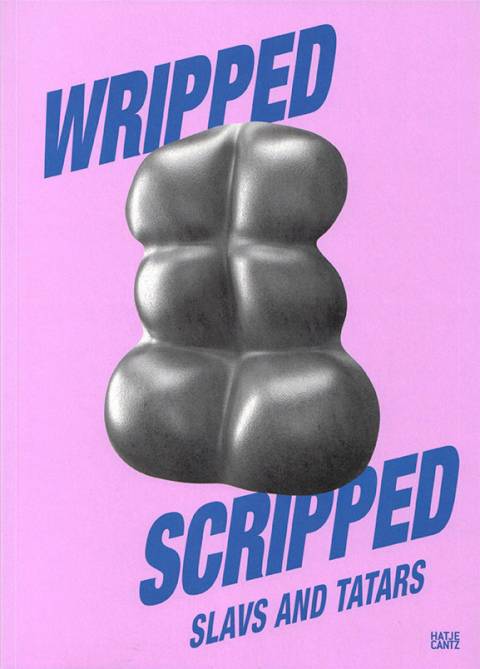

Wripped Scripped

Wripped Scripped continues Slavs and Tatars’ investigation of alphabets as an equally political and affective platform. The book includes an essay on gender fluidity in Hurufism, a 14th century Muslim science of letters as well as Germany’s relationship with Islam and Orientalism through the tetragraph [dsch].

Kirchgängerbanger

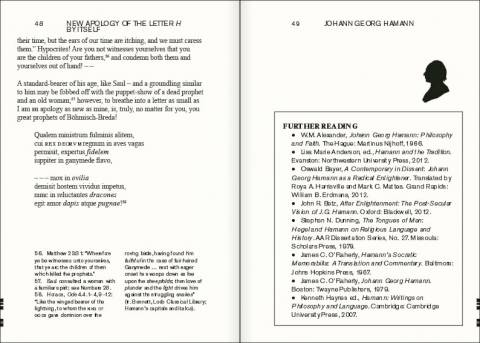

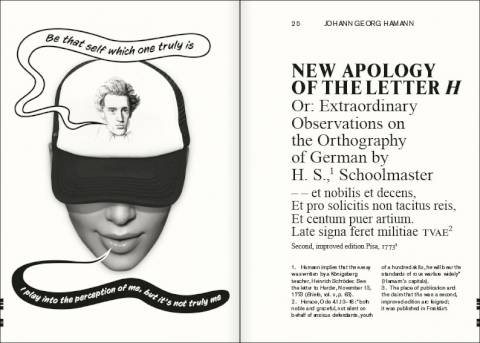

Kirchgängerbanger is a reader on Johann Georg Hamann, the 18th century polemicist, frenemy of Kant, and proto-Postmodernist who critiqued the Enlightenment with an unlikely mix of Lutheran theology and vulgar sexuality, enough to make even Bataille blush: “My coarse imagination has never been able to conceive of the creative spirit without genitalia.” With an introduction by Slavs and Tatars and a selection of essays by J.G. Hamann including the triple-platinum hits ‘New apology of the Letter H’ and ‘New Apology of the Letter H by Itself.’

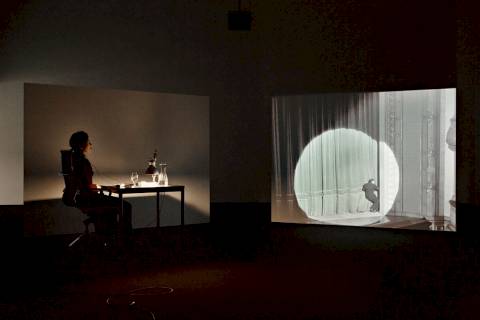

Slavs and Tatars (Mouth To Mouth)

On the occasion of a mid-career survey presented in Warsaw, Tehran, Istanbul and Vilnius, Mouth to Mouth is the first monograph on the collective, with documentation of all eight cycles of work. This monograph offers a critical inventory of Slavs and Tatars’ lecture-performances, exhibitions and publications across ten years of activity. Edited by Pablo Larios with essays by Susan Babaie, Jörg Haiser, and David Joselit.

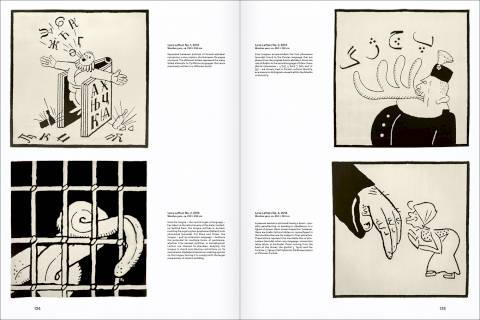

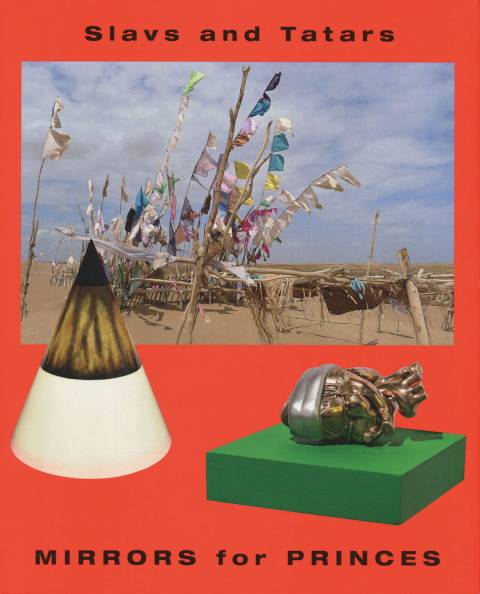

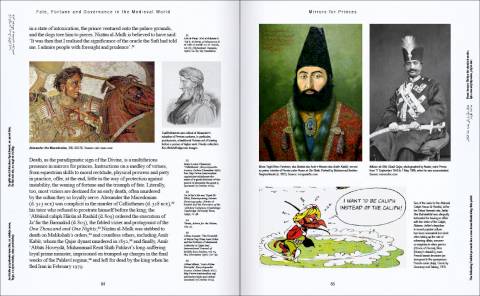

Mirrors for Princes

A form of political writing often called advice literature shared by Christian and Muslim lands, during the Middle Ages, mirrors for princes attempted to elevate statecraft (dawla) to the same level as faith/religion (din). These guides for future rulers – Machiavelli’s The Prince being a widely-known if later example – addressed the delicate balance between seclusion and society, spirit and state, echoes of which we continue to find in the US, Europe and the Middle East several centuries later.

Mirrors for Princes brings together the writing of pre-eminent scholars and commentators using the genre of medieval advice literature as a starting point to discuss contemporary politics in Turkey, Indian television dramas, fate, fortune and governance, and advice for female nobility.

The volume includes illustrated essays by David Crowley, Manan Ahmed, Anna della Subin, Neguin Yavari and Lloyd Ridgeon, and an interview with Slavs and Tatars by Anthony Downey and Beatrix Ruf.

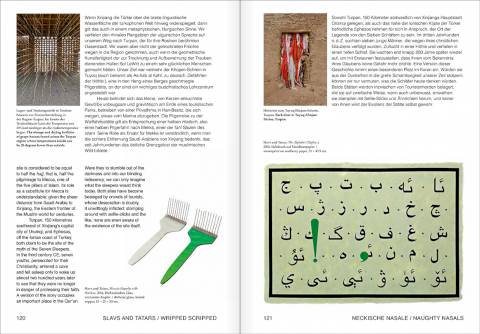

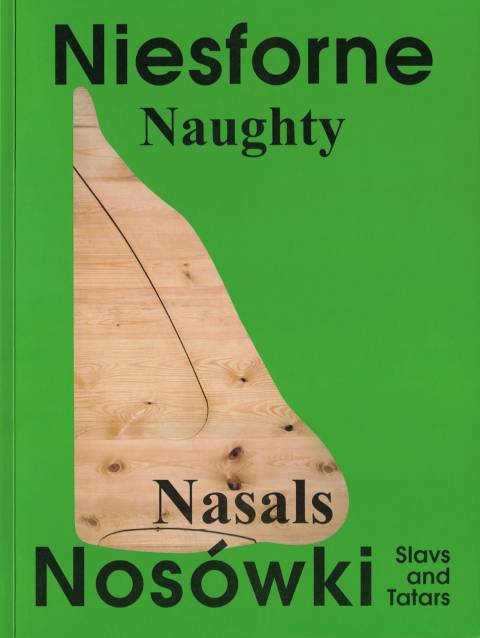

Naughty Nasals

“All the body parts used for language – the lips, neck/throat, nose, teeth, ears – are erogenous, sensuous, throbbing organs, receiving or giving pleasure. In order to escape the cold, clinical approach to linguistics and the hard hangover of language politics, we decided to seek warmth and refuge in the darker, carnal, or even cartilaginous, corners of language: more sybaritic than semantic.

We first tried to redress this imbalance with Khhhhhhh, a publication which passed over the tongue and the mouth in general, to see in the throat a phonetic source of sacred agency, be it in the Arabic Abjad, Hebrew Gematria, or Russian Futurism à la Khlebnikov. This time around, we indulge the proboscis and find in the nose a particular site of resistance in the Slavic and Turkic languages. The drive to Cyrillicize Polish hit rather steep speed bumps in the shape of the nasal vowels ą and ę. If Slavic languages ever had nasal sounds, most have since been lost, save for those in Polish and some instances of Bulgarian. […]”

Excerpt from the publication

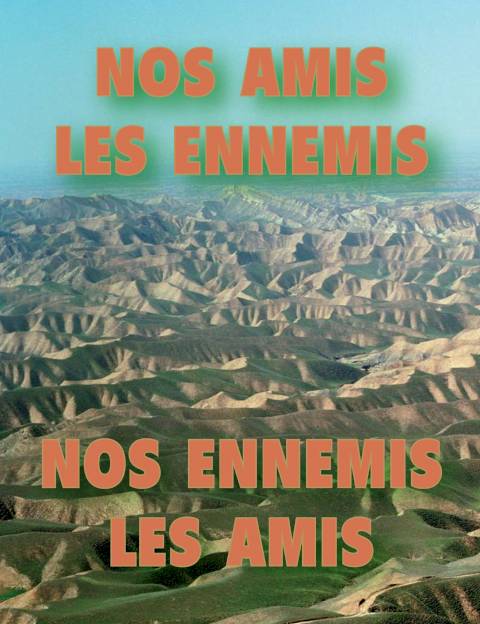

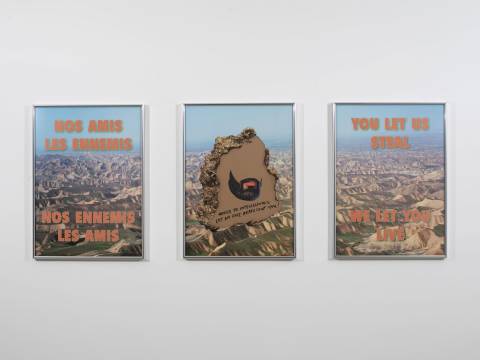

Friendship of Nations

Beginning as an investigation into the apparently disparate events that bookend the twentieth and twenty-first century – the collapse of Communism in 1989 and the Iranian Revolution of 1979 – Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz traces unlikely points of convergence in Iran and Poland’s economic, social political religious and cultural histories. Drawing on Slavs and Tatars’ multi-disciplinary practice encompassing research, installations, lecture-performances, and print media this publication embraces new contributions in the form of essays interviews and archival presentation on subjects that range from seventeenth-century Sarmatism to the twenty-first-century Green Movement taking in along the way tales of the Polish Exodus, Wojtek the bear, craft, hospitality, Passion plays and taziyeh, and the political lessons of a Polish slow burn revolution for contemporary Iran. The volume includes essays by Agata Araszkiewicz, Mara Goldwyn, Shiva Balaghi and Michael D. Kennedy, Slavs and Tatars and an interview between Ramin Jahanbegloo and Adam Michnik.

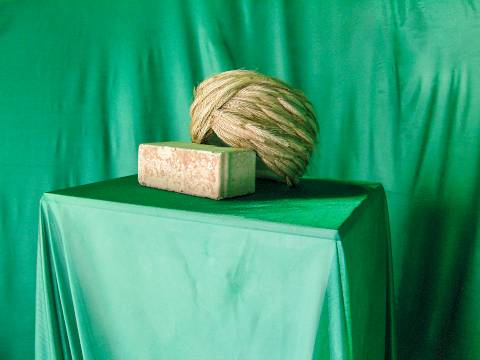

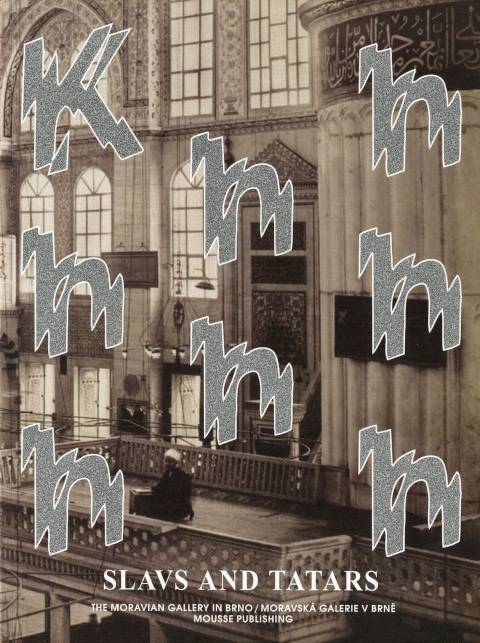

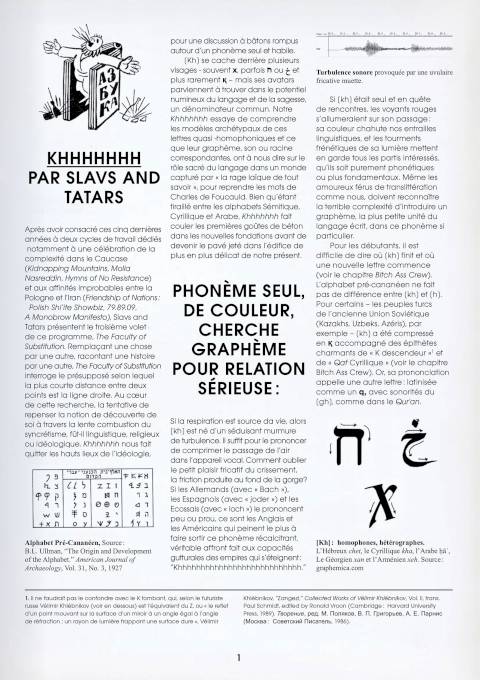

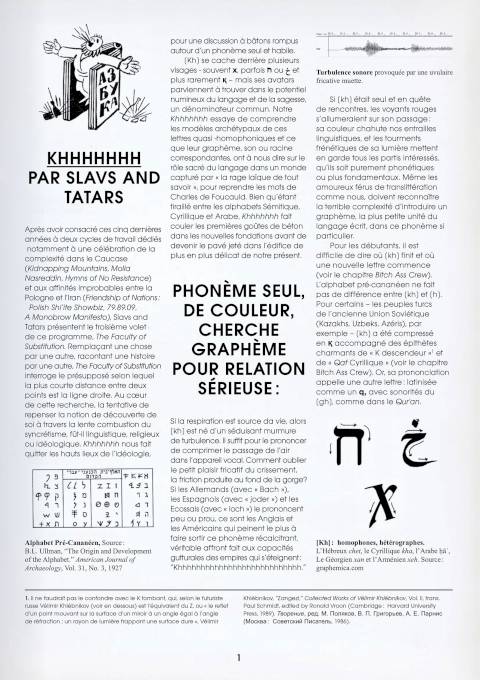

Khhhhhhh

“[Kh] goes by different names – sometimes x, other times ח or ﺥ, and on lesser known occasions, қ – but manages to put forth a common front on the numinous potential of language and wisdom. Our Khhhhhhh investigates the archetypal patterns of the aforementioned, quasi-homophonic letters, and what their corresponding grapheme, sound, or root have to say about the sacred role of language in a world beholden to a secular rage to know it all. Despite being tugged in different directions by the Semitic, Cyrillic, Turkic, and Arabic alphabets, Khhhhhhh pours the first drops of concrete into new foundations before becoming the brick thrown at the increasingly delicate edifice of the present. […]”

Excerpt from the publication

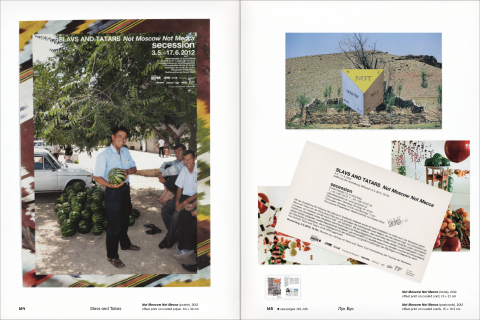

Not Moscow, Not Mecca

“Few people dare mention Marx and Mohammed in the same breath. For, what on earth (or in heaven, with or sans the 72 houris) could an atheistic economic and political philosophy have to do with a religion dedicated to the worship of the one and unique God? Does the former not continue to be the darling of leftists, who (like philandering partners, unwilling to make a clean break) keep coming back for one last chance, only to prolong the pain of all parties – while the latter takes pride in its traditionalist, some would say reactionary positions on a range of issues? Rare are the legs, but rarer yet are the heart and mind that can do splits. It is precisely such mental and mystical acrobatics that sweep us as Slavs and Tatars, not to mention Khazars, Bashkirs, Karakalpaks, and Uighurs, off our feet. […]’

Between the twin towers of communism and Islam lies a region alternatively called Ma wâra al nahr, Transoxiana, Greater Khorasan, Turkestan, or simply Central Asia. Like us, it too belongs to too many peoples and places at once, caught between Imperial Russia and Statist China, Chinggisid and Sharia laws, sedentary and nomadic tribes, Turkic, Persian, and Russian languages – not to mention Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic alphabets. As Maria Elisabeth Louw writes, ‘[t]he stubborn enchantedness of the world is perhaps most telling in the parts of the world where the concrete efforts to disenchant it were extraordinarily organized and profound.’ We turn to this ‘country beyond the river’ (Amu Darya, aka the Oxus) in an effort to research the potential for progressive agency in Islam. In a land considered historically instrumental in the development of the faith, but nonetheless marginalized in our oft-amnesiac era, its approach to pedagogy, to the sacred, and to modernity itself offers a much-needed model of critical thinking and commensurate being.”

Excerpt from the publication

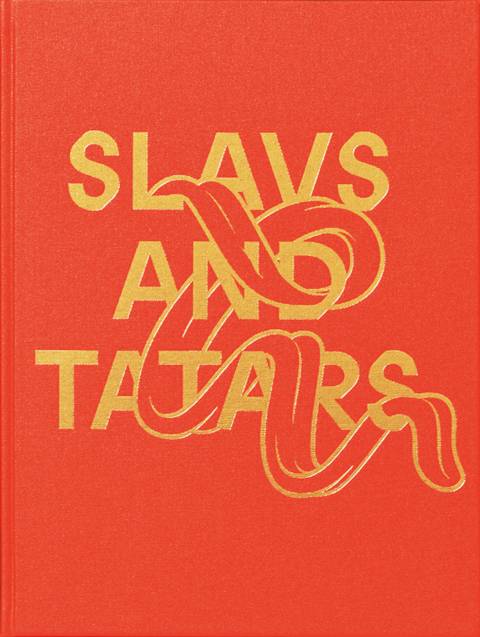

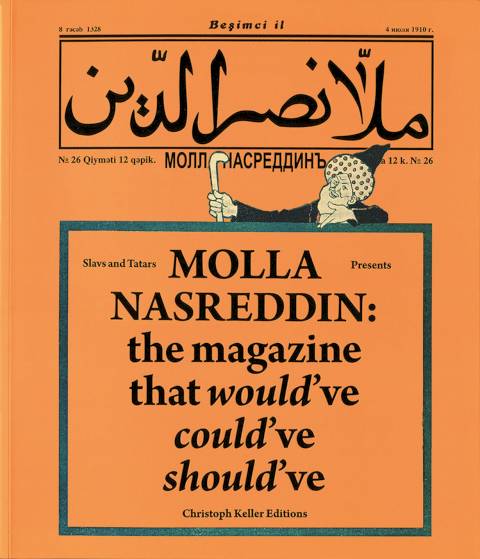

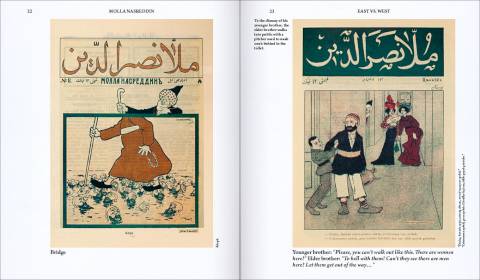

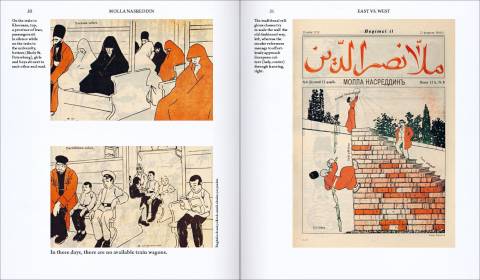

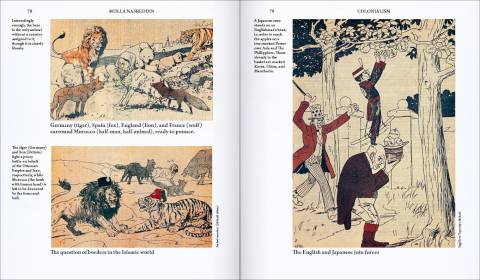

Molla Nasreddin

Published between 1906 and 1930, Molla Nasreddin was a satirical Azeri periodical edited by Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (1866–1932), and named after the legendary Sufi wise man-cum-fool of the Middle Ages. Thanks to its prominent use of caricatures, the weekly was arguably one of the most important 20th century periodicals of the Muslim world, read from Morocco to India. With an acerbic sense of humour and compelling, realist illustrations reminiscent of a Caucasian Honoré Daumier or František Kupka, Molla Nasreddin attacked the hypocrisy of the Muslim clergy, the colonial policies of the US and European nations towards the rest of the world, and the venal corruption of the local elite while arguing repeatedly and convincingly for Westernization, educational reform, and equal rights for women.

79.89.09

A transcript of Slavs and Tatars’ first lecture-performance, 79.89.09 revisits the book-ends of twentieth-century Communism and twenty-first century Islam, reimagining Polish/Iranian solidarity and exploring new lessons of the revolutions of 1979 and 1989.

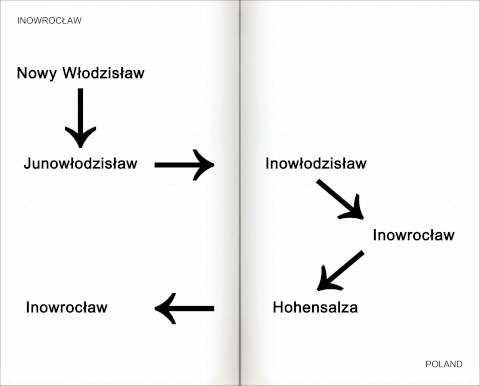

Love Me, Love Me Not

A selection of 150 cities within Slavs and Tatars’ Eurasian remit, Love Me, Love Me Not: Changed Names plucks the petals off the past to reveal an impossible thorny stem: a lineage of names changed by the course of the region’s grueling history. Some cities divulge a resolutely Asian or Muslim heritage, so often forgotten in some citizens’ quest, at all costs, for a European, Christian identity. Others vacillate almost painfully, and others with numbing repetition, entire metropolises caught like children in the spiteful back and forth of a custody battle. Love Me, Love Me Not celebrates the multilingual, carnivalesque complexity readily eclipsed today by nationalist struggles for simplicity and permanence. If, from the foggy perch of the early 21st century, we tend to see cities like living organisms that are born, grow and even die, why should their names be any different?

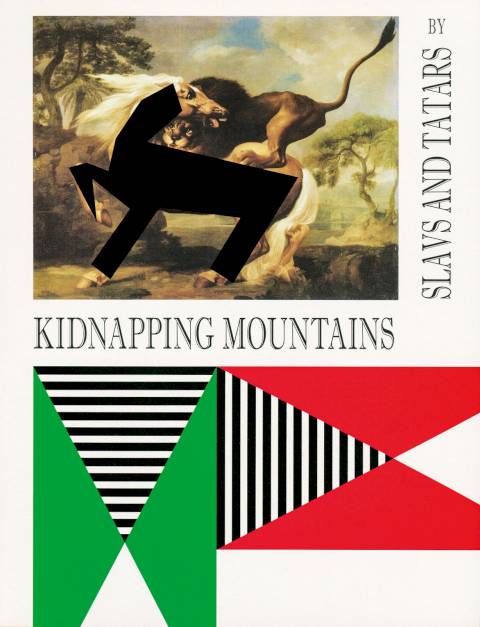

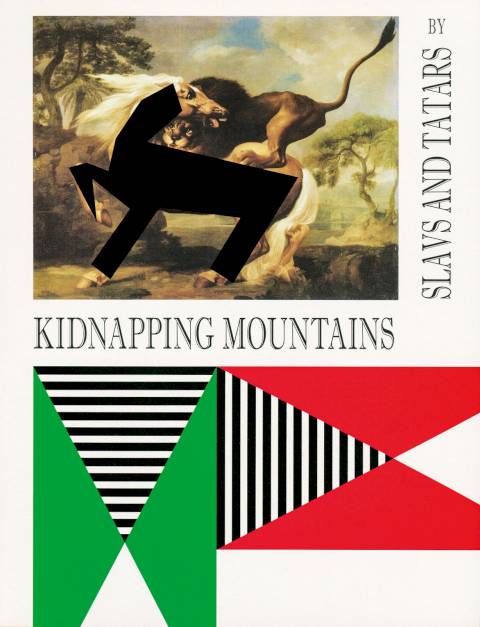

Kidnapping Mountains

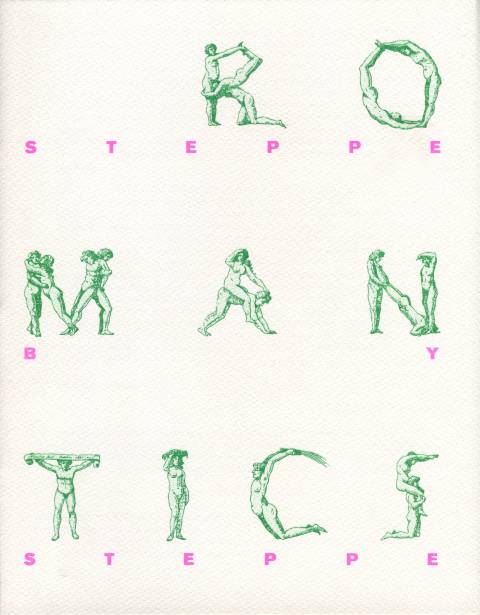

Kidnapping Mountains is a playful and informative exploration of the muscular stories, wills, and defeat inhabiting the Caucasus region. Comprising two parts: an eponymous section addressing the complexity of languages and identities on the fault line of Eurasia, and ‘Steppe by Steppe’, a restoration of the region's seemingly reactionary approaches to romance.

Live Streaming

False Friends

Self-Help

Open Mic

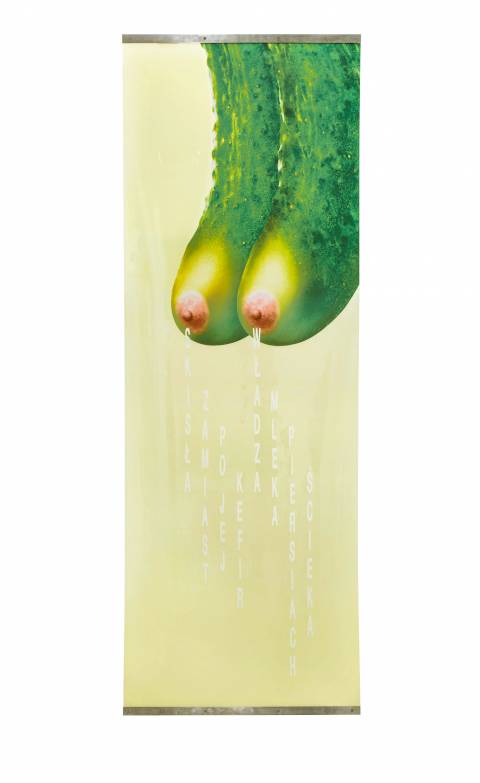

Via its prolific use as a shorthand for satire, humor and comedy, here the gherkin becomes a verb, an imperative, in the shape of an exclamation mark.

Sinophrys Salon

On the occasion of Pinakothek's acquisition and presentation of Hi, Brow! an edition celebrating the often-overlooked hairs in between our brows.

Figa

An obscene hand gesture specific to Turkic and Slavic cultures, Figa revisits the old Egyptian proverb: “Life is like a cucumber: one day in your hand and one day in your ass.”

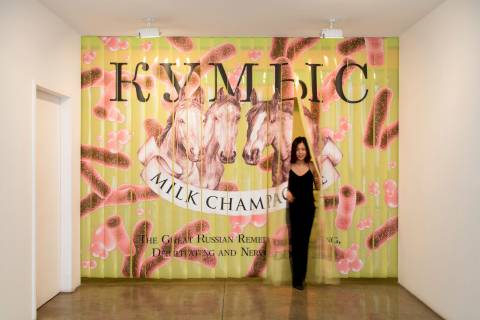

Steppe Momma’s Milk

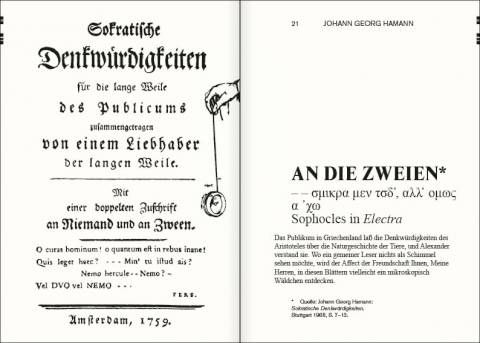

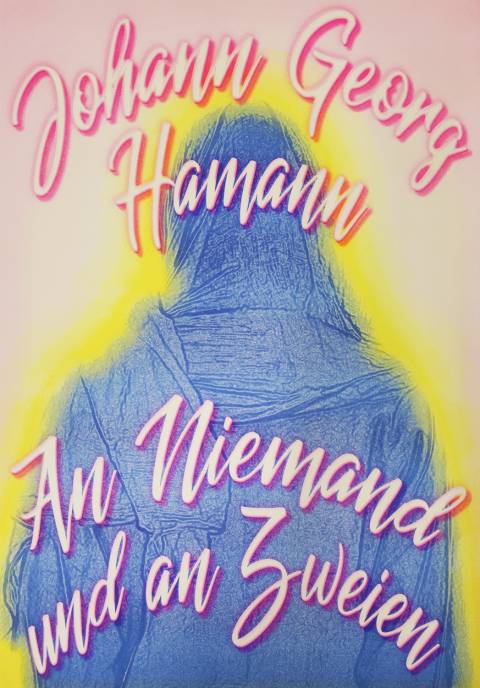

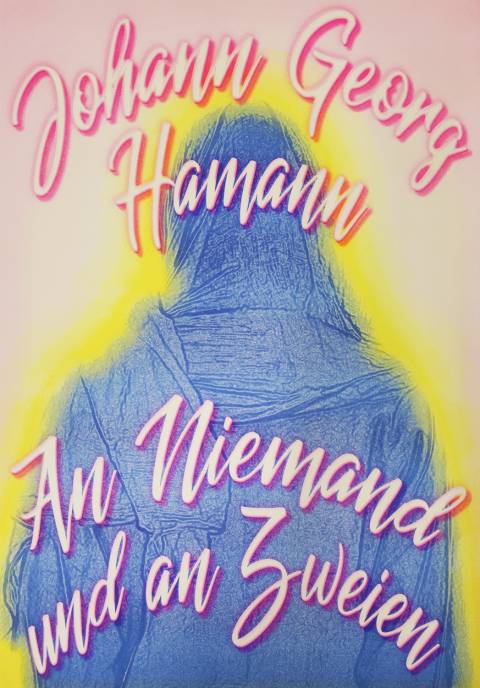

An Niemand / an Zweien

J.G. Hamann’s famous dedication – To Nobody and to Two – is an invitation to think beyond the binaries of Enlightenment thinking.

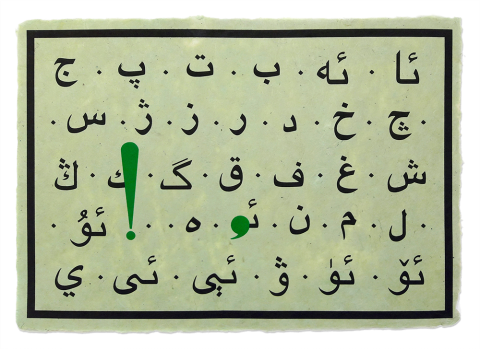

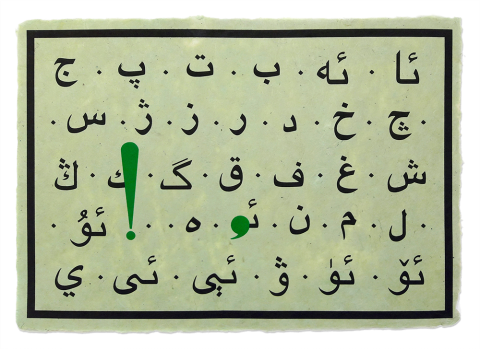

The Alphabet (Uighur)

Bicephalic

An Niemand

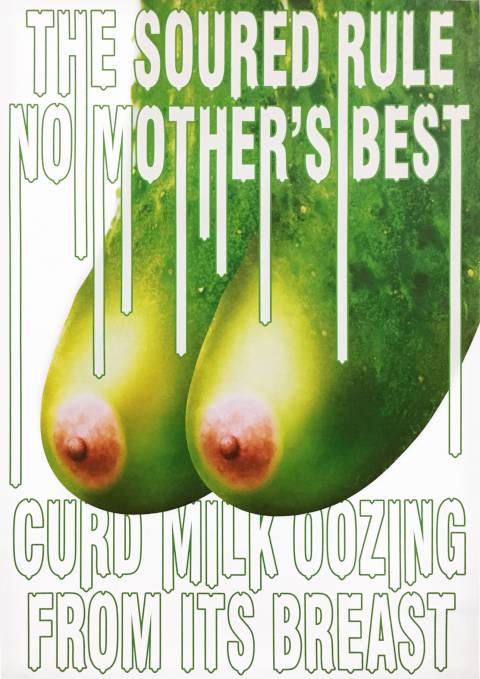

Pickle Tits

Beyond gustatory pleasure and digestive benefits, fermentation also offers an affective if ambiguous means to understand the rotting of our current social contract. The phenomenon of fermentation is at once destruction (decay), activation (probiotics), and transmogrification (a cucumber into a pickle). Instead of the nourishment often associated with patriarchal or matriarchal states, here the milk has soured to kefir tits.

Qabaret

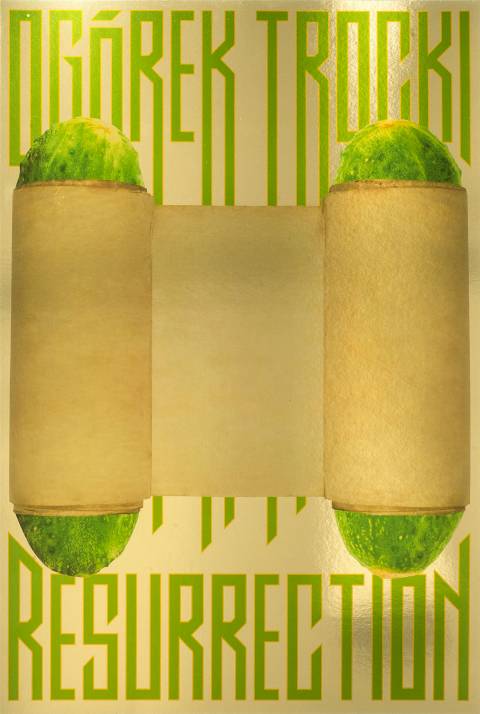

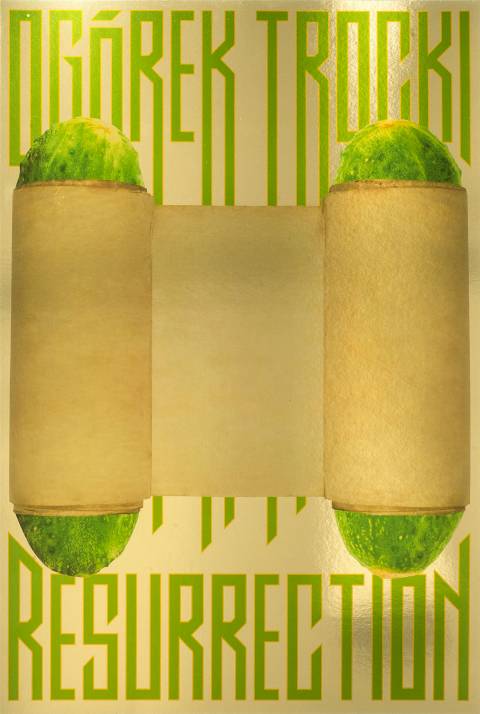

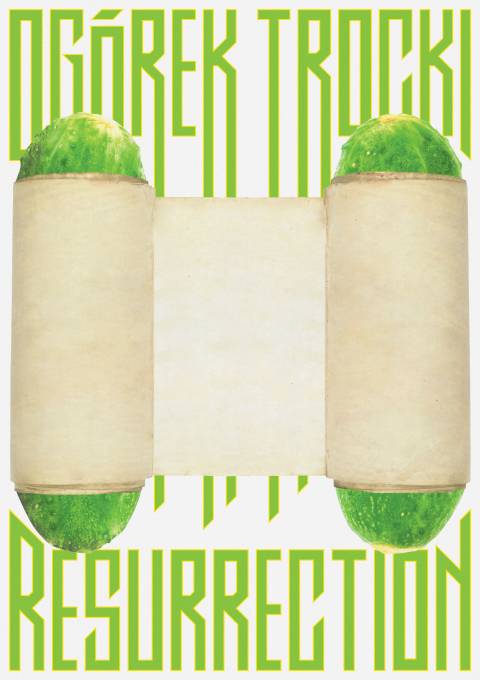

Ogórek Trocki

The Trakai cucumber, famed for its high sugar content, hails from the city of the same name in Lithuania. The specimen was brought to the Baltic countries and Poland by Crimean Karaites, an anti-rabbinical sect of Turkic-speaking Jews who first settled in the area in the late fourteenth century. Having spent more than a millennium living amongst majority Muslim populations, the Karaites have a remarkably syncretic if strict approach to faith: one finds basins for ablution outside their kenessas or synagogues; shoes must be removed before entering a place of prayer; the faith is passed on via patrilineal descent and not matrilineal as other Jews. During Islam’s golden age, between the 9th and 11th centuries, Karaites made up roughly 20-30% of the Jewish population. In the Crimea, though, Karaites had a particularly malleable approach to their own history. In the 19th century, Abraham Firkovich, a Crimean Karaite leader, convinced the tsar that they had settled in the area before the lifetime of Jesus Christ and thus were not responsible for his death. In 1863, the word ‘Jew’ was officially removed from documents belonging to members of Karaite community, sparing them taxes levied on Jews in Imperial Russia as well granting them the right to live outside the Pale, and thus avoid the regular pogroms. During the Nazi occupation of Crimea, Seraya Shapshal, the Karaite leader, convinced the Nazis that they were ethnic Turks, descendants of the Khazars, and thus they were spared the Holocaust. Though the Crimean Karaites survived two major persecutions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, sadly, the cucumber they were renowned for cultivating did not.

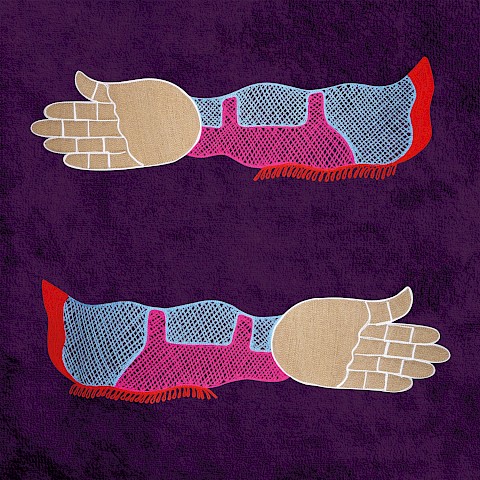

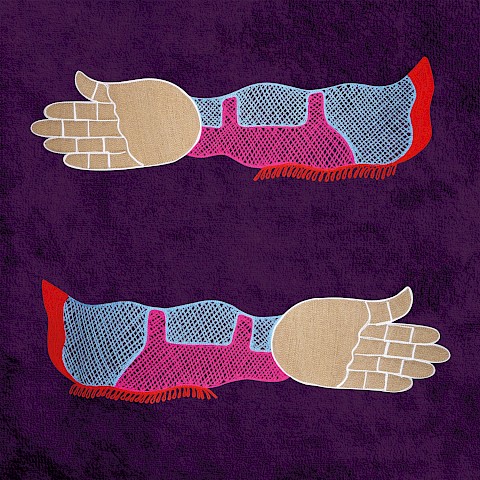

Larry Nixed, Trachea Trixed

Larry Nixed, Trachea Trixed looks at various attempts to Cyrillicize sounds or phonemes that did not previously exist in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet, one of many attempts to extend or embed Soviet influence, with a decidedly more sensuous, if not sexualized, approach to the traditionally cold, clinical approach of linguistics.

The Wizard of Öz Türkçe

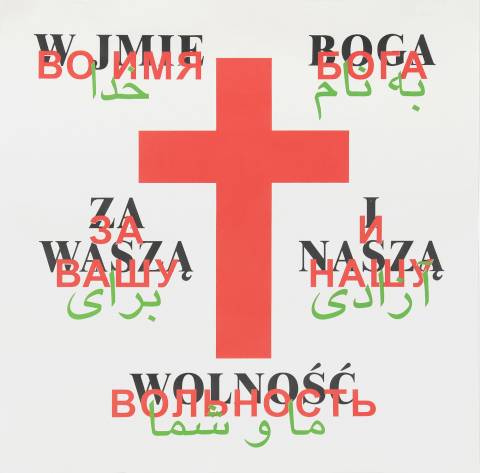

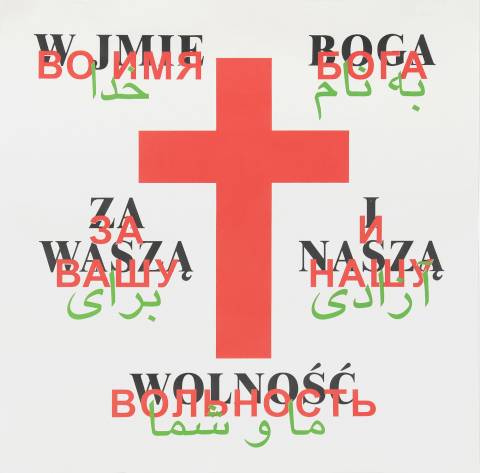

In the Name Of God

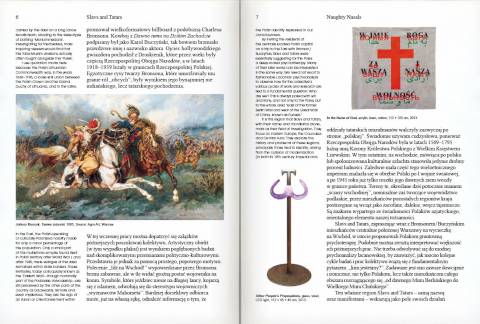

An unofficial motto ‘W imię Boga za Naszą i Waszą Wolność’ (In the Name of God, For Your Freedom and Ours) has been appropriated by peoples all around the world in their struggles for self-determination. Featuring both Russian and Polish in its original iteration, the banner is a complex nod to the fate binding two countries whose history has been contentious to say the least. By translating the original into Persian and re-instating the Russian, W Imię Boga addresses the transnational, if not transcendental, nature of this phrase, aiming to rescue it from the jaws of parochial or imperial instrumentalizations.

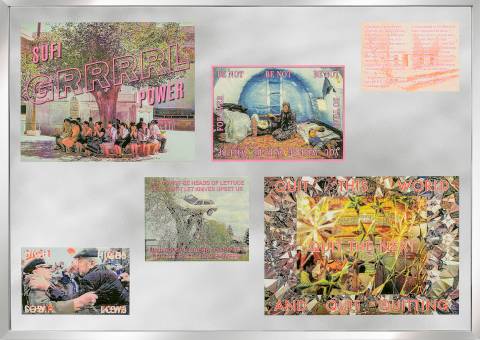

Behind Reason

A series of prints on the overlooked story of mysticism within modernity, made to accompany Beyonsense, Slavs and Tatars’ Projects 98 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Between 79.89.09

AaaaaaahhhhZERI!!!

During the editing process of Molla Nasreddin, we had a difficult time identifying a translator who could read all three iterations – Arabic, Latin and Cyrillic – of Azerbaijani and translate into English. AaaaaaahhhhZERI!!! is as much a scream for help as a tribute to the 20th century script changes of the alphabet. The poster speaks to the legacy of such language politics on the cultural heritage of Azerbaijan, effectively making different generations immigrants within their own language.

Steppe by steppe romantics

“By their very nature secret practices, being secret, are generally hard to comment on. Still, we can imagine that the institution of secret marriage must be at least as old as that of the public one, possibly older, in fact, if one is to imagine the birth of ‘coupledom’ as taking place between two people alone under the cover of night. Secret marriage today remains an incalculable part of the institution – and perhaps one of its most romantic forms. […]

As though to compensate, we celebrate the secret ceremony – gay, straight or non-binary – not with equal but greater fervour. Just as a stolen glance is more arousing, a forbidden tryst more urgent, so too is the secret marriage more alive, more keen. Marry in secret in solidarity, in lust, out of an exhaustive need. Marry in secret and do with the heart what the gun cannot: melt the frozen conflicts, be they in Abkhazia or in Glendale.”

Excerpt from the publication

League of Impatience

Last of the Eurasianists

As with many thorny ideas, Lev Gumilev’s Eurasianism has been hijacked, hacked, vulgarized. What was a critique of the Enlightenment underpinnings of Russia’s pivot to the West under Peter has today sadly become a shorthand for Russian nationalism. In that vein, to misquote Bono: “Charles Manson Alexander Dugin stole this song from The Beatles Lev Gumilev, we’re stealing it back.”

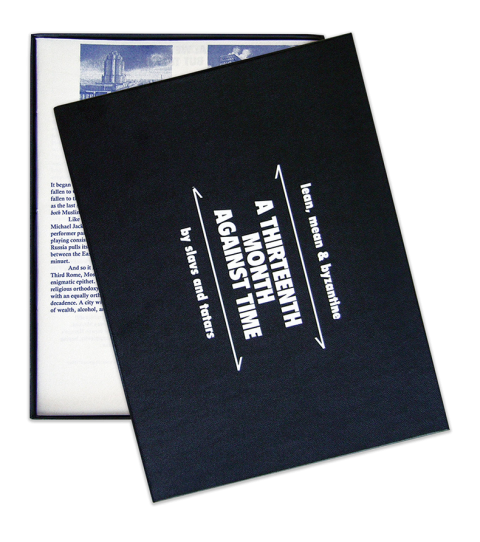

A Thirteenth Month Against Time

A libretto of daily polemics, reflections, and musings on the very defeatist approach to time so dear to S&T, A Thirteenth Month Against Time runs thirty-two days (or pages) in length and acts as an addendum to one’s everyday calendar or diary.

Drafting Defeat

We have always had an aesthetic weakness for the merciless and brutal banality of bureaucracy. Little did we know that such a weakness would extend to the bureaucrats themselves. The following are reproductions of 10th century maps – including Egypt, the Caspian, Iraq, amongst other places – by Al-Istakhri (aka Ibn Khordadbeh or Al Farsi) found in a 1933 Soviet edition of Nasser Khosrow’s Safarnameh, or Book of Travels. Both Istakhri and Khosrow were Persian bureaucrats whose legacy was a paper trail of the very antithesis of administration: a regime of curiosity that attempted to describe and map out the Middle East as a coherent geographic and cultural region. Khosrow, an 11th-century Persian poet and philosopher, had led an uneventful life as a tax collector in present day Turkmenistan when one night, in his sleep, a voice told him to leave behind his life of worldly pleasures. Khosrow dropped his avowed weakness for the medieval Merlot and began immediately to plan a seven-year trip through the Caucasus and the Caspian to the holy cities of Medina and Mecca. Khosrow was, to some extent, the millenary Muslim equivalent of a 21st-century born-again Christian. Except where the former asked questions, the latter offers only solutions. Where the former travelled extensively, the other is unlikely to have a passport.

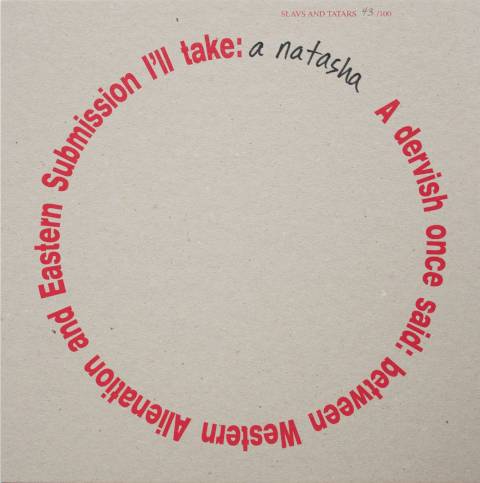

Slavs

The closest thing we have to a manifesto.

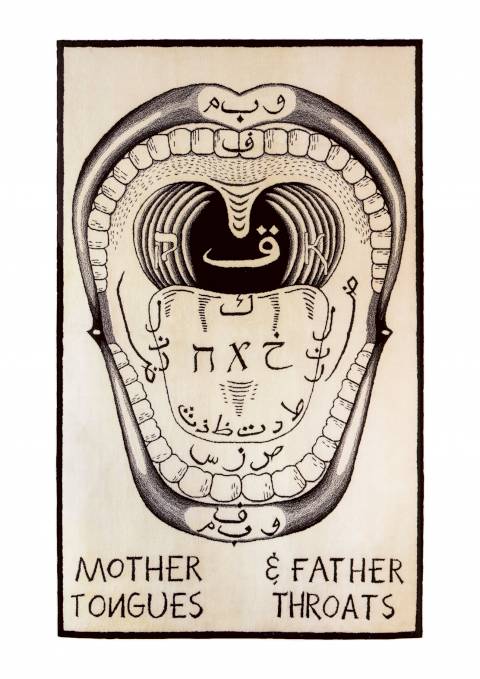

Mother Tongues and Father Throats

Limited to 50 units worldwide, Slavs and Tatars illustrated Havaianas’ signature Tradi Zori flip-flop. The design implemented on the footwear revolves around the ‘Mother Tongues and Father Throats’ artwork, created in reference to the throat being a source of mystical language.

Hi Brow!

Featuring an essay by Natasha Morris on the history of the monobrow, this fold-out poster was presented at the Pinakothek der Modern in 2021 to accompany the sculpture-performance of the same name.

Ritme Jaavdanegi

Album artwork for Mohammad Reza Mortazavi, a percussionist known for playing traditional Persian instruments such as the tombak and daf.

The Dark One

For the illy Art Collection, Slavs and Tatars present The Dark One, a homage to the geographic origins of coffee through a phonetic game. Three letters from three different alphabets almost magically reproduce the same guttural sound: “qaf”, the first letter of the original word for coffee in East Africa and the Arabian peninsula. The letters alternate to celebrate language and sensuality in a design that brings together geopolitics, food, & art.

Before the Before

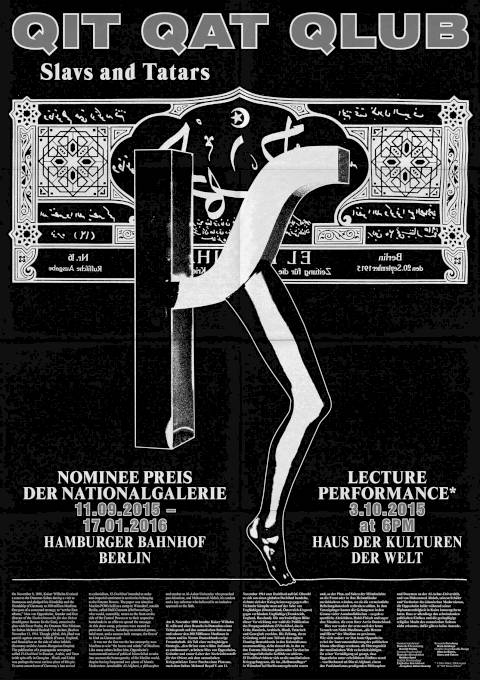

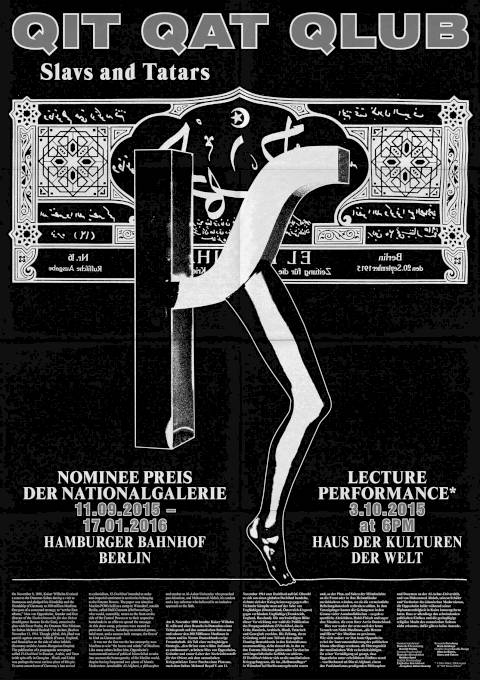

Qit Qat Qlub

Conceived for the Preis der Nationalgalerie 2015 exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof, a fold-out bilingual essay (English/German) and poster attempting to rescue German philology and its less than stellar secular origins.

Khhhhhhh (posters)

French: Printed on the occasion of Un Nouveau Festival at the Centre Pompidou in 2013.

Greek: Printed on the occasion of Long Legged Linguistics, a solo exhibition at the Art Space Pythagorion, Samos in 2013.

German: Printed on the occasion of Open House at the Kunstverein Braunschweig in 2015.

Korean: Printed on the occasion of The Voice at Coreana Museum of Art, Seoul in 2017.

Turkish: Printed on the occasion of Mouth to Mouth, Slavs and Tatars’ mid-career survey at SALT Galata, Istanbul in 2017.

Arabic: Printed on the occasion of Muʿawiya’s Thread at 32Bis, Tunis in 2023.

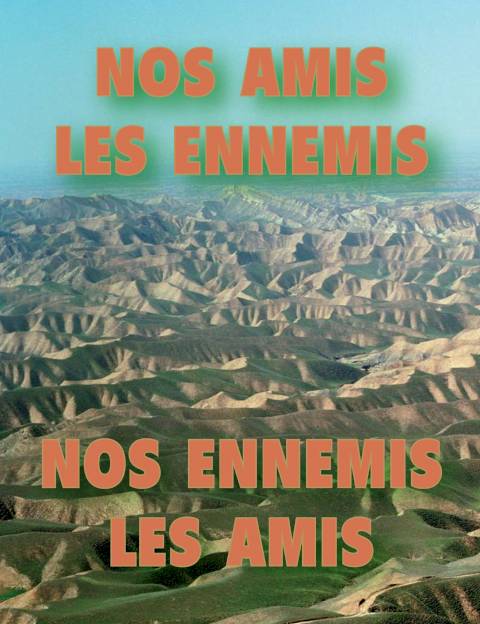

Nous Sommes Les Anti-Modernes

In Les Antimodernes, his study of 19th and 20th century French literary figures, Antoine Compagnon takes a contrarian approach to defining what makes a modernist. Instead of our highly processed diet of futurist heroes (think F.T. Marinetti or Vladimir Mayakovsky), who believed that science, speed, and industry would deliver us from our evil, backward ways, Compagnon offers a refreshing dose of the rear- or arrière-guard. The true modernist, he claims, has a conflicted relationship with the passing of the pre-modern era: s/he moves towards the future but keeps a watchful eye on the past. Examples include Joseph de Maistre, the Counter-Enlightenment philosopher who argued to reinstate the monarchy in the years following the French revolution; Charles Péguy, a poet and essayist whom both anti-Vichy and pro-Vichy camps claimed for themselves; and Baudelaire, whom Sartre described as driving into the future with an eye on the rearview mirror.

Our very languages betray us, at least the Indo-European ones. Along with the pox they brought the plague of positivism: be it French, Russian, Persian, or Polish. Our words describe the future as ahead of us, implying we can see where we are going. And the past is described as behind us, and thus somehow invisible or irrelevant. Thank God for the Malagasy, who seem to have got it right, for they describe the past as in front of us: taloha or teo aloha, and the future as behind us, aoriana or any aoriana.

Tranny Tease pour Marcel

First appearing in 2009 and one of the rare series which has continued throughout the duration of the collective’s practice, Slavs and Tatars’ iconic series Tranny Tease (pour Marcel) explore the alphabet politics behind the phenomenon of transliteration, particularly poignant in a region where millions of inhabitants have experienced if not three then two distinct changes of script in the past century. Each vacuum-formed panel uses the ‘wrong’ script for the language of the text.

Samovar

Taking the form of an oversized inflatable water boiler, teapot and serving tray lodged into the side of the Hayward Gallery, the sculpture is titled after the eponymous tea brewer commonly found across Central Asia.

A Russian invention of the mid-18th century, samovars are used today across Eastern Europe, the Middle East and some parts of Asia, in both domestic and communal settings.

Although humorously enlarged like a mascot or parade float, Slavs and Tatars’ installation uses the samovar as an emblem to recount the ways in which the history of tea is intertwined with cross-cultural exchange and colonialism.

By creating a monumental symbol of a celebrated and long-established tea culture, the artwork questions the role of tea in British history, tradition and popular culture.

Hi Brow!

A pocket mirror doubles as a chair in Hi, Brow!: a social sculpture and performance providing visitors the chance to receive a monobrow courtesy of a beautician.

Noblesse Oblige

Slavs and Tatars’ work often mixes registers of high and low, high-brow ideologies and low-brow media (pickles to balloons). In that vein, roasted sunflower seeds are a staple snack, shared across the Slavic-Turkic peoples from Eastern Europe to Central Asia. Like the wheat of Wheat Mollah, the sunflower seed becomes a symbol of proletariat or rather, its 21st century sucessor, the précariat.

Hamdami

Characteristic of the artists’ interest in coincidentia oppositorum (the coincidence of opposites) equally as a strategy as subject matter, Hamdami explores the conspiration of the sensual and spiritual.

RiverBed

The takht (bed, or what we call a ‘RiverBed’ in honour of its ideal location by a source of water), the vernacular structure found at teahouses, roadside kiosks, shrines, entrances to mosques and restaurants across Iran and Central Asia, accommodates a group of roughly four or five people without the unfortunate and unspoken delineation of individual space dictated by the chair. Friends, families, and colleagues sit, smoke shisha, sip tea, eat lunch, take naps, and create – however momentarily – a sense of public space, all the more remarkable in countries where public space is circumscribed, such as Iran.

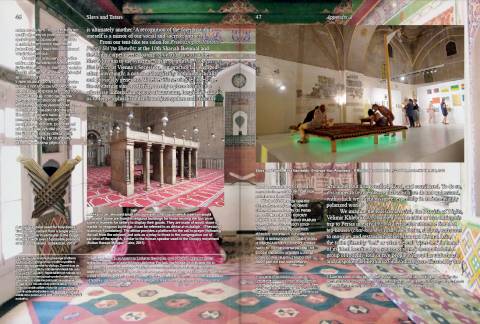

Reading Rooms

The book is central to Slavs and Tatars’ practice. In addition to an extensive publishing practice, the artists create spaces, sculptures, lecture-performances, installations and audio works all of which ostensibly bring us back to the book. For most of its history, though, reading has been a collective practice, not a private one. You could say the private or individual book as such is really only about 150 years old. Slavs and Tatars are committed to re-activating the idea of collective reading: not necessarily in the lteral sense of reading together, but rather in an attempt to create a multiple subjectivity, to read as a body of multiples. Above is a selection of various reading spaces within their exhibitions.

Kitab Kebab

A traditional kebab skewer pierces through a selection of Slavs and Tatars’ books, suggesting not only an analytical but also an affective and digestive relationship to text. The mashed-up reading list proposes a lateral or transversal approach to knowledge, an attempt to combine the depth of the more traditionally-inclined vertical forms of knowledge with the range of the horizontal.

Love Me, Love Me Not

A genealogy of a given city’s name changes, the result of rising or falling empires, states, and/or populations. Some cities divulge a resolutely Asian or Muslim heritage, so often forgotten in some citizens’ quest, at all costs, for a European, Christian identity. Others vacillate almost painfully, and others with numbing repetition, entire metropolises caught like children in the spiteful back and forth of a custody battle. Like much of Slavs and Tatars’ work, Love Me Love Me Not was first conceived as a book, a compilation of 150 such city names.

PrayWay

A collision of the sacred and the profane – the rahlé, the traditional book stand used for holy books, and the takht (or river-bed), vernacular seating areas used in tea-salons – PrayWay is part installation, part sculpture, part seating area, and all polemical platform.

Molla Nasreddin the antimodern

Often depicted riding backwards on his donkey, Nasreddin is a transnational folk figure found in different guises and under various names from Morocco to Croatia, Sudan to China. Using first-degree humour to question issues of morality and ethics, he has become a retro-active mascot of sorts for Slavs and Tatars. In Molla Nasreddin the antimodern the artists have given the old dervish a bounce to his step and made extra room for a sidekick. Children hold on tight to Hodja’s portly belly as this Sufi super-hero faces the past but trots into the future, cutting a profile of an anti-modern figure.

Nations

Whether it’s gender politics as geo-politics, migrant labor, or jadidism, to name a few, Nations employ bawdy humour and deliberate one-liners to deliver ice-breakers of unassuming density.

Régions d’être

“Despite their specifically-defined geographical remit, and commitment to this particular region, in some ways ‘Eurasia’ (the continental span that includes Asia, the Middle East, and Europe) is a foil: allowing viewers and audiences to consider their own relationships to more general questions of belonging, foreignness, citizenry, and to the multiple subjectivities that dwell, rightfully yet often with conflict, within any single place. This characteristic attention and care, deployed with humour, is tied to the collective’s transregional perspective: their understanding that any single place or person is in fact made up of many, and that the specific bleeds into the general. If the region of Eurasia is a deliberately broad net to cast, then without any instrumentalization, Slavs and Tatars find, accumulate, and re-present bodies of knowledge and material histories that can seem (to some) minute, niche, and arcane. This characteristic straddling of materiality and ideology, history and belief, the particular and the absolute” is a tension maintained within the jungle-gym of Régions d’être.

Excerpt from Slavs and Tatars, ed. by Pablo Larios, published by König Books, 2017

When in Rome

A deliberate slippage of terminology allows for a moment that is equally commemorative and confused. Coins are offered, not for beggars, but for believers as is often found strewn across icons of Orthodox Christianity. If modernity is the totalizing project of the 20th century, one that doesn’t allow for failure, one where expediency trumps reflection, perhaps Roma offer the possibility of escape, from the tyranny of the past and present.

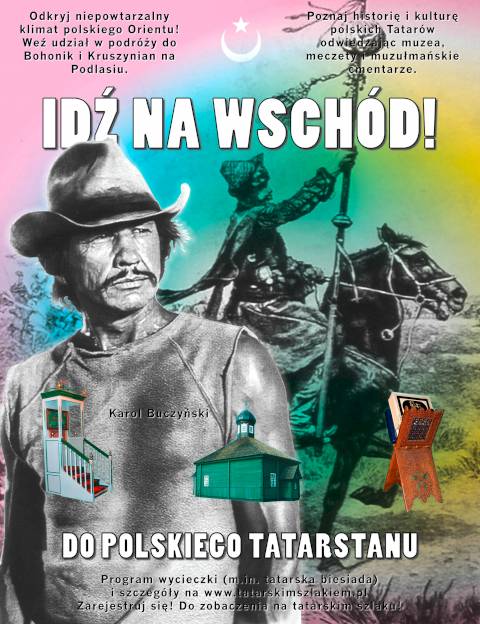

Idź na Wschód!

In 2009, Slavs and Tatars organized a day trip to Bohoniki and Kruszyniany, two Tatar villages in Poland, located near the Byelorussian border, which offer a cosmopolitan understanding of Polish identity and an ideal model of progressive Islam via the creolized vernacular architecture of the wooden mosques and the liberal relationship between men and women. In the Wola district of Warsaw, a billboard inviting people to ‘Go East’ featured Charles Bronson, né Karol Buczynski, of Once Upon a Time in the West fame, whose cheekbones and eyes were often mistaken for Mexican or Native American but were in fact a remnant of his Lipka Tatar heritage.

Histoire du Monde Slave et Tatar

Histoire du Monde Slave et Tatar proposes a revision of Louis-Henri Fournet’s famous Tableau Synoptique de l’Histoire du Monde, literally a visual diagram of the past 5000 years (or fifty centuries) of world history, to mark those regions falling within the artists’ geographic remit.

A celebration of complexity in the Caucasus, this cycle investigates the linguistic, social and political phenomena of a region at the site of historical crossroads between Ottoman, Persian and Russian empires.

To Mountain Minorities

The original Georgian expression ‘Chven Sakartvelos Gaumardjos’ is roughly translated as ‘Long Live Georgia!’ or ‘Vive la Georgie!’. By changing a single letter, however, the ‘a’ of ‘Sakartvelos’ to a ‘u’ to make ‘Sakurtvelos’, the phrase becomes ‘Long Live Kurdistan!’ and the unresolved geopolitical identity of one mountain peoples is replaced with that of another.

Mountains of Wit

Горе от Ума (Gore ot Uma, meaning ‘woe from wit’) is a famous 19th century play about Moscow manners by Aleksander Griboyedov, a close friend of Pushkin’s and diplomat to the Tsar in the Caucasus. By changing the ‘e’ in the original Russian title to an ‘Ы’, a quintessentially Russian letter, the title becomes Mountains of Wit, and the urban premise of the original work is hijacked by a Caucasian setting equally imaginative and apposite, one which played an influential role in Griboyedov’s life and death.

Hymns of No Resistance

Hymns of No Resistance features classic and cult pop songs revised to address issues of territorial dispute, language, and geopolitics within greater Eurasia. An adaptation of Michael Sembello’s Flashdance track ‘She’s a Maniac’ becomes ‘She’s Armenian’, replacing the struggles of an aspiring dancer with those of a diaspora Armenian. Meanwhile, ‘Young Kurds’ – a retelling of Rod Stewart’s ‘Young Turks’ – tells the story of Sherko and Shirin, a Kurdish couple on the run. ‘Stuck in Ossetia with You’ (originally ‘Stuck in the Middle with You’ by Stealers Wheel) looks at the 2008 Russo-Georgian war.

Letter to Abriskil aka Amiran aka Prometheus

For the West, it was Prometheus who stole fire from Zeus and gave it to the mortals, and whose punishment was to be chained to a mountain (which happened to be in the Caucasus), with his liver eternally torn out by the beak of an eagle.

For the Ossetians, it was Amiran aka Abriskil who, according to legend, got into a rock-throwing match with Jesus. After an enormous boulder hurled past Jesus and lodged itself deep into a mountain, Jesus challenged Amiran to unearth the rock. Amiran did not succeed, and as punishment was chained to the peak of Mt. Kazbek. Amiran was a repeat offender, to use the revanchist legal lingo of his foe’s fanboys (i.e. Republicans): the son of a sorcerer, he singled out Christians for punishment. To this day, it is said that Amiran's despair and struggle to break free of his chains is what causes the avalanches and earthquakes in the greater region.

Kidnapping Mountains (Over-Here)

Given the density of different ethnic groups and languages in the Caucasus, sometimes from disparate language families, Kidnap Over-Here argues for a pre-modern understanding of identity, one which is spatially-inflected. For example, the Georgians living west of the Likhi mountain range, considered by some to be the natural border between Europe and Asia, refer to themselves as the “over-here’s” and to those living on the east side of the range as the “over-there’s”.

Dig The Booty

Dig the Booty features a transliteration of an aphorism across the Latin, Cyrillic and and Perso-Arabic scripts in homage to the vicissitudes of the Azeri alphabet which changed 3 times over the past century: from Arabic to Latin in 1929, from Latin to Cyrillic in 1939, only to go back to Latin in 1991.

The cycle began with a study of unexpected points of commonality between the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and Poland’s Solidarność movement of the 1980s, events that coincided with major geopolitical shifts in the twentieth century, resulting in the emergence of revolutionary Islam on the one hand, and the fall of communism on the other. The points of convergence between Poland and Iran’s respective quests for self-determination extend to 17th century Sarmatism, an exodus of Polish refugees to Iran during World War II, and the intermingling of faith and citizen diplomacy.

Communion

A series of reverse-glass paintings exploring the overlaps between Catholic and Sh’ia theology and iconography.

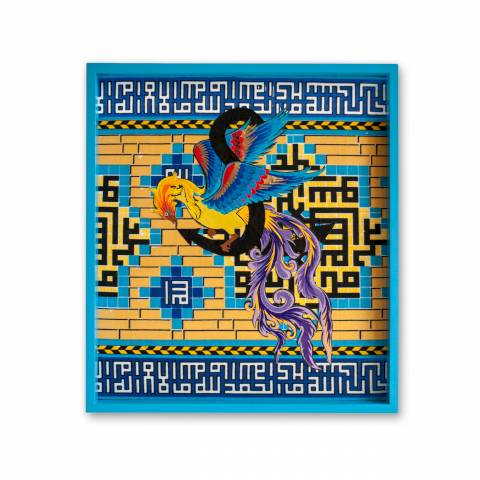

Inrising

Just as the anti-communist Solidarność Walcząca used the royal eagle, banned from official Polish insignia during communist rule, as an act of defiance to martial law, Inrising looks to the simorgh, the mythical Persian bird and Sufi symbol as a sign of solidarity, albeit in a less socio-economic and more mystical understanding of the term. The simorgh figures heavily in literary works such as Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and Attar’s Conference of the Birds: here the literary trope has been translated into a Polish craft technique of intricate paper cut-outs known as wycinanki.

Samizabt

Featuring a translation of Czesław Miłosz’s ‘Który skrzywdziłeś’ (You Who Wronged) into Persian, the sound work Samizabt (2013) speaks to the role of poetry as a form of political resistance. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from tsarist Russia to communist Poland, poets were considered a threat to the state, a stark contrast to their esoteric if not marginal role in Western nations. Following protests in Iran over the results of the 2009 presidential elections, works of Polish authors hitherto untranslated began to pop up in Tehran’s bookstores in Persian. Whether it was the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, philosopher Leszek Kołakowski, or poet Wisława Szymborska, the new crop of a particular nation’s literature makes a convincing case for early twenty-first century Iran to look to Poland’s late twentieth-century struggle with communism. Solidarność’s turn to religion and faith for its progressive potential and effective means of resistance, especially in the face of the creeping secular materialism left unchecked after the fall of the Iron Curtain, resonated with an opposition movement in Iran trying to triangulate between political Islam and the desire for a truly representative government.

In the Name of God

An unofficial motto of Poland, ‘W imię Boga za Naszą i Waszą Wolność’ (In the Name of God, For Your Freedom and Ours) has been appropriated by peoples all around the world in their struggles for self-determination. Featuring both Russian and Polish in its original iteration, the poster is a complex nod to the fate binding two countries whose history has been contentious to say the least. By translating the original into Persian and reinstating the Russian, In the Name of God addresses the transnational, if not transcendental, nature of this phrase, aiming to rescue it from the jaws of parochial or imperial instrumentalization.

Mystical Protest

Mystical Protest looks at the numinous, or the holy, as a potential agent for change in the concrete, material world. Muharram is the first month of the Islamic calendar and the second holiest month, following Ramadan. Each year, during the month of Muharram, Shi’ites re-enact various rituals and rites surrounding the death of Hussein Ibn Ali, the Prophet’s Mohammed’s grandson. A text reading “It is of utmost importance that we repeat our mistakes as a reminder to future generations of the depths of our stupidity” offers a defeatist admonishment to revolutionary calls for change.

Solidarność Pająk Studies

Originally a pagan tradition, the pająk (lit. ‘spider’ in Polish) was traditionally hung from the homes of rural Poles to celebrate the harvest and to bless the upcoming year of crops. Crafted according to local customs, they are often made with found, ephemeral materials. Slavs and Tatars revisit the pająk as a testimony to the painstaking diligence and delicate nature of compromise crucial to the Polish precedent of civil disobedience. Solidarność Pająk study 1-9 creolizes the pająk by integrating elements or motifs of Iranian Shi’a culture into an originally pantheist then Catholic-Polish one. In one, flowers are replaced with the wool bangles habitually adorning Persian carpets; in another, the reeds form the outline of the Allah crest of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Like the mirror mosaics of Resist Resisting God, the pająk is an example of craft as a vehicle for revolutionary critique and ideology.

Study for Sarmat Surfaces

One of the more surprising convergences in our studies of Iran and Poland has been the visual culture and craft traditions of their dominant faiths: Shi’a Islam and Catholicism, respectively. These range from passion plays and re-enactions of the Stations of the Cross to Ta’zieh, Carnival floats, Muharram alam, as well as banners and reverse-glass painting. Upending traditional notions of Renaissance perspective, painting behind glass requires beginning with the outermost layer, say the eyes, and moving inwards towards the background.

In Friendship of Nations, we often turned to crafts for their ability to decouple innovation from individuality. When push comes to shove, unlike the arts, crafts tend to opt for repetition over difference: an apprentice calligrapher for example, must spend some ten years copying his or her mentor before daring to attempt a flourish of their own. Such an approach allows us to consider innovation not as a series of ruptures or patricides, as the avant-garde would have us believe, but rather as a continuous process. Repetition – be it the mantra of a zikr or the stitching of a needlework piece – revolves around a certain genealogical transparency so engrossing that it verges on transubstantiation; one must not just reveal one’s sources but become them.

Wheat Mollah

A nod to the often-overlooked leftist origins of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. From the basic building block of food – bread – to the ideological stand-in for socialism, it could be argued that wheat emits a sacred, almost atavistic aura, and not just in Slavic countries. Established in 1925, Bank Sepah, Iran’s first bank, today sports a logo combining the stylized lettering for ‘Allah’, as found on the flag of the Islamic Republic, surrounded by a wreath of tulips on the left and a stalk of wheat on the right. This inadvertent tribute to the crest of the USSR, whose hammer and sickle are surrounded by two stalks of wheat, would make Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, the inheritors of the Army Pension Fund at the origin of Bank Sepah, drop their collective jaws. Add to wheat's impressive arsenal a talismanic quality: how else to explain that wheat has that rare ability to combine the seemingly incommensurate: communism and political Islam?

Friendship of Nations

Made accordingly by Polish seamstresses or Iranian tailors, the Friendship of Nations banners comprise the main body of work of the eponymous cycle. Creolizing best-practices from the Solidarność movement and the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the banners also speak to the unlikely points of resonance between craft traditions of the Catholic faith and Shi'a Islam.

Pre-Write Your History

On the occasion of the exhibition-cum-summer academy “Group Affinity” at the Kunstverein München, Slavs and Tatars looked into the notion of the anti-modern from craft traditions to female prayer rituals, including the Slavic harvest festival of dozhinki found across Eastern Europe.

Weeping Window (Chłopaki)

Using the rear window of a Polski Fiat 126, a legendary car manufactured in communist Poland, Weeping Window (chłopaki) features the antimodernist trope – looking backwards at history but moving forwards towards the future – that has become a trademark of sorts of Slavs and Tatars’ practice. From Sartre’s description of Baudelaire as driving forward but with an eye on the rear-view mirror, to Walter Benjamin’s ‘Angel of History’ propelled to the future but facing the rubble of the past, the anti-modern is perhaps best exemplified by Molla Nasreddin, the twelfth-century wise man-cum-fool often depicted riding backward on his donkey. The text – ‘Khajda Khłopaki’ – roughly translates as ‘Let’s go, boys!’ in an archaic Polish, an exhortation to advance forward despite glancing backwards.

A Monobrow Manifesto

Sometimes we must ask stupid questions of otherwise smart subject matter. As a cultural prism or epiphenomenon, the monobrow does just that: the pesky hairs that grow between the eyebrows have a startling way of distinguishing the West from the rest. In Victorian England, the monobrow was associated with delinquent behaviour; in eighteenth- and nineteenth- century French literature, a monosourcil incurred suspicion of being a werewolf; in the US today, it diminishes a child’s social capital in the cruel Darwinism called school. But other skies tell other stories: in Qajar paintings, the monobrow is brandished equally by both sexes. In Iran, it occupies a special place, alongside the eyes and eyelashes, as a trifecta that determines one’s beauty. Across the Middle East and the Caucasus, it is a sign of virility and sophistication. If, in the Global South, the monobrow is hot, in the colder climes of the US and Europe, it’s clearly not.

Reverse Joy (Muharram)

Reverse Joy (Muharram) looks at the perpetual protest movement at the heart of the Shi’a commemoration of Muharram, one of the holiest months of the calendar, for its radical reconsideration of history and justice.

Inserting oneself, flesh and faith, into the events that transpired 13 centuries ago; the collapse of traditional understandings of time; the reversal of roles of men and women; and joy through mourning all demand an equally elastic and muscular understanding of the sacred and the profane that is the down payment towards any meaningful social change.

Reverse Joy

Throughout their oeuvre, Slavs and Tatars often use the term ‘metaphysical splits’ to refer to the combination or collision of two mutually exclusive or antithetical ideologies, registers, concepts within one page or space. No work perhaps better captures this idea of coincidentia oppositorum than Reverse Joy. Through the very simple gesture of a red pigment, the fountain brings together two ends of the spectrum: the innocent with the cynical, the naïve with the violent, through a single color red, for some a festive symbol recalling compote or kool aid, and for others the trace of blood, of martyrdom.

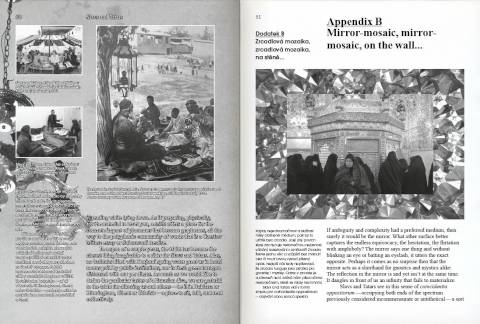

Resist Resisting God

The geometric patterns, upon which the mirror mosaics are based, arrived with the Arab invasions of Persia which introduced Islam in the seventh century. Wood or ceramic was often the Arab medium of choice. The Persians, always keen to distinguish themselves from their Arab neighbours, used mirrors as a bevelled, bling-bling option.

Slavs and Tatars are particularly interested in the revolutionary potential of certain crafts. In the case of Iran, the mirror mosaic best exemplifies the complexity behind the Islamic Republic’s particular brand of anti-imperial imperialism. Much like the Soviets exported agit-prop and socialist realism globally, Iran exports this craft as the aesthetic embodiment of its own ideology to Shi’ite mosques and shrines throughout the region such as the Zeynab Shrine in Damascus.

Hip to be Square

A Polish flag laid over an EP of Huey Lewis’ 1980s hit ‘Hip to Be Square’ and a Kazimir Malevich signature (in decidedly Polish orthography) celebrate the cliché of the plodding Pole by redeeming the methodical, slow-burn nature of the Solidarność strike movement. The seemingly saccharine and innocuous pop song is reinvested with the radicalism of the normal and unsexy, the ‘square’ in English slang, as a successful case study and precedent for other movements of civil disobedience.

In this cycle, the artists look to syncretism – the combination or amalgamation of distinct beliefs, religions, images, languages, or politics – as a third way between the two major geopolitical heavyweights of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: communism and political Islam. Hybrid genealogies are told from the perspective of the region’s fruits: from the persimmon to the mulberry, from the melon to the pomegranate. The history of the region’s flora moves beyond the anthropomorphic focus on historical personages of a region.

Holy Bukhara

A moving example of the syncretism – be it linguistic, religious, or ideological – found in Central Asia, Holy Bukhara is an homage to the Jews of Central Asia, aka Bukharan Jews, whose language, Boxori, provides an unlikely collision of Persian dialect with Hebrew script. Revising the epithet of Central Asia’s holiest city, ‘Bukhara yeh Sharif’ (meaning Holy Bukhara), with one letter, the work celebrates the language as much as the city’s pluralist approach to faith.

Never Give Up The Fruit

Never Give Up The Fruit explores the triangulation of identity against not only the twin ideological poles of communism and political Islam but also the ethnic tensions of Uighurs and Han Chinese. According to legend, the Qianlong Emperor specifically asked that the religious and political leader Afaq Khoja’s granddaughter – known as Xian Fe to the Hans or Iparxan to the Uighurs – be taken alive after Xinjiang was conquered. Her beauty was so renowned that she is said to have been transported back to Beijing in a carriage with felt-lined wheels to ease the long journey. The Uighurs see in Iparxan a symbol of resistance thanks to her alleged refusal to submit to the Emperor’s desires. The Emperor went to great lengths to please her, building a scale replica of Kashgar’s bazaar outside her window to make her feel less homesick, having the famous Hami melons of her homeland delivered, and even allegedly providing her with baths of sheep’s milk. None of this sufficed, nearly driving the Emperor mad and convincing his mother to assassinate his unyielding mistress. Alas, the Han narrative is more mundane, seeing Xian Fe as one of many concubines; in their version of the story, neither her fragrance nor her beauty was enough to save her from the Emperor’s entreaties.

The only part of Central Asia historically under Chinese (as opposed to Russian) rule, the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region is home to the majority of Uighurs and spans 1.6 million square kilometres – roughly equivalent to the surface area of Germany, Spain, and Turkey combined. If, for the West, Islam comes from the East, and the East is often adopted as a shorthand for Islam, the religion of Muhammad comes from the West for the Chinese. Not only does Xinjiang sit just inside Slavs and Tatars’ geographic remit on this side of the Great Wall of China, the province itself is the site of a face-off between the two major geopolitical narratives of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – communism and political Islam, respectively. And crucially, almost without any trace of mediation by the West.

Xinjiang is China’s most resource-rich province, with the world’s largest oil and natural gas reserves; it also has the misfortune of having the lowest population density amongst all Chinese provinces, the result of which has been a large influx of Han Chinese in recent decades, facilitating an Uighur population drop from 75 % in 1953 to 46 % today. The mutual enmity and tension between the Han and the Uighur – from online forums to the very streets of Hotan – is palpable, and conjures up the case of Israel and Palestine, except on steroids. Sandwiched between Russia and China, Xinjiang was a stage during two World Wars, not to mention two communist revolutions thirty years apart. So Uighurs have had their fair share of geopolitical landmines to navigate, with differing degrees of success. In the 1920s, the Soviet Union provided support by establishing unions and workers’ groups, as well as publishing titles catering to the sizeable percentage of Uighurs living in the neighbouring Kazakh and Uzbek Socialist Republics. The early Soviet policy of ascribing a narodnost or ‘ethnicity’ to each and every distinct group of the exceptionally diverse population was one of many attempts to deal with the legacies of Imperial Russia and its transformation into a Soviet society.

There has been no shortage of recriminations and ugly stereotypes on both sides during the many decades of this unhappy marriage: the Han accuse the Uighurs of being lazy, while the Uighurs claim the Han lack proper hygiene. Historic neighbourhoods are razed in their entirety under the pretext of fortifying faulty old constructions, incensing the Uighurs, whom the Han in turn consider ungrateful. Despite being the largest ethnic group by a substantial margin (until recently, that is), the Uighurs are never given top administrative posts or political appointments, instead often holding ceremonial secondary roles.

Dunjas, Donyas, Dinias

Long-standing Serbo-Turkic enmities make peace in Dunjas, Donyas, and Dinias. The word for the fruit “quince” in Serbian – dunja – is a common name given to women as a symbol of beauty, and happens to be the homonym of the word “world” in Arabic and Turkic: donya.

Fragrant Concubine

Hanging Low

Via the puckered lips of someone who smiles backwards, Hanging Low pays homage to the conflicted relationship to memory, to pluralism, and to joy through mourning. Józef Wittlin’s Mój Lwów (My Lvov) laments the loss of the plural identities, languages, and affinities in a city that was once Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, and German, and warns of memory’s selective, if unstated, agenda. He speaks of the strange mix of the sublime and the street urchin, of wisdom and cretinism, of poetry and the mundane – as a special indefinable taste: bittersweet.

How-less

“You Know of the How / I Know of the How-less” is attributed to Rabia al-Adawwiya, a Muslim saint and Sufi mystic. Considered to be one of the first female Sufis, she is credited with pioneering the notion of Divine Love central to the veneration of God in Sufism.

Long Live The Syncretics

Modeled after the branch of a mulberry tree whose fruits are white or black, Long Live the Syncretics delicately dangles ribbons as a nod to the progressive, syncretic approach to Islam in Central Asia, where Buddhist, Hindu, and pantheist rituals are incorporated into the belief system.

The Dear for the Dear

Before the Before, After the After

A fruit of caricature, of the Other, the watermelon often serves as a racist shorthand for African-Americans in the US; while in Russia it recalls the contested Caucasus and in Europe the countries of origin of the migrant populations, be it Turkey, North Africa or elsewhere. Placed in the two Robert Oerley pots at the entrance to the Vienna's Secession, the watermelons encourage visitors to experience the “Not Moscow Not Mecca” exhibition not just cerebrally, but also sensorially and affectively.

Triangulations

Stalinist policy towards Central Asia – ‘To Moscow Not Mecca’ – aimed at replacing Islam with communism as the chief belief system of the local Muslim population of the Soviet Union. Not Moscow Not Mecca chooses not to choose between the two major narratives of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, that is, revolutionary communism or political Islam. Instead, each of the Triangulation road markers brings together a resolutely secular city with one known for its sacred importance.

The march of alphabets has often accompanied the ascension and fall of empires and religions. In Language Arts, the collective unteases the politics of alphabets: the many fraught, often forgotten yet palpable attempts by nations, cultures and ideologies to ascribe a specific letter to a sound. The book Khhhhhhh (Moravian Gallery, Mousse / 2012) examines, literally, the throat as a space of phonetic and sacred agency via the Hebrew, Russian and Arabic letters for the fricative [kh] while Naughty Nasals looks to the nose, as a ‘site of resistance in the Slavic and Turkic languages’.

False Friends

False Friends

Księgożerstwo (Bibliophagy)

Sculpture by Olga Micińska. Part of the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw’s Primary Forms educational program, Księgożerstwo is a stamp and ex-libris challenging adolescents to consider which texts they consider canonical and why.

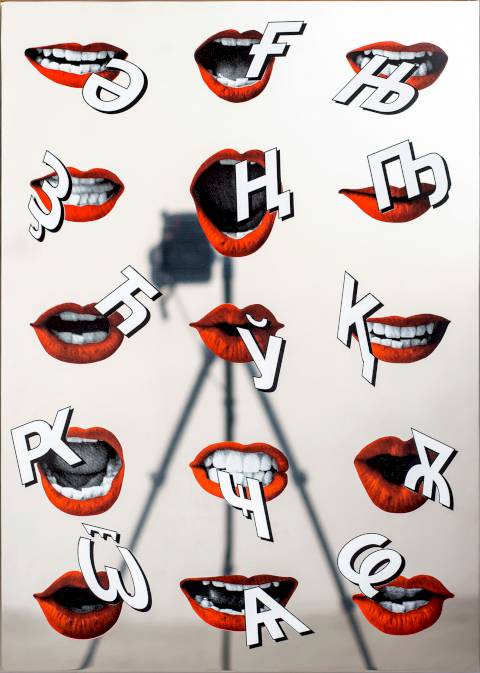

Qatalogue

A mouth emits Cyrillic letters which failed to take hold in various languages, approximations of sounds which did not exist previously in Russian or other slavic languages.

Cyril

Ҹ

Deepthroat Dipthongs have nothing

on you, Jamal, or as our Albanian Apollinarians

say, Xhemal. The Americans called you

the jump /dz/ for one

OlaҸuWon

Hakeem the Dream

No oldies but goodies Kareem

Abdul Ҹabbar who ҹuggled to the rear

empires under Ҹahangir

Қ

The Qit Qat Qlub

headlines the Ka

with a descender

The Qabaret

of your thighs,

The Qutb

of your beloved shuns the Qatalogue

of your lies

Њ

Rudaki wrote about the wine

Hafez and Saadi the divine

but only your seedless

Grapes the gift of caprice

the whine of so

many yes-ño

да нет

jeins

shouldering the

velars of volcanic tides

Ҩ

We are born oui

people and non! people

Ҩui the people fear not

Amiran nor his

Lean and mean

Promethean phonemes

So many echoes in

Noses half Abkhaz

Half aquiline

Jęzzers Język

Jęzzers język celebrates the nasal phonemes specific to the Polish language through a retro exclamation: Yowzers! Unlike most other Slavic languages, the Polish language has prominent nasal phonemes – ‘ą’ and ‘ę’. These letters have provided an unlikely source of self-determination and resistance in the face of pan-Slavism, Russian imperialism, amid a panoply of perceived or real threats.

OdByt

When broken down into its two component syllabes, odbyt (lit. ‘rectum’ in Polish) means ‘from being’. While Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde clearly indicates which orifice the French artist considered a myth of origins, Odbyt argues for the a**hole as the origin of humanity. Meaning ‘from’ in several Slavic languages, the preposition ‘ot’ used to exist in old Church Slavonic as a Cyrillic letter unto itself: ‘Ѿ’.

Larry Nixed, Trachea Trixed

Larry Nixed, Trachea Trixed looks at various attempts to Cyrillicize sounds or phonemes that did not previously exist in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet, one of many attempts to extend or embed Soviet influence, with a decidedly more sensuous, if not sexualized, approach to the traditionally cold, clinical approach of linguistics.

Ezan Çılgıŋŋŋŋŋları

Enforced from 1932 to 1950, the Turkish translation of the traditionally Arabic call to prayer, or ezan, was perhaps the most controversial piece in an elaborate constellation of language reforms in the Republic of Turkey. To begin with, translating Allah to Tanrı problematizes the very central tenet of the faith – the unicity of God (tawhid) – through the use of a pre-Islamic, shamanist term dating to the era of the Mongols and Genghis Khan, meaning ‘the great sky’. Ezan Çılgınları – literally, the ‘call-to-prayer crazies’ – was the term used for those who defied the authorities’ enforcement of the Turkish ezan by climbing minarets and performing the call to prayer in the original Arabic. Despite a rocky ride, the language reforms known as dil devrimi advanced relentlessly...until 1950, when the call to prayer was changed back to Arabic. To this day, many Kemalists see in this reversal the first of many concessions leading to the increased public face of Islam in Turkish society and politics of the past decades.

For the eighth Berlin Biennale, Slavs and Tatars revisited this particular episode through an unwieldy restaging of the ezan. In collaboration with musician Jace Clayton (DJ /rupture), Turkish call to prayer was recorded with Vocaloid™ for an entirely computer-generated, a cappella summons or chant. If once Young Turks, Gökalpists, and other reformists considered the Turkish replacement a way of anchoring the young republic to the West, five decades later it seems to have had the exact opposite effect: reactivating a thoroughly different understanding of Turkey’s linguistic and cultural genealogy. If the Ottoman Empire pushed southwards and westwards, then Ezan Çılgıŋŋŋŋŋları pushes east towards Central Asia – not just the Balkans or the Middle East – extending across the steppe, nearer to China than Europe.

The distinct Turkish (as opposed to Arabic) phonetics of the call to prayer sheltered it from potential Islamophobic attacks or protests from residents surrounding its outdoor installation at the Haus am Waldsee. Set on the bucolic slope of grass outside the exhibition space, the lake acts as nature’s own loudspeaker, pushing the call to prayer further outwards. Due to the peculiar tonalities of the language, the Turkish ezan is far more consonant-heavy, especially compared to the more open-vowelled Arabic adhan. While the recognizability of Allāhu akbar makes it a vocal lightning rod, the same could not be said of Taŋrı uludur.

Listen to audio file here

The Naughty Nasals

The Naughty Nasals identify the nose as an unlikely site of sonorous resistance to the instrumentalization of scripts, or alphabets. The ‘Ѫѫ’ (wielki jus) and ‘Ѧѧ’ (mały jus) invoke nasal sounds that have disappeared from most Slavic languages but remain as ‘ą’ and ‘ę’ in contemporary Polish. As mobile confessionals, they are a testament to one of the lesser known, aborted attempts to Cyrillicize the Polish language in the nineteenth century. Despite the often very clinical approach of linguistics, the various organs of language represent a distinct erogenous: be it the teeth, lips, mouth, tongue, neck, ears or nose. The sequel to the artists' publication Khhhhhhh, the similarly title book The Naughty Nasals (Galeria Arsenal, 2014) explores the nose as a rupture from the norm of language poltiics across the Polish and Turkic languages.

Swinging Septum

Long eclipsed by the mouth as a source of libidinal linguistics, Swinging Septum restores the nose as an equally discursive and desirous organ of language. A flat silhouette nose sways from left to right, evocative of the facial acrobatics the septum must perform to reach the sonorous heights of /ɛ̃/ or /ŋ/ to name but a few.

Nose Twister

Turkey today has only one measly alphabet. The Turkish language put the thorny issue of alphabet politics to rest in little over eight decades: the massive alphabet reform launched in 1928 by the Türk Dil Kurumu (Turkish Language Institute) stands uncontested to this day. Even a reactionary Salafist in Turkey might think twice about bringing back the Arabic script: the Romanization project in Turkey was, as Geoffrey Lewis put it best, ‘a catastrophic success’.

Among the letters that didn’t quite make it from the sinking ship of Ottoman Turkish to the newly Romanized shores was the 28th letter of the alphabet, a little twitch at the back of the nose, the ڭ or Kêf-î Nûni. Until 1928, the Turks had two different <n> sounds: the conventional ن (n), the one you’d be happy to introduce to the parents, as in نهایت, ‘never’, or ‘nomenklatura’; then there’s the ڭ, a more peculiar, eccentric type of n, pronounced in the depths of the nose, as the <ng> in ‘sing’. The very pronunciation of <ng> has all the first-degree Oriental trappings of a snake-charmer, or more aptly, a gong. For good reason: <ng> figures among the most common Chinese surnames, with an extensive Wikipedia entry dedicated to ‘Notable people with the surname Ng’ to boot. In Turkey, words that used to have the <ng> have progressively whitewashed it out of existence, like blacklisted party members from an official photo – an unwanted reminder of phonetic, linguistic, if not national disruption. Dengiz became deniz (sea), tangri became tanri (all-encompassing sky).

Reverse Joy (Kha)

Throughout their oeuvre, Slavs and Tatars often use the term ‘metaphysical splits’ to refer to the combination or collision of two mutually exclusive or antithetical ideologies, registers, concepts within one page or space. No work perhaps better captures this idea of coincidentia oppositorum than Reverse Joy. Through the very simple gesture of a red pigment, the fountain brings together two ends of the spectrum: the innocent with the cynical, the naïve with the violent, through a single color red, for some a festive symbol recalling compote or kool aid, and for others the trace of blood, of martyrdom. Here, three iterations – in Hebrew, Cyrillic and Arabic alphabets – of the phoneme [kh] dance ceremoniously around the red fountain.

Rahlé for Richard

Rahlé for Richard uses the form of the stand for holy books (or rahlé), a leitmotif in Slavs and Tatars’ work, given the importance of books and language in their practice. Here, the tongue sticks out, a gesture equally of interjection and emphasis, as in a shout or cry. Rahle for Richard suggests the transition from oral to print cultures: whether it’s the relatively late arrival of Islam to print, despite having access for several centuries, or the hesitation of the Orthodox faith to adopt print. The homage to Richard Artschwager is manifold: Artschwager’s consistent use of surface as something with depth, beguiling, uncannily thick. His veneers belie something else, be they pianos or other. In S&T, the artists turn to humor, pop, witticisms, and rumours with a similar understanding of surface, of the very thick first degree, both revealing and obscuring subsequent layers of meaning.

Love Letters

Ten tufted carpets, each equal in dimension, investigate language as a source of political, metaphysical, even sexual emancipation. By revising original drawings by Vladimir Mayakovsky, Love Letters address the very charged if slippery issue of language through one of its best-known, if conflicted, champions. The tongue’s yin and yang, its bipolar disorder – as a source of man’s greatest achievements and yet a cause of his tragic failures – finds its appropriate poster-boy in the figure of Mayakovsky, whose Futurist experiments with language and embrace of the nascent Bolshevik regime resulted in some of the most important works of avant-garde art and literature. Yet his own instrumentalization of language for the purposes of the revolution eventually led to his own disillusionment and suicide, a watershed moment widely believed to mark the beginning of Stalin’s terror.

Through caricature, the carpets depict the wrenching experience of having a foreign alphabet imposed on one’s native tongue and the linguistic acrobatics required to negotiate such change. In particular, the carpets tell two parallel stories: that of the Bolsheviks’ forced Latinization and later Cyrillicization of the largely Turkic peoples of the Russian Empire, and the 1928 language revolution of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – Turkey’s first president – in which the Turkish language was converted from Arabic to Latin script. The casualties of these linguistic takeovers – lost letters and mistranslations – are given center stage here as a testament to the trauma of modernization.

Qit Qat Qa

The phoneme [gh], corresponding to the Arabic letter ‘qaf’, is pronounced even further back in the throat than [kh], the subject of Slavs and Tatars’ publication Khhhhhhh. Often transliterated in the Latin alphabet as ‘q’ or ‘k’ (in Qur’an or Koran, for example), the Soviet attempt to Cyrillicize ‘qaf’ led to drafting a wholly new grapheme, a ‘ka’ with a descender, which is still in use in Tajikistan but abandoned in other Central Asian countries. Beyond a mere letter, qaf is the Sufi name of a cosmic mountain, home to the mythical bird the simorgh – a precursor to the жар-птица (zhar ptitsa, meaning firebird) found in Slavic fairy tales, the phoenix, or, more recently, Banshee from the motion picture Avatar (2009).

Madame MMMorphologie

Madame MMMorphologie continues Slavs and Tatars’ interest in language as a form of affective if not affectionate emancipation. Winking at passersby, the tome also speaks to the collective’s bibliophilia: an anthropomorphic edition of Molla Nasreddin, the legendary 20th century Azerbaijani satire the artists translated, bears witness to the alphabet politics of the Turkic languages under Soviet rule.

Other People’s Prepositions

A preposition is a word explaining a relation to another word. And perhaps no preposition is as central to Slavs and Tatars’ specific cosmology as the word ‘from,’ given the artists' interest in historiography, research, and genealogy. The preposition ‘from’ also indulges an anti-modernist perspective – facing the past but moving forward towards the present, like Molla Nasreddin, the 13th century Sufi wise-man-cum-fool, often depicted riding backwards on his donkey.

Literally ‘from’ in several Slavic languages, the preposition Ѿ or ot used to exist in old Church Slavonic as a Cyrillic letter unto itself. OPP tries to restore this ligaturial luxury – a combination of the Greek Omega and Theta – through a meditation on the preposition’s more carnivalesque tenor.

Tongue Twist Her

A pole often found in nightclubs or sex bars has traded in the topless dancer for something no less racy: a giant, fleshy tongue. The alphabet changes in many parts of the former-Soviet, largely Turkic speaking world from Arabic script to Latin to Cyrillic back to Latin in 60-odd years has made whole populations immigrants within their own language. Tongue Twist Her shows not peoples or nations that are liberated, but the dizzying and devastating swings – in this case lingual – of phonemes, graphemes, and organs.

ωXXX

Meaning ‘oops’ in Greek, ωXXX (okh) is an example of linguistic and cultural transmission, with the great omega’s sassy side highlighted by the proximity of a gang of x’s for a particularly attractive alliterative stuttering. Not by coincidence, the ‘x’ is a Cyrillic and Greek letter for Slavs and Tatars’ signature guttural phoneme, [kh], and subject of their publication Khhhhhhh.

Öööps

One of the principal arguments for changing the Turkish script from Arabic to Latin – the inability of the Arabic alphabet to accommodate the full range of vowels in Turkish, namely the ‘ü’ and ‘ö’ – here serves as both sophisticated as well as lowbrow, slapstick humour. This lengthened version of the word ‘kiss’ in Turkish presents the vowel change as equal parts typo/ editing error and modernist mini-miracle – if not metaphysical mishap.

Mother Tongues and Father Throats

A diagram showing letters of the Arabic alphabet and the corresponding part of the mouth used to pronounce these letters, Mother Tongues and Father Throats turns to the throat as a source of mystical language – as opposed to the the tongue's more profane, transactional role. Here, the artists have added the letters for guttural phonemes [gh] and [kh] in Cyrillic and Hebrew as a nod to these letters' importance across disparate fields such as Russian futurism, Kabbalist gematria, and Sufi exegesis.

Kh Giveth and Kh Taketh Away

Kh Giveth and Kh Taketh Away further mine the phoneme [kh] as a source of mystical if not fricative potential. The mirrors champion the throat and its ability to constrict as opposed to facilitate the passage of air in this decidedly anti-imperialist phoneme.

Mirrors for Princes refers to a medieval and renaissance genre of advice literature in both Islamic and Christian cultures that counselled rulers on matters of statecraft, the body politic, and good governance. Mirrors for princes (specula principum or Fürstenspiegel) represented an early form of secular scholarship that raised the level of statecraft to that of religious jurisprudence or theology. For the artists, aside from producing and foreshadowing a ‘care of the self’ that was instrumental in western modernity, mirrors for princes is a form in which critique is presented as a form of gift-giving or hospitality.

The Contest of the Fruits

A 19th century Uyghur poem is staged as a proto-Turkic rap battle between 13 fruits in this seven minute animation.

Aşbildung

Linking spiritual and intellectual nourishment, Slavs and Tatars ask us to consider mind and stomach as one entity, a literary, imaginative space added to a no less discursive if more commercial operation. For the 2021 Public Commission of Osnabrück, the artists collaborated with a local döner kebab shop, adding a literary element to the usual transactional one of fast food. Placemats featuring excerpts from Kutadgu Bilig, the 11th century epic Turkic poem, dürüm wrappers with the artists Kitab Kebab and a public performance program are among the artist interventions within the venue.

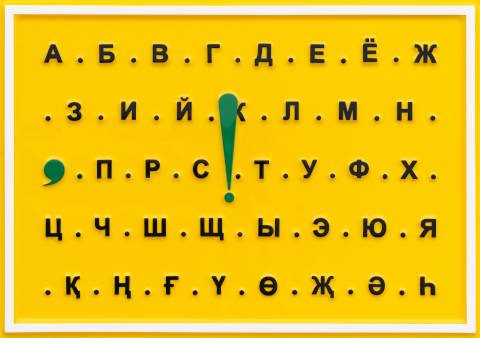

The Alphabet (Uyghur kril yéziqi)

The Alphabet revisits Marcel Broodthaers’ Poèmes industriels, replacing the Latin alphabet with an Cyrilized Uyghur one. The original exclamation of ‘OK!’ survives unscathed, despite the transmogrification from the secularized world of Latin.

Who are you?

The Arabic word هو (pronounced ‘who’) is often used by mystics in Islam to evoke the Divine. In particular it is chanted by Sufis rituals incarnations (zikr) like a mantra. However, the word هو also literally means ‘he’, using a gendered masculine form to express God. Who are you? poses the existential question as one not only between secular and holy but also between the various normative gender variations of the former and latter.

Saturday

An act or document freeing a slave, several manumissio (written on left and right sides of the work, in Hebrew and Greek) have been found in Crimea. According to the Hebrew bible, slaves were to be freed in the seventh year, known as the Saturday or Shabbat year, after six years of labour, regardless of their origin, performance, or profile. Given the struggle of Jews throughout history, from the Exodus to pogroms to diaspora, this was a rather progressive if not generous approach to a contentious issue, especially when compared with that of their Christian and Muslim contemporaries.

Alphabet Abdal

Though considered to be the sacred language of Islam, the Arabic language and alphabet is equally the language of Middle Eastern Christians. Featuring an exodus, Alphabet Abdal commemorates the endangered Levantine, Hijazi origins of Christianity, and, with it, the heritage and language that expresses these traditions. The text reads: ‘Jesus, son of Mary, He is Love’.

Stongue

Elongated and straightened, a heart morphing into a tongue attempts to speak but shows sincerity to be a constraint as much as an opportunity.

AÂ AÂ AÂ UR

An oversized set of prayer beads, sprouting from the ground, AÂ AÂ AÂ UR addresses the balance between seclusion and society, spirit and state, echoes of which we continue to find in the US, Europe and the Middle East today. The beads’ scale and momentum, launched from below the surface, invite a quiet playfulness, in particular with regards to a subject matter often brushed under the proverbial rug: the potential for a progressive agency in faith.

Bazm u Razm

The glass combs of Bazm u Razm swing between the afro-combs of hip hop culture and talismanic forms found around Uighur tombs in Xinjiang, western China, where they are used as family designations or seals. The grooming or taming of hair has been tied to that of civilization and order for some time, with the curly, frizzy, unruly often construed as a social, sexual, or psychological menace. In Bazm u Razm, literally ‘banquet or battle’, the combs are portrayed as markers of order and violence: the Turkic peoples extending from Mongolia all the way to the Balkans were renowned for their skills as warriors as well as hosts.

Lektor

The multichannel audio work Lektor (speculum linguarum) from 2014 contains text drawn from the eleventh-century Turkic mirrors for princes Kutadgu Bilig (Wisdom of Royal Glory), read in its original Uighur with several voice-overs. The selection of translations (German, Turkish, Polish, Arabic, Scots Gaelic, Aboriginal Jagera, Flemish, Danish, Spanish, and Persian) for the voiceover or ‘dub’ traces the exhibition history of the piece through the languages of venues. Used for films in Poland and Russia, and elsewhere only for news segments, the simultaneous playback of a voice-over translation, a technique known also as Gavrilov translation, makes for a disruptive experience, touching on issues of legibility, authenticity, and language as a form of hospitality.

Written in the eleventh century in Kashgar, in what is known today as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in western China, Kutadgu Bilig is a cornerstone of Turkic literature. The importance of the work is difficult to overstate: it is to Turkic languages what Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh is to Persian, Beowulf to English, or Nibelungen to German. In rhymed couplets (masnavi), four main characters personify four abstract principles: Justice, Fortune, Intellect, and Contentment. Their debates serve as a rare example of Socratic dialogue in a Muslim tradition known for its theological emphasis on the One. A central discussion takes place between a Sufi dervish and a vizier to the king, whose names are, respectively, Wide Awake and Highly Praised – addressing the balance between seclusion and society, spirit and state, whose contours resonate today as much as a millenium ago.

The Squares and Circurls of Justice

Turbans, some designating students, others elders, greet visitors upon entry. The act of removing headwear or disrobing, like that of coats or outerwear, implies entry to an intimate if not sacred space, as opposed to the more secular public space of a cultural institution.

Hirsute Happily with Hairless

Zulf

A brunette and blond rahlé (or book-stand used for holy books) offers another take on the seduction of texts and exegesis.

Irokez